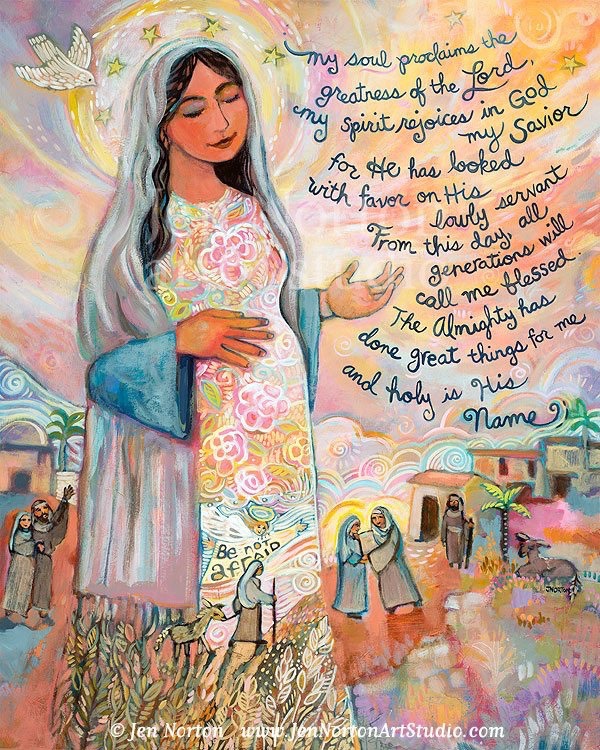

Continuing to offer us selections from Luke’s Gospel, this year, the Narrative Lectionary proposes a passage for this coming Sunday containing three distinct events. First, Jesus is engaged by some Pharisees while he “was going through the grainfields” (Luke 6:1–5). Next, after he “entered a synagogue and taught”, he healed “a man whose right hand was withered” (6:6–11). Then, after spending a night on a mountain in prayer, Jesus “called his disciples and chose twelve of them, whom he also named apostles” (6:12–16).

Each section contain words which presage significant elements in the time when Jesus was active. The question of the Pharisees, “why are you doing what is not lawful on the sabbath?” (6:2), is later thrown back on the Pharisees and scribes by Jesus in another healing scene (14:3), asked in a way that strongly suggests that what Jesus was doing was, indeed, in accordance with the provisions of Torah.

Still later, the assembly of “the elders of the people, both chief priests and scribes” accuse Jesus of three breaches of law, as they tell Pilate that he has been “perverting our nation, forbidding us to pay taxes to the emperor, and saying that he himself is the Messiah, a king” (23:2). Three times, Pilate refuses to accept these charges as proven: “I find no basis for an accusation against this man” (23:4); then “I have examined him in your presence and have not found this man guilty of any of your charges against him [and] neither has Herod … he has done nothing to deserve death” (23:14–15); and finally “I have found in him no ground for the sentence of death” (23:22).

We know, however, that the Pilate created by the writers of the Gospels eventually succumbs to the cries of the crowd; Luke reports that “Pilate gave his verdict that their demand should be granted … he handed Jesus over as they wished” (23:24–25). It’s almost like a counter-Trumpian scenario: we know he is in innocent, but we will backpedal and condemn him anyway. (With Trump, we know he is guilty, but the courts backpedal and dismiss the charges.)

The accusation of being “lawless”—a serious matter for a Torah-abiding Jew, such as Jesus (see my blog on Luke 4)—rears its head again in the sequel to Luke’s Gospel narrative, when one of the followers of Jesus who have all been faithful in their participation in the Temple rituals (Luke 24:53; Acts 2:46; 3:1; 5:42) is accused directly in words reminiscent of those brought against Jesus: “this man never stops saying things against this holy place and the law; for we have heard him say that this Jesus of Nazareth will destroy this place and will change the customs that Moses handed on to us” (6:13–14). Stephen, of course, goes to his death, just as Jesus did.

Following this pattern, later in Acts a crowd of “Jews from Asia” seized Paul in the Jerusalem Temple, who claim “this is the man who is teaching everyone everywhere against our people, our law, and this place; more than that, he has actually brought Greeks into the temple and has defiled this holy place” (Acts 21:28). Paul is subsequently brought before Roman authorities. The tribune in Caesarea referred him to Governor Felix, noting that “he was accused concerning questions of their law, but was charged with nothing deserving death or imprisonment” (23:29).

In Paul’s defence, he affirms “I worship the God of our ancestors, believing everything laid down according to the law or written in the prophets” (24:14), just as in Jerusalem he had maintained “I am a Jew, born in Tarsus in Cilicia, but brought up in this city at the feet of Gamaliel, educated strictly according to our ancestral law, being zealous for God” (22:3). Left in prison for two years, Paul is later brought before Governor Porcius Festus, who travels to Jerusalem to receive a report against Paul from “the chief priests and the leaders of the Jews” (25:2; see earlier 22:30), the same group (albeit of a later generation) which had charged Stephen (6:12; 7:1) and, before him, Jesus (Luke 22:66; 23:13–18).

Festus involves Agrippa and his consort Berenice; between the three of them they agree, “this man is doing nothing to deserve death or imprisonment” (26:31). Yet in a perverse result (once again seemingly counter-Trumpian), Agrippa notes that “this man could have been set free if he had not appealed to the emperor” (26:32).

So there is a strong thread running through the two-volume narrative which Luke has created: accused of breaking the law, Jesus and the leading figures in the movement initiated by him are steadfastly deemed to have been Torah-observant. So the Gospel reading for this Sunday sounds an important theme which receives extensive apologetic treatment in Luke’s narrative.

The theme is developed in the first two sections of the designated passage, where specific instances of “breaking the law” are narrated. In both stories, Jesus is accused of “working on the sabbath”: something that was prohibited in The Ten Words, in the command relating to the seventh day, when “you shall not do any work” (Exod 20:9–10; Duet 5:13–14; see also Lev 23:3; Jer 17:24).

However, a blanket prohibition like this needed some nuancing. What about “working” to prepare food and drink on the sabbath? What about “working” to attend to the animals kept on the farm on the sabbath? What about “working” to save a life on the sabbath? Commonsense would indicate that certain exemptions were necessary.

Of course, ongoing rabbinic discussion did canvass precisely that: just what were the acceptable exceptions and what were not. We have access to these originally oral discussions through the written text of the Mishnah, a third century CE collection of rabbinic discussions of Torah. In the second Division, Moed, “festivals” are considered, and the first of these is Shabbat, discussing who is “liable” and who is “exempt” in a whole range of situations. It is this written discussion which best informs the stories told in in Luke 6—even given that Luke wrote in the late C1st, while the Mishnah is an early C3rd document (which lays claim to providing accounts of earlier oral discussions).

In terms of the first issue—plucking grains of head on the sabbath—the debate is conducted with reference to relevant scripture texts. The primary text, as,we have noted, is “do no work on the sabbath”. However, Hebrew Scripture does contain indications of ways to moderate that commandment: in particular, the plucking of grain to assuage hunger was permitted (Deut 23:25).

When the disciples plucked the grain on the Sabbath, technically they were harvesting food and then processing it (rubbing it in their hands to create a floury substance). Now one part of scripture seems absolute on this matter: “Six days you shall work, but on the seventh day you shall rest; even in plowing time and in harvest time you shall rest” (Exod 34:21). The expectation was that people would prepare for Sabbath meals before the time of rest began on sundown on Friday (see Exod 16:23–26).

However, Jesus—like the Pharisees—does not simply let things rest there. It is not a matter of “this is what the text says; that settles it”. No; Jesus—like the Pharisees—makes use of the time-honoured debating technique of midrash to offer a different way of considering the issue, to propose a different line of interpretation.

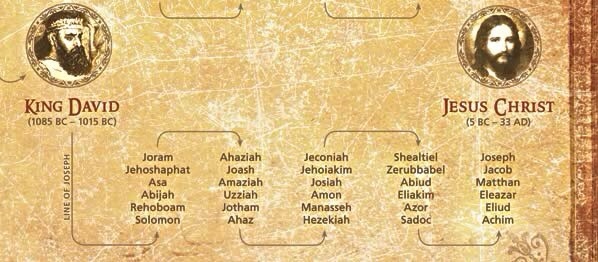

We should note that Jesus does not criticise the law as such, but rather the Pharisees’ interpretation of it. He offers a different interpretation, drawing on another part of scripture—a story involving David from the narrative section of Hebrew Bible (1 Sam 21). In doing this, Jesus demonstrates the midrash technique so often used by Pharisees and, later, rabbis. Jesus uses this story to demonstrate that in some instances, circumstances can override the foundational law.

David breached the law by requesting, and receiving, from the priest Ahimelech some of the “holy bread” which was reserved for use only in the sanctuary. (In telling this story, Luke eliminates an error made in the early version found in Mark, where the high priest was mis-identified as Abiathar; see Luke 6:4 and cf. Mark 2:26.) The conclusion is an application of analogy (another method used by a Pharisees and rabbis): just as David was permitted to eat what was not lawful because of his great hunger, so Jesus was permitted to heal on the day when this normally was prohibited. That is, the circumstances justified the action.

We should note that Jesus, here, does not speak against the commandment itself (do not work on the sabbath). Rather, he shows how the application of a fundamental principle can be modified if there are circumstances that justify this. And that justification is provided by drawing from elsewhere in scripture to support the exemption.

We know from the later rabbinic literature that even amongst themselves, the Pharisees rarely agreed on the interpretation of any Law — many alternative interpretations exist in Mishnah, Tosefta, and Talmuds, for each of the commandments being discussed. In particular the Rabbinic schools of Hillel and Shammai were famous for their disagreements; far too often they offered different interpretations of the same law.

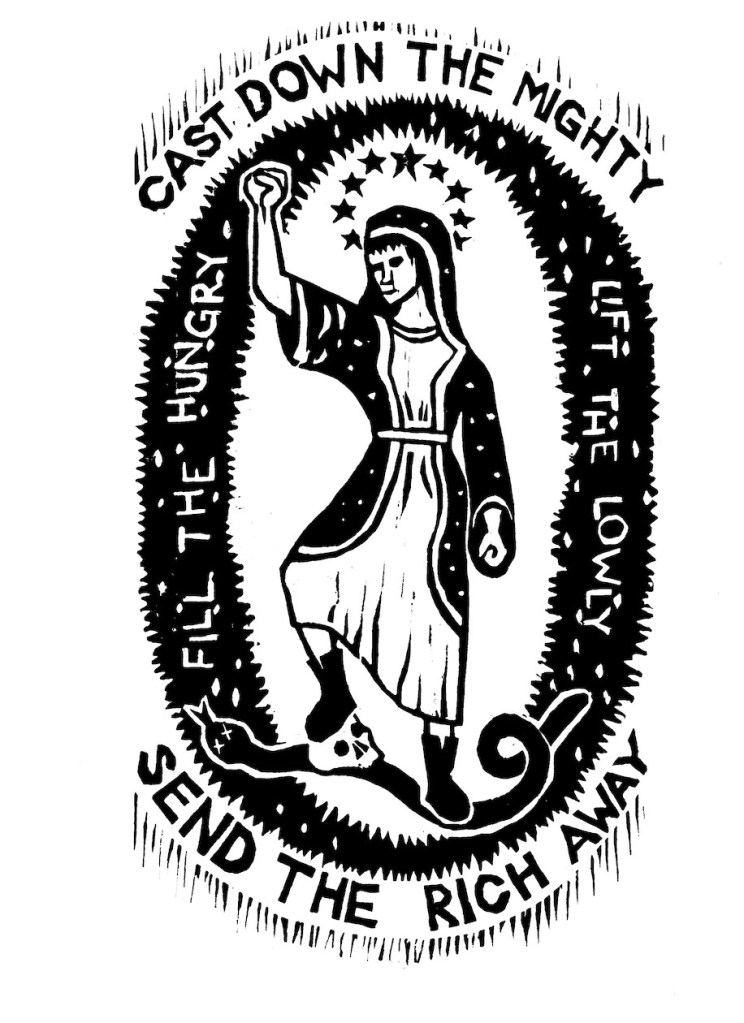

It’s a common Christian misconception that Jesus’ interpretations of the law are always new and very different from any Jewish interpretation. This is simply not the case. In this debate with some Pharisees, Jesus draws a conclusion that is often seen to be revolutionary. However, a number of rabbis, using Hebrew bible parallels (cf. Exodus 23:12; Deuteronomy 5:14) also stressed that the sabbath was for people as well as for their refreshment after labouring. One saying found in the Rabbinic writings (Mekilta on Exod, 31:14; b. Yoma 85b) declares that “the sabbath is handed over to you, not you to it”.

The principle can then be applied to the scene that follows, when in an unidentified synagogue on “another sabbath”, Jesus encounters the man with a withered hand. He heals him, again infuriating the scribes and the Pharisees who were watching on, waiting to trap him (Luke 6:6–11). After healing the man, Jesus quotes a principle—the priority of not doing harm, of saving life—demonstrating that human need can override the foundational principle of “no work on the sabbath” (6:9). Torah always needs to be explored and interpreted. Jesus does just that.