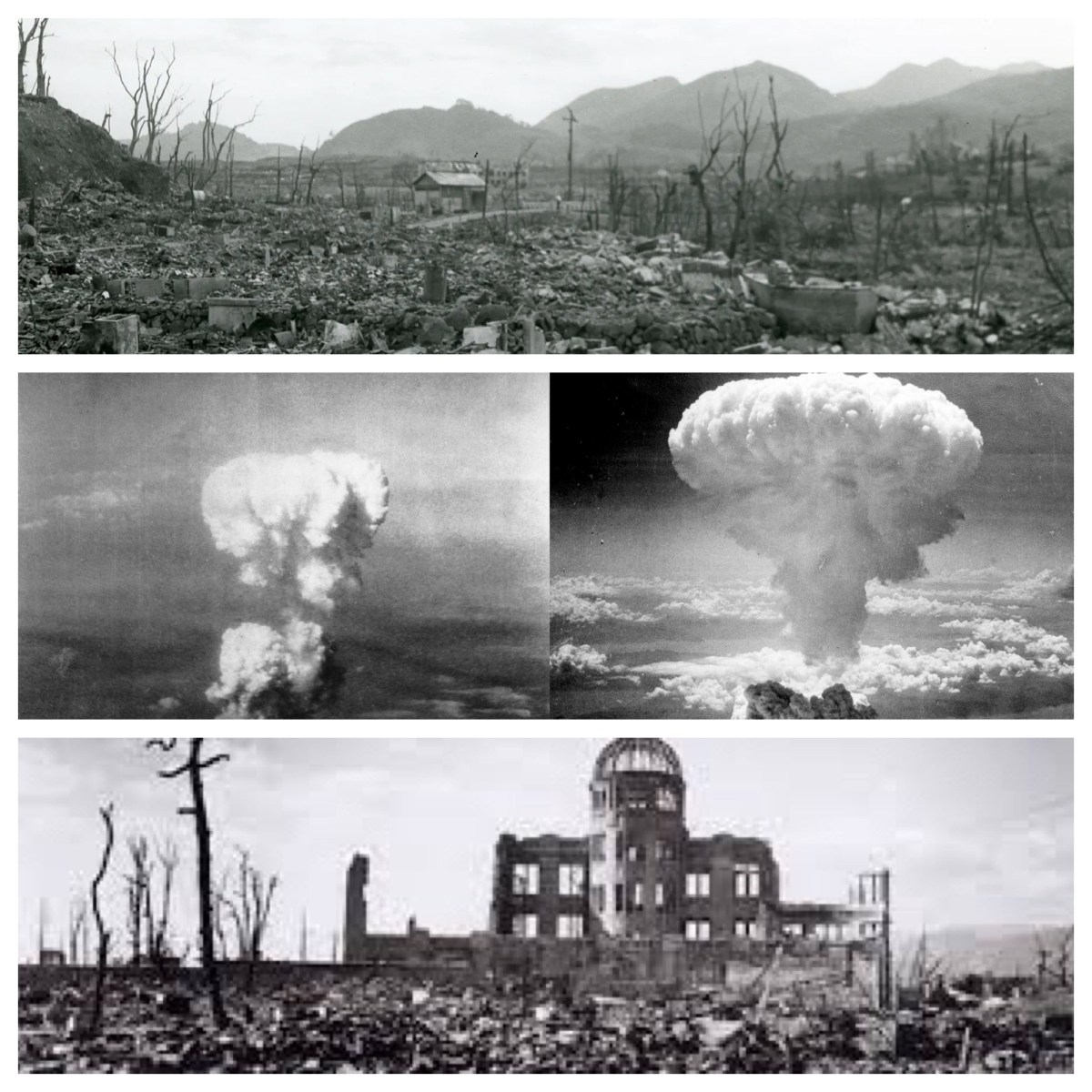

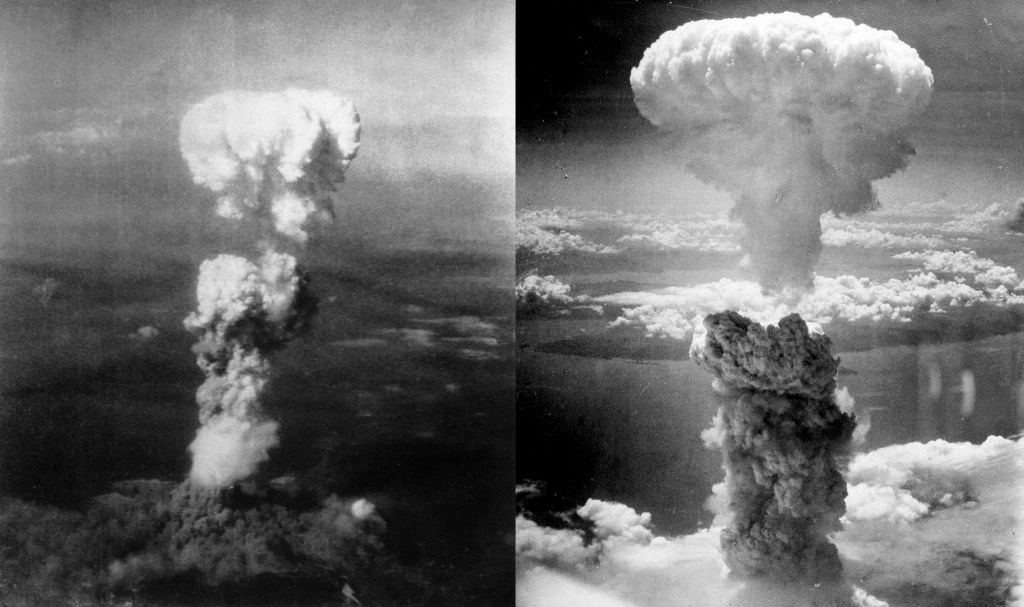

On 6 August 1945, at 8:15 am, a nuclear weapon which had been given the ironic name “Little Boy” was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The bomb was dropped from an American B-29 plane, the Enola Gay. A number of military units were located nearby, including the command centre for the defence of all of southern Japan.

Three days later, on 9 August 1945, at 11:01 am, another nuclear weapon was dropped from another American B-29 plane, the Bokscar, onto another Japanese city, Nagasaki.

In the months before August, Tokyo and Yokohama and other cities had been extensively fire-bombed, but no one could have imagined the devastation of the A-bombs. It has been estimated that these two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, on the day and in the weeks immediately following the bombings. There are many other deaths that took place in the years afterwards, as well as many, many accounts of diseases, which have been attributed to the fallout from the nuclear bombs.

These two incidents remain the only use of nuclear weapons in an armed conflict. They come to the fore of our attention in August each year, as the anniversary rolls around. This year, however, it may well be more focussed, because,of the recent release of the movie Oppenheimer, which tells the story of Robert Oppenheimer, who was the driving intellectual force behind the development of the technology that enabled nuclear power to be exploded in such a destructive way.

Also involved in that process was Mark Oliphant, an Australian scientist, who some commentators believe was the person that guided Oppenheimer from his theoretical scientific pursuits into this applied field of using physics for human warfare. See

(I haven’t seen the movie, so am making no comment on that; I have read some reviews which suggest that it is well made and worth watching.)

I have reflected on the devastating and enduring impacts of these two bombings at

This year, in remembering these two bombings and the subsequent damage caused by them both, I have explored some online resources relating to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the ongoing impacts of those two terrible bombings.

On one online page, creative writer Marie Neil writes about the personal impact of warfare: “Increasingly, we realise war is not even about soldiers – the greatest casualties are always civilians – just like the atomic blasts all those decades ago. Returned men and women, damaged beyond recognition suffering the extremities of loss and bereavement.

“They do not get over it, or move on, or get closure. Survivors with grievous wounds often chose suicide, others clung to another existence, a shadow of their previous life. There were soldiers who had accidents or illness and died without getting near a battlefield.” It is a never-ending roll of casualties, spread across the world.

In commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the dropping of bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki almost a decade ago, TIME Magazine curated a selection of testimonies from survivors in both cities, recounting their experiences in 1945. It makes for sober reading.

YASUJIRO TANAKA (in Nagasaki)

“I lost hearing in my left ear, probably due to the air blast. More than a decade after the bombing, my mother began to notice glass shards growing out of her skin – debris from the day of the bombing, presumably. My younger sister suffers from chronic muscle cramps to this day, on top of kidney issues that has her on dialysis three times a week. ‘What did I do to the Americans?’ she would often say, ‘Why did they do this to me?’”

SHIGEKO MATSUMOTO (in Nagasaki)

“At 11:02am, the sky turned bright white. My siblings and I were knocked off our feet and violently slammed back into the bomb shelter. We had no idea what had happened. As we sat there shell-shocked and confused, heavily injured burn victims came stumbling into the bomb shelter en masse.

“Their skin had peeled off their bodies and faces and hung limply down on the ground, in ribbons. Their hair was burnt down to a few measly centimeters from the scalp. Many of the victims collapsed as soon as they reached the bomb shelter entrance, forming a massive pile of contorted bodies. The stench and heat were unbearable. My siblings and I were trapped in there for three days.”

FUJIO TORIKOSHI (in Hiroshima)

“I heard my mother’s voice in the distance. ‘Fujio! Fujio!’ I clung to her desperately as she scooped me up in her arms. ‘It burns, mama! It burns!’ I drifted in and out of consciousness for the next few days. My face swelled up so badly that I could not open my eyes. I was treated briefly at an air raid shelter and later at a hospital in Hatsukaichi, and was eventually brought home wrapped in bandages all over my body.

“I was unconscious for the next few days, fighting a high fever. I finally woke up to a stream of light filtering in through the bandages over my eyes and my mother sitting beside me, playing a lullaby on her harmonica. I was told that I had until about age 20 to live.

“Yet here I am seven decades later, aged 86. All I want to do is forget, but the prominent keloid scar on my neck is a daily reminder of the atomic bomb. We cannot continue to sacrifice precious lives to warfare. All I can do is pray – earnestly, relentlessly – for world peace.”

INOSUKE HAYASAKI (in Nagasaki)

“The injured were sprawled out over the railroad tracks, scorched and black. When I walked by, they moaned in agony. ‘Water… water…’

I heard a man in passing announce that giving water to the burn victims would kill them. I was torn. I knew that these people had hours, if not minutes, to live. These burn victims – they were no longer of this world.

‘Water… water…’

“I decided to look for a water source. Luckily, I found a futon nearby engulfed in flames. I tore a piece of it off, dipped it in the rice paddy nearby, and wrang it over the burn victims’ mouths. There were about 40 of them. I went back and forth, from the rice paddy to the railroad tracks. They drank the muddy water eagerly. Among them was my dear friend Yamada. ‘Yama- da! Yamada!’ I exclaimed, giddy to see a familiar face. I placed my hand on his chest. His skin slid right off, exposing his flesh. I was mortified. ‘Water…’ he murmured. I wrang the water over his mouth. Five minutes later, he was dead.

“In fact, most of the people I tended to were dead. I cannot help but think that I killed those burn victims. What if I hadn’t given them water? Would many of them have lived? I think about this everyday.”

My colleague Chris Walker has written wisely, in reflection on war and the great damage it causes: ‘Let us then be peacemakers following the way of Jesus. Jesus himself rejected the way of the sword. At his arrest he told his disciples to put away their swords. He followed the way of suffering love and did not resort to violence. Even on the cross he cried out, “Father forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing” (Luke 23:34).’ See

For my earlier blog on these bombings, see

See also