In exploring the history of the land and house which Elizabeth and I purchased in Dungog a few years ago, I have already noted the early landholders for this property, and investigated the life of Daniel and Sarah Bruyn and their family after Daniel purchased the land in 1858.

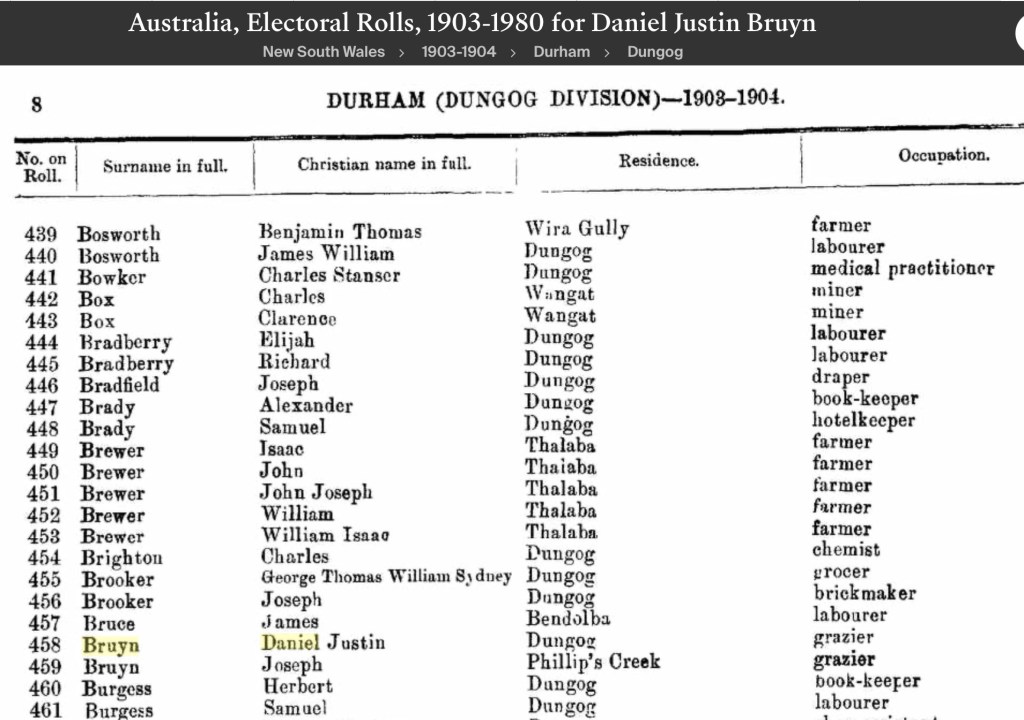

When Daniel died intestate in 1882, all of his property was made over to his son, Daniel Justin Bruyn, whose life has already been canvassed. A few months later, we find that the land he received from his father in Brown St had been purchased by his sister, Ellen Bruyn. This is her story.

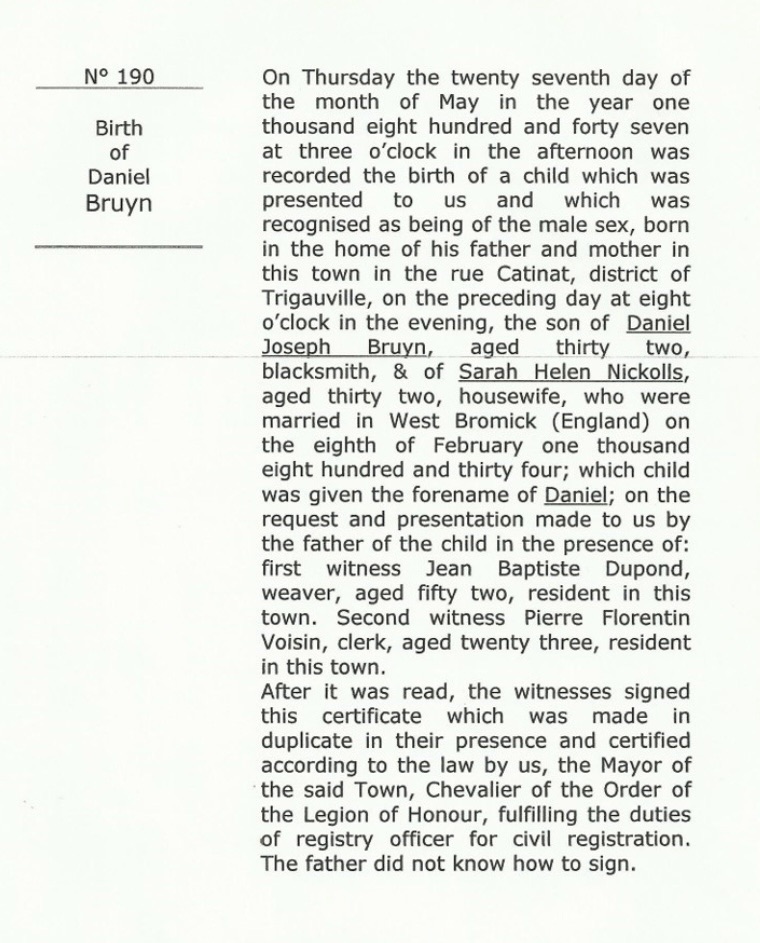

Ellen Esther Bruyn was born in in the later months of 1839 in Smethwick, Metropolitan Borough of Sandwell, West Midlands, England, the second daughter of Daniel Joseph Bruyn, a Blacksmith (1796—1882), born in Roscommon, Ireland, migrated to England, and Sarah Helen Nichols (1807—1882), whom he married on 5 Feb 1837 (to 4 May 1882) in West Bromwich, Staffordshire. Ellen was the fourth child born to Daniel and Sarah; a further three children were born in subsequent years.

The family travelled to France in about 1845, where two of those children were born, including Daniel Justin Bruyn. After a rise of unrest in France, they returned four years later to England. They came to the Colony of New South Wales in 1856 as assisted migrants. Daniel and Sarah arrived in the Colony on board the Commodore Perry on 1 May 1856 with their children Margaret, Ellen, Elizabeth, Daniel and Sarah. (The eldest child, Joseph, travelled to the Colony a few years later.)

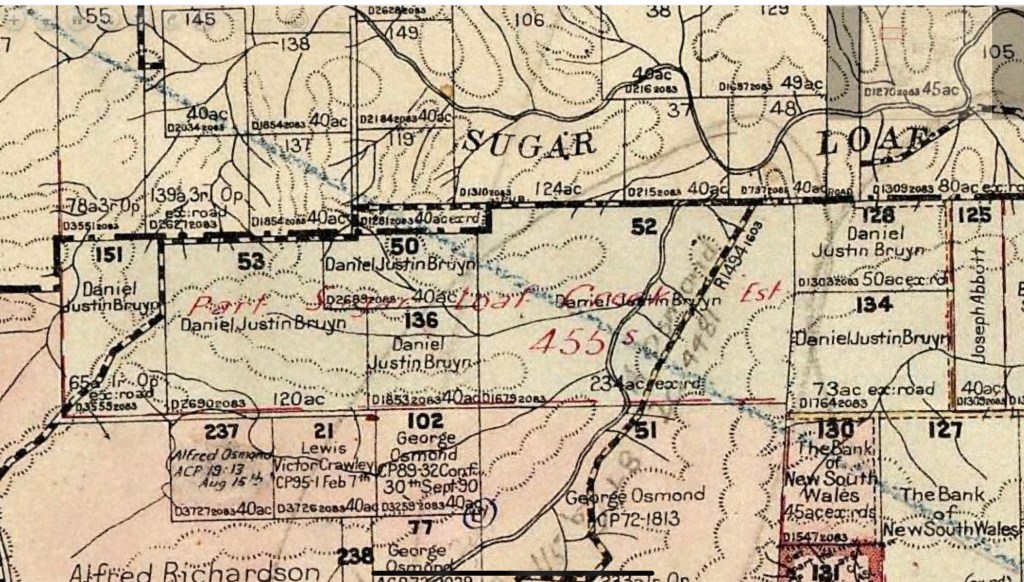

We have seen that Ellen had a sizeable inheritance on the death of her brother, Daniel Justin Bruyn. He had accumulated cash and property over the years, with a thriving business as a Grazier on the lands that he had purchased to the northwest of Dungog. That was given over to her, added to the land that was already under her name.

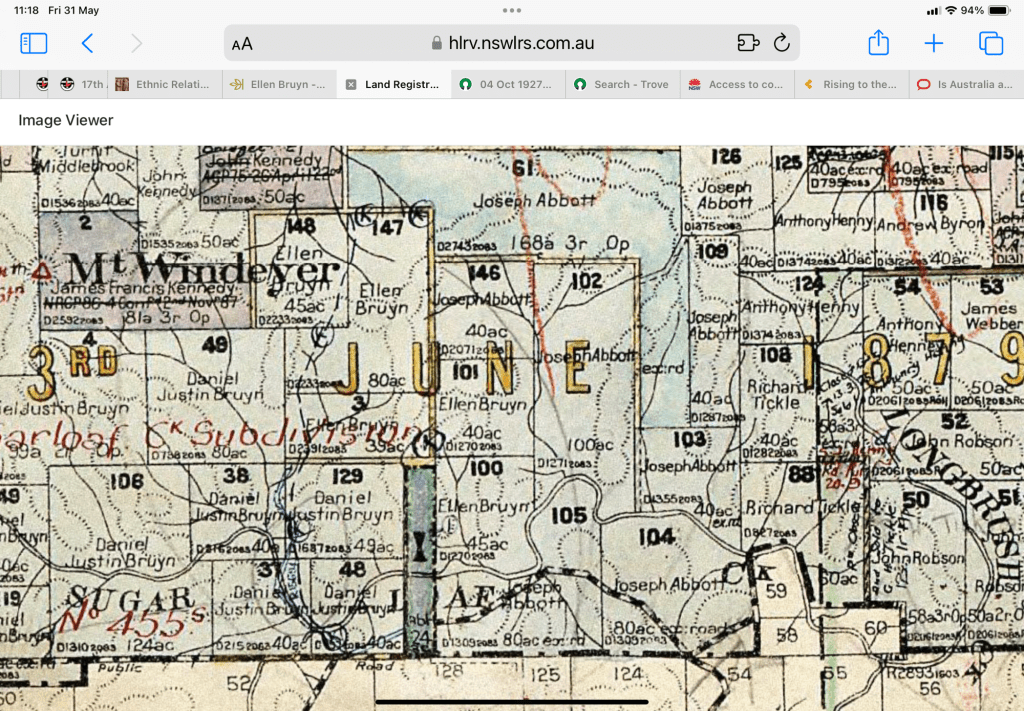

the property owned by Ellen Bruyn

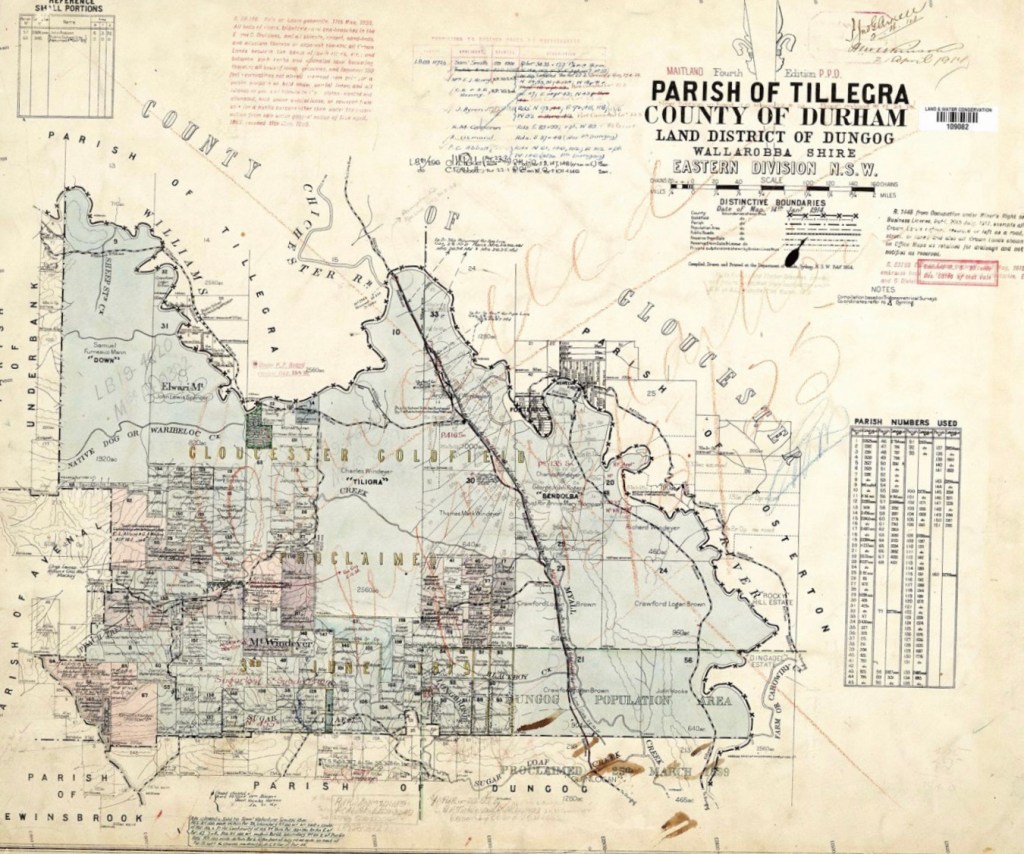

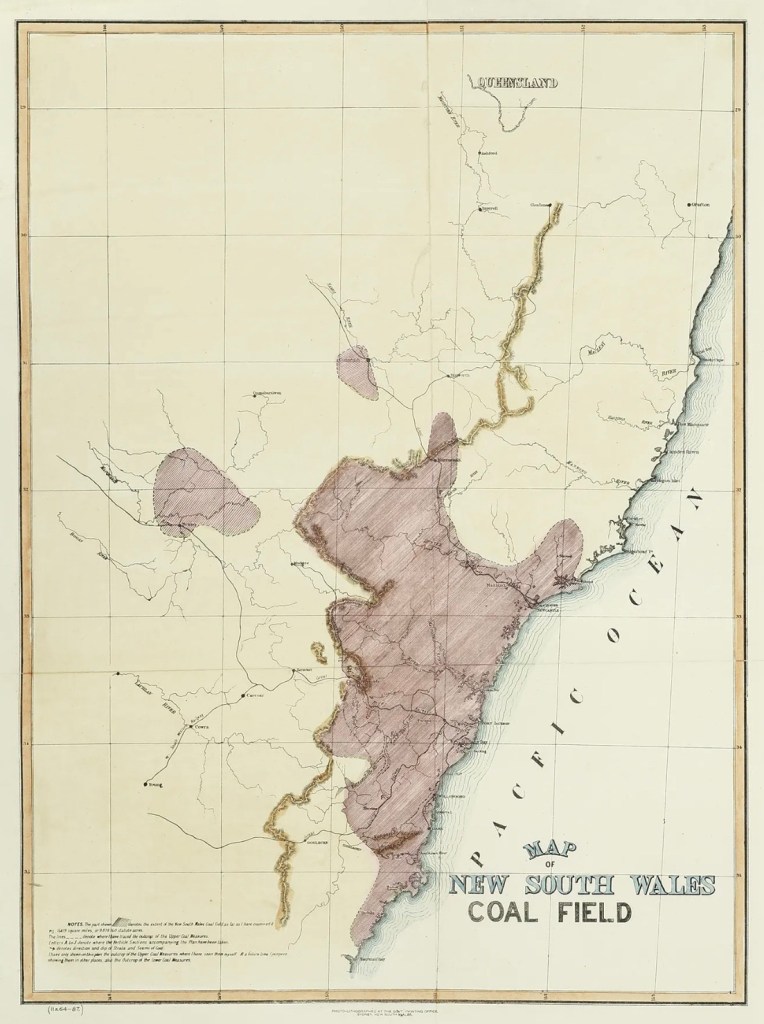

An 1894 survey map for the Parish of Tillegra contains Lots which are registered in the name of Ellen Bruyn: Lots 100 (45 acres), 101 (40 acres), 3 (39 acres), 147 (80 acres), and 148 (45 acres)—a total of 249 acres. This land was located immediately next to land in north-eastern section of the many Lots owned by Ellen’s brother, Daniel Justin, so it is reasonable to suppose that it formed a part of the one large farm stretching along much of the Dungog—Tillegra parish boundary.

So Ellen had a large portfolio to oversee, what with her own land and the land she had received on the death of brother Daniel. She managed this property well over the following decades, using the land to maintain a strong economic position throughout her life. Ellen continued to live in the house in Brown Street where she had spent the latter years of her childhood as well as the early decades of her adult life.

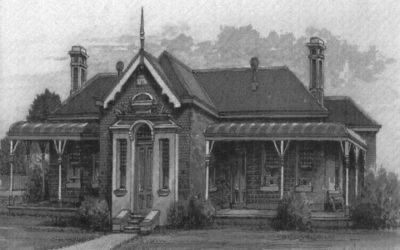

At some point late in the 1890s or, more likely, in the first decade or so of the 20th century, a substantial brick dwelling was built on this site, replacing what was an earlier family home. The 1913 Electoral Roll for Dungog lists “Bruyn, Ellen, Dungog, domestic duties” as a resident. A photo (undated, perhaps in the 1910s?) shows Ellen in her mature years in the garden at the front of this house.

The house appears relatively new; could this be early in the 20th century, or even a few years earlier?

The exterior of the house looks relatively unchanged even today. The sweeping curve of the verandah bricks and the path from the front fence leading to an offset entry can be seen. At the other end of the front verandah, it is evident that there are some people standing there, although identification of individuals is not possible. The front garden reflects a substantial investment of time and care from Ellen over the years.

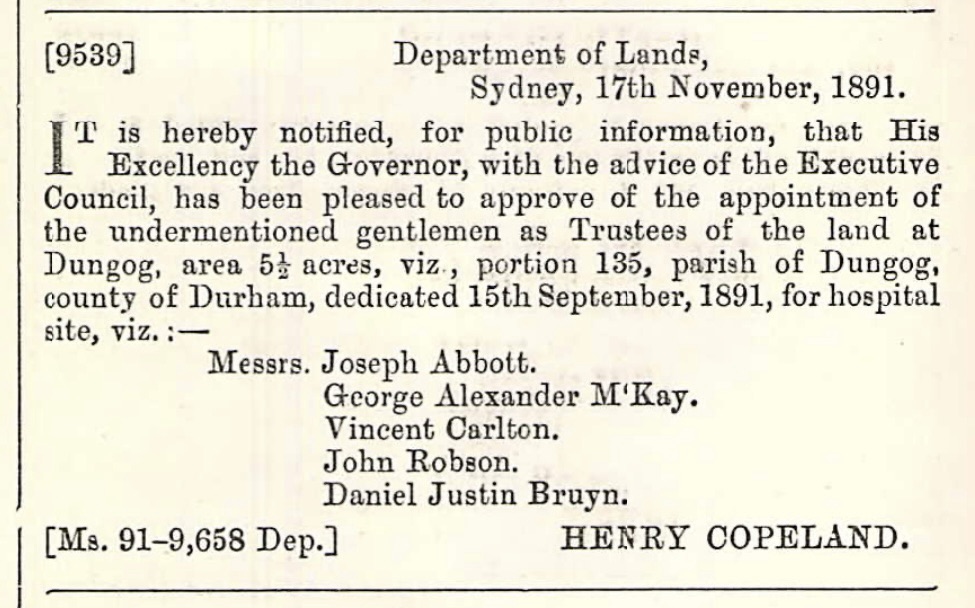

Ellen was a single woman who never married. There are clear indications that Ellen’s bachelor brother, Daniel Justin, had lived in a room in this house over the years before he took his own life in 1912. Daniel had been a well-respected member of the Dungog community. Ellen herself was evidently very involved in charitable and community matters locally—the distribution of funds from her will indicated this very clearly.

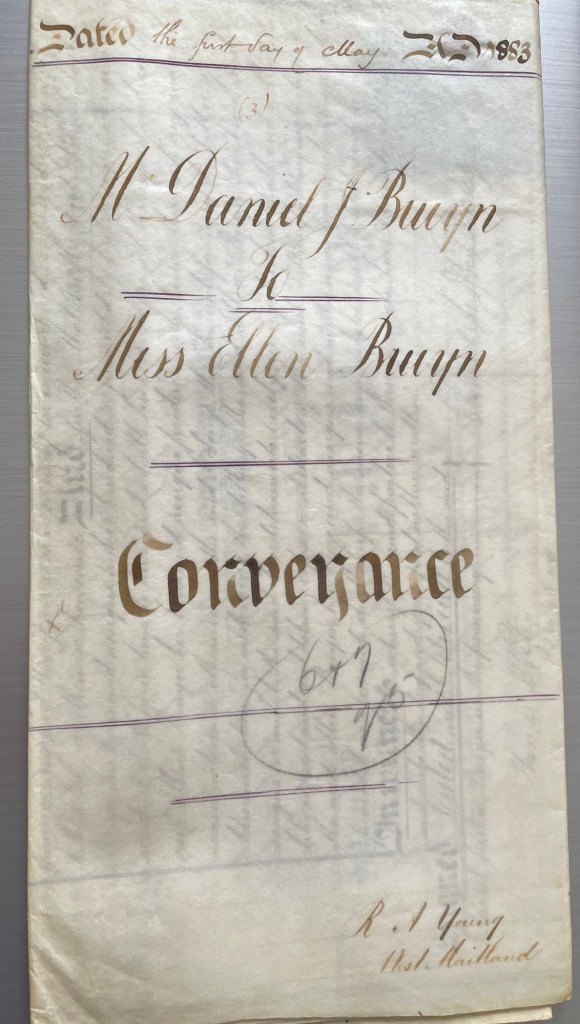

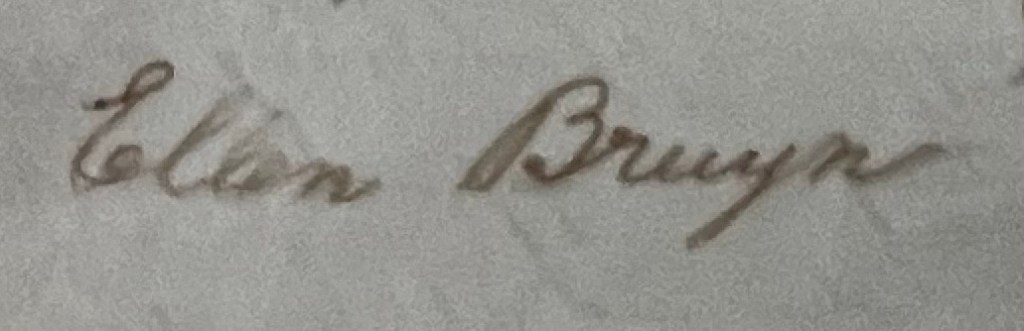

from Daniel Bruyn to his sister Ellen

A Conveyance dated 31 May 1883 between Ellen Bruyn of Dungog, Spinster, and Daniel Justin Bruyn of Dungog, Blacksmith, indicates that Allotment No. Seven of Section No. Five and Allotment No. Six of Section No. Five were sold for the sum of two hundred pounds. Ellen would live there as the owner of the house for almost half a century, until her death in 1927. That property had been made over to Daniel Jnr soon after the death of his father, Daniel Snr, and he subsequently put it up for public auction.

Ellen must have pleased to be the owner of the house that she had been living in for years, as well as the adjacent block of land. Why she had to pay this amount to her brother when she was just as much a child of Daniel and Sarah as he was, is a mystery. The gendered bias in 19th century society would, of course, have meant that the property of the father would normally pass to his son after his death, unless another course of action was specified. Obviously, such an alternative had not been set out by Daniel Snr. So Daniel Justin Bruyn inherited the family home in Brown St, and then his sister Ellen Bruyn bought it off him.

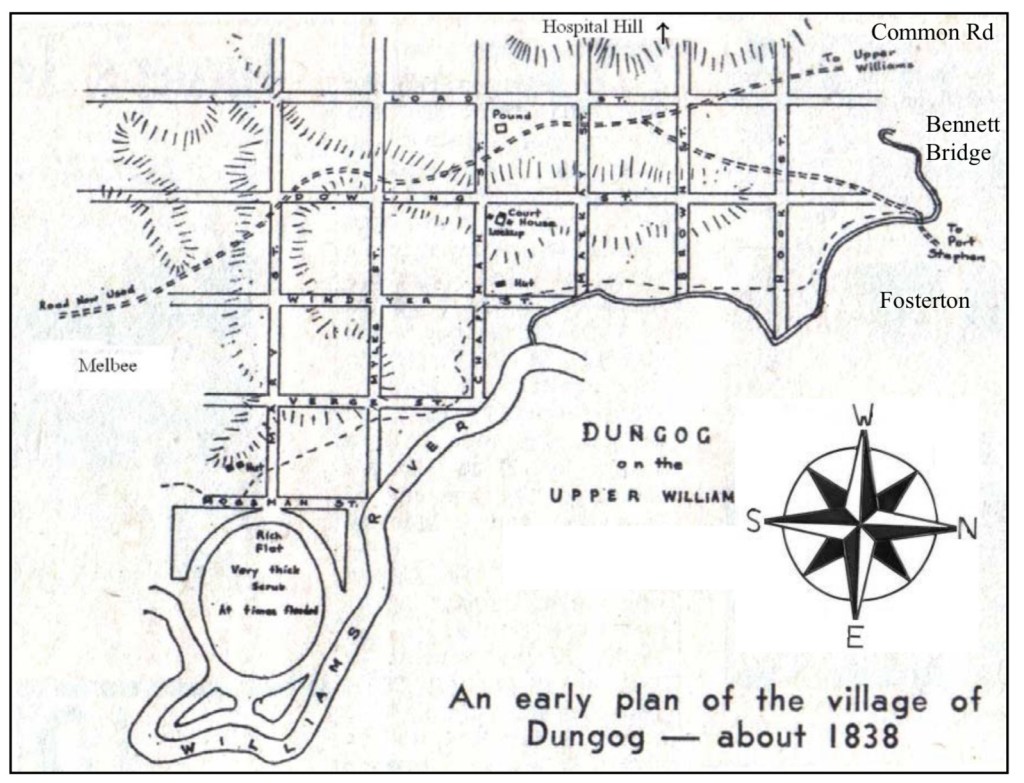

Ellen lived in the houses on this property for many decades—from the 1860s until her death in 1927. Over this time, she would have seen the town of Dungog grow and develop over the years. In her study of towns and buildings in the region, Grace Karskens writes that Governor Darling “published regulations for town planning in 1829 which directed that streets be laid out in a grid pattern, and emphasised uniformity and regularity, wide streets, half-acre allotments, and that buildings were to beset well back” (Dungog Shire Heritage Study: Thematic History, 1986, p.51). This set the pattern for numerous country towns, including Dungog.

This neat, orderly development continued for some decades. Karskens notes that “the second half of the nineteenth century was generally a boom-time for the major towns in Dungog Shire, and thus also a period of physical consolidation and community growth” (p.63).

The pattern that she observes in the 1860s was certainly evident in Dungog: “neat, solid government buildings, such as police stations, watch houses, post offices and court houses, all built to indicate a civilized and well-ordered society. Rows of stores and offices were built by merchants, professional people, banks and businessmen along the main streets, slowly filling up the grids laid down by surveyors forty years before.” (p.63).

Karskens cites an unidentified press clipping held in the Newcastle Local History Library when she observes that “during the 1850s, Dungog, like Clarence Town, benefited from a position on the route to the Peel River and Gloucester goldfields, and this was repeated during the 1880s with the finds at Wangat (within the Shire), Whispering Gully and Barrington” (p.80).

She reports that “an anonymous correspondent writing in 1888 listed the town’s businesses as including three banks, four hotels, four large general stores, three butchers, three bakers, a coachmaker, wheelwrights, three blacksmiths, a hairdresser, a fancy tailor, boot makers, three saddle and harness makers and four churches, a weekly newspaper and ‘a School of Arts a credit to any town’.” (p.81). Included among those three blacksmiths, of course, was Daniel Joseph Bruyn, Ellen’s father.

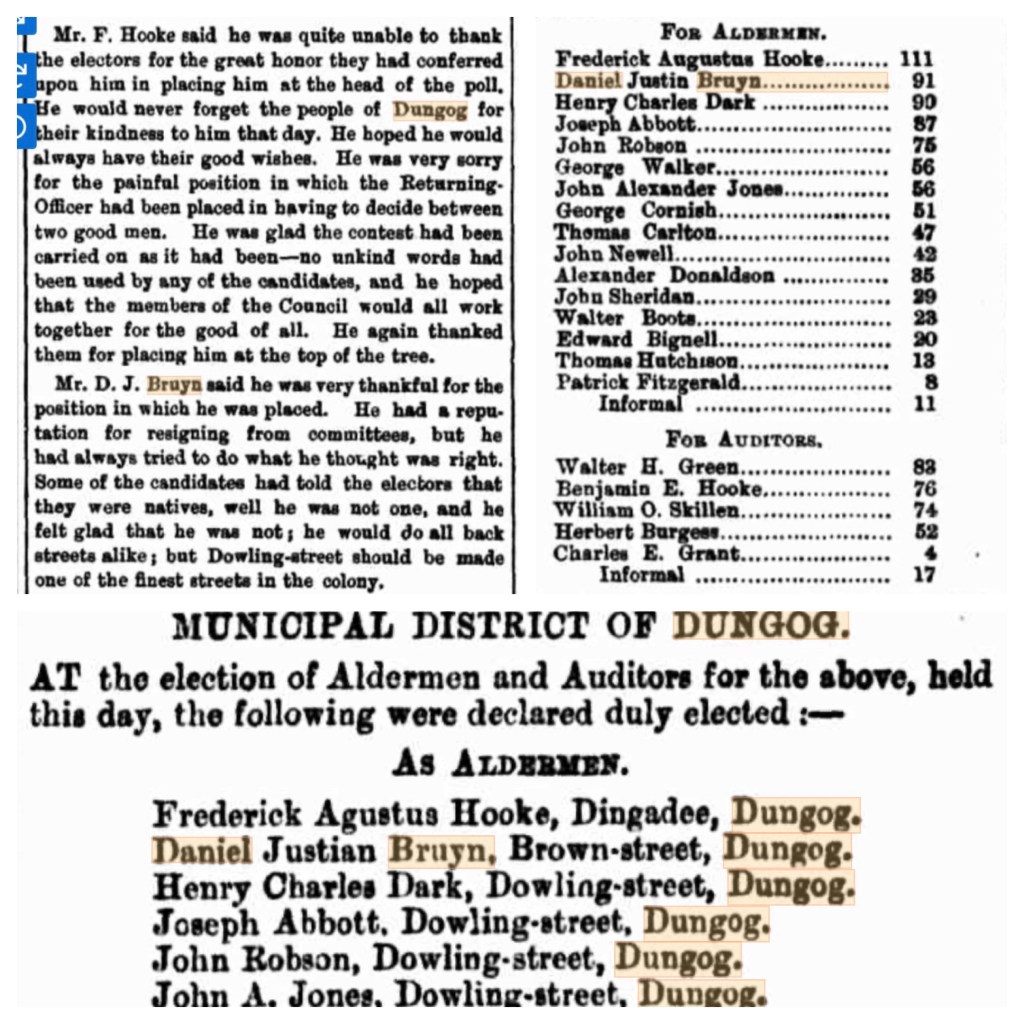

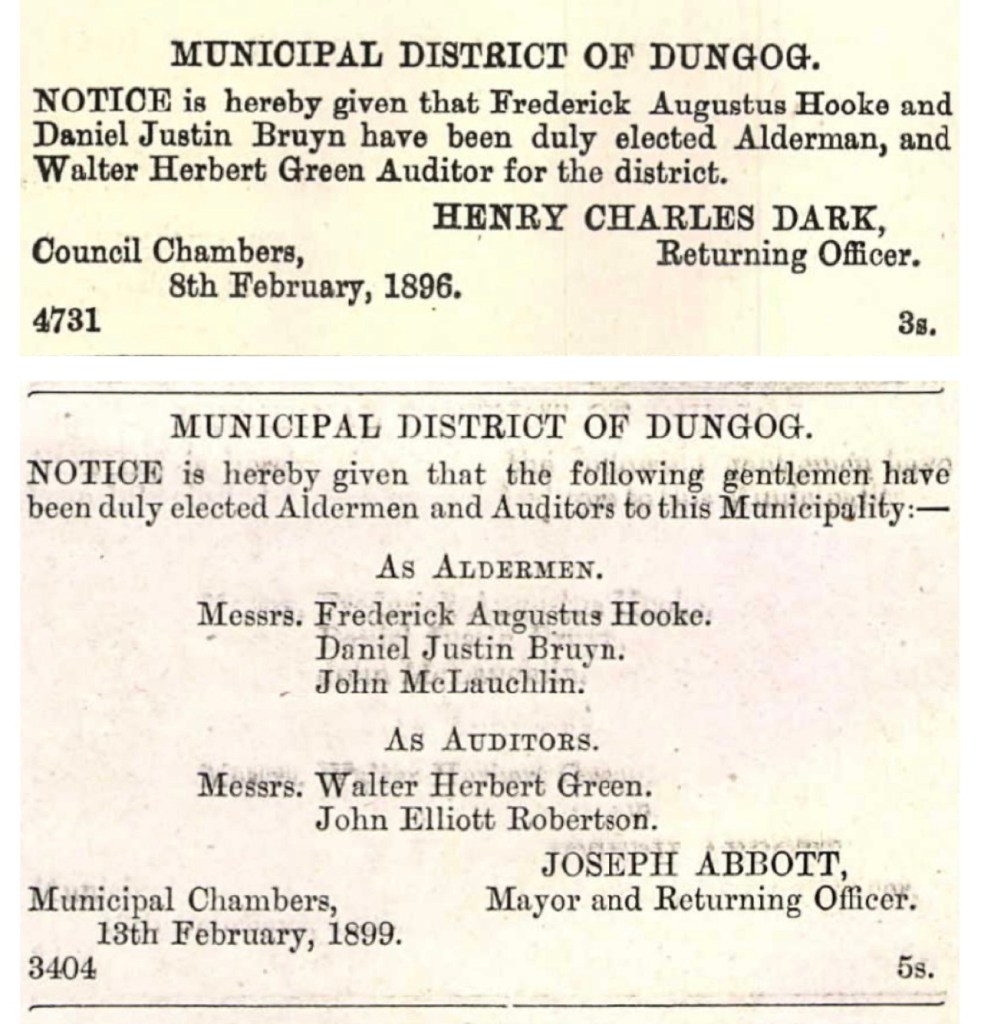

Growth in the town continued year by year. Karskens notes that “Dungog Cottage Hospital was opened in 1892 in a small (two-roomed) ornate Italianate brick building in Hospital Street at the western end of town” (p.82) and in the following year the town was proclaimed a Municipality and elections were held for councillors for the first Dungog Municipal Council. The new council would have responsibility for services in the town of Dungog and the rest of the newly-formed shire.

Along Dowling St, the new buildings included the Roman Catholic Church and Presbytery (1880s, now Tall Timbers Motel and the Information centre), an Italianate Post Office (1874, with a less dramatic facade added some decades later), the Oddfellows Hall (1881, now the Dungog Medical Practice), the ornate CBC bank and residence (1884, now a private residence), Centennial Hall (1888, now a cafe), the Bank Hotel (an 1891 conversion of a former residence), the Skillen and Walker Terrace (1895, four two-story shops-and-residences with a central archway), the School of Arts (1898, now the Historical Society), and the Angus and Coote building (1911).

After the death of her father in 1883, Ellen Bruyn had bought the land in Brown Street where the family had lived for around 30 years. As the town continued to grow, a number of significant buildings were erected near to this residence. On the corner of Brown and Dowling Sts, Dark’s Store was built in 1877 and expanded in each of 1896, 1900 and finally in 1920. It came to be called “the hall of Commerce” and housed the largest store in Dungog. Opposite this was the striking Coolalie, built in 1895 as the home of Henry Charles Dark.

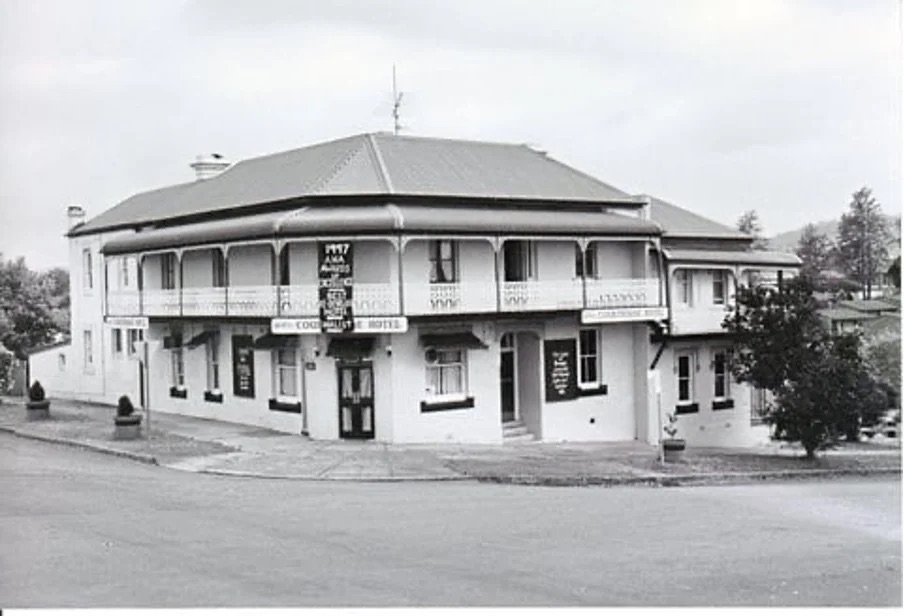

In Brown Street itself, Dungog’s oldest hotel, the Court House Hotel, now the Settler’s Arms (pictured above), had been trading since the 1850s. On the top of the hill, the Roman Catholic Convent of St Joseph was built in 1891, a Parish Hall in 1913, and a new Church in 1933, six years after Ellen died. As a devout Catholic, she would have been a regular attendee at the Church on Dowling St and, in later years, at Parish events in the Hall on Brown St. On the eastern end of Brown St, the James Theatre was opened in 1918; to the west of the Bruyn residence, a large and impressive Memorial Hall (now the RSL club) was built in 1919.

(from https://www.newcastleherald.com.au/story/

1208160/dungog-cinema-celebrates-100-years/)

(The information about these buildings is taken largely from Michael Williams’ 2011 publication, Ah, Dungog! A brief survey of its charming houses and historic buildings.)

So the hypothesis that Elizabeth and I have developed is that, after she had bought the property in Brown St in 1883, with the older family home on it, Ellen Bruyn had a new double-brick house built on Lot 6.

Which opens the next stage as the story continues … … …

and see earlier blogs at