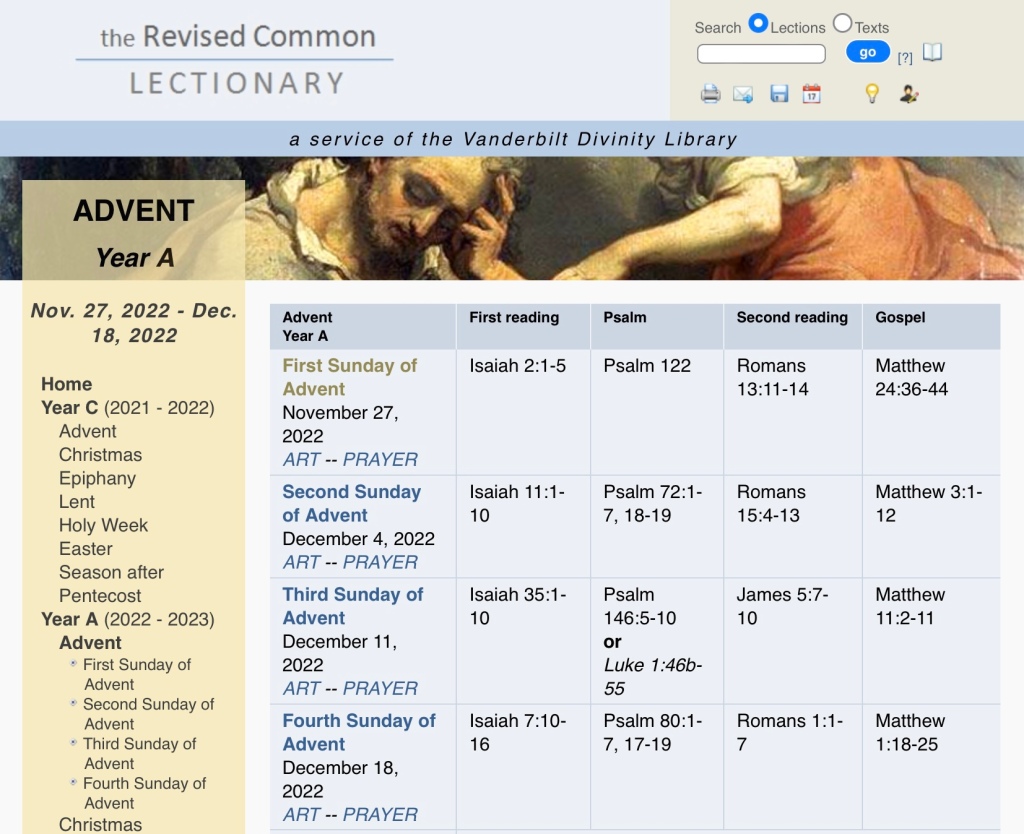

As we move on in the very new year in the church’s calendar, this coming Sunday we celebrate the second Sunday in the season of Advent, and continue our preparations for Christmas—the coming of Jesus, Saviour, chosen one, and Lord (Luke 2:11). During Advent, the lectionary offers a selection of biblical passages designed to help us in our preparations, building to the climactic moment of Christmas Day, when we remember that “the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14).

These scripture passages include a sequence of excerpts from the Hebrew Scriptures—largely from the book of Isaiah—which orient us to the saving work of God, experienced by faithful people in Israel through the ages. These scripture passages lead us along a path that brings us to the point when we can sense God’s work in the story of Jesus.

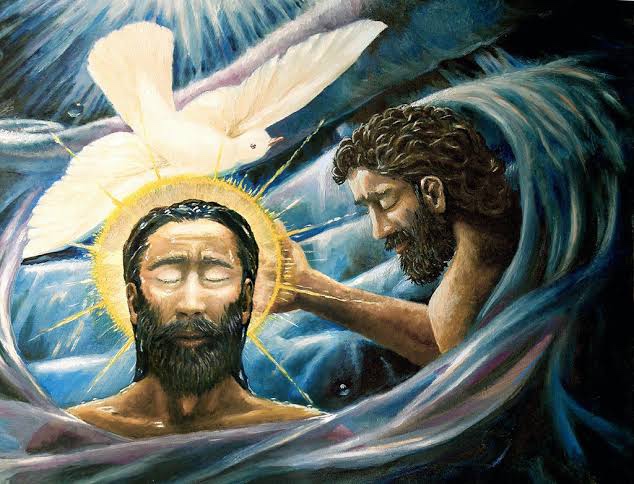

The passage proposed for this second Sunday in Advent is a very well-known one; it is cited near the beginning of all four canonical Gospels, where it is used to describe what John the baptiser was doing as he called people to repentance and baptised them by dunking them in the River Jordan (Mark 1:2–5; Matt 3:3–6; Luke 3:1–6; John 1:24–28). One reason for hearing this Hebrew Scripture passage on Advent 2 may well be that the account of John, preaching and baptising, is the Gospel reading for this Sunday (Mark 1:1–8).

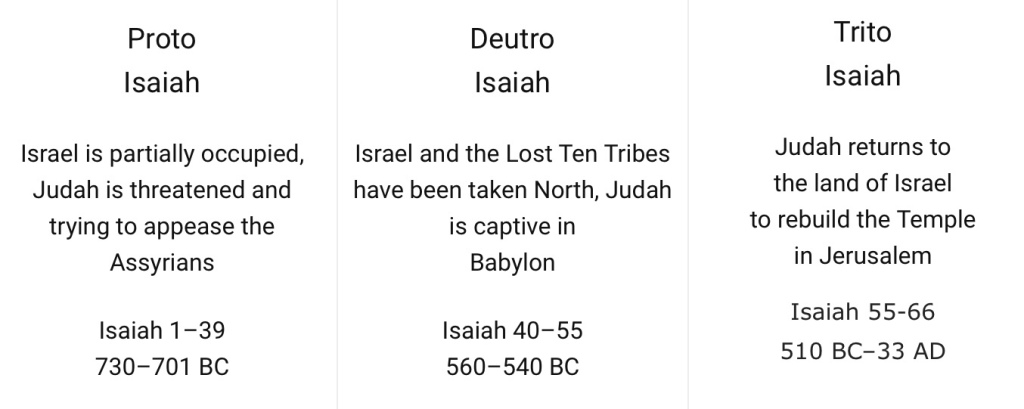

Whilst the voice which cries out “in the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord” (Isa 40:3) is applied directly to John in the Gospels, it has a different reference in its original context. The words of the exilic prophet whose work forms the second section (chs. 40–55) are oriented towards the appearance of God to the people of Israel as they wait and hope for the end of their exile in Babylon. The prophet says that God will comfort the people (v.1), speaking tenderly to Jerusalem, declaring that “her penalty is paid” (v.2)—and then, that “the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all people shall see it together” (v.5).

In the ensuing chapters, the prophet sets out the promise of God: “I will send to Babylon and break down all the bars, and the shouting of the Chaldeans will be turned to lamentation” (Isa 43:14; 48:14; and see the extended oracle of 47:1–15). He specifically nominates Cyrus of Persia as the one chosen (or anointed) by God to bring the exiles home (Isa 44:28—45:1; 45:13).

The prophet describes the journey leaving Babylon and returning to Jerusalem in terms reminiscent of the journey that Israel undertook in the wilderness, after leaving Egypt (Isa 41:17–20; 43:16–17; 49:9–10; 50:2). Because it was the Lord who “dried up the sea, the waters of the great deep [and] made the depths of the sea a way for the redeemed to cross over”, the prophet declares exultantly, “the ransomed of the Lord shall return, and come to Zion with singing” (Isa 51:10–11).

So the voice crying out in the original prophecy is not calling the people to repentance, but noting that they have already served their time of punishment (Isa 40:2), and that God is acting now to save them (43:3, 11; 45:15, 21; 49:26). Of Jerusalem, the prophet declares, “she has served her term … her penalty is paid … she has received from the Lord’s hand double for all her sins” (Isa 40:2).

Rather than declaring the judgements that are coming from the Lord in God and sounding a call to repentance, like the earlier pre-exilic prophet had done (Isa 1:27; 2:5; 5:1–7), this exilic prophet emphasises the positive deeds of the Lord as the exiles prepare to return to the land. The Lord will gather people from nations in all four directions into the land (Isa 43:5–7, 9) and will do “a new thing” for the people (Isa 42:9; 43:19; 48:6).

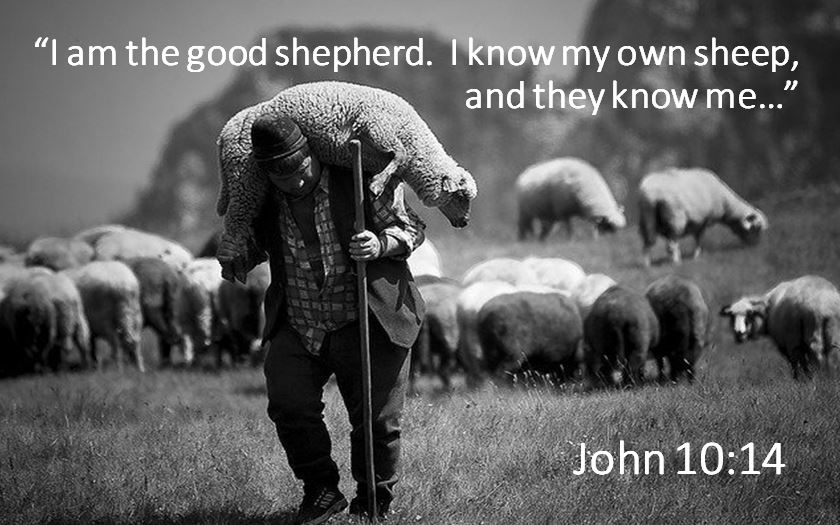

It is the statement about how the Lord will act that comes in the final verse of the prophetic passage which the lectionary offers for this coming Sunday (Isa 40:1–11) which resonates with us as we hear and ponder this passage at this time of the year (the second Sunday in Advent). The Lord God, we are told, “will feed his flock like a shepherd; he will gather the lambs in his arms, and carry them in his bosom, and gently lead the mother sheep” (Isa 40:11).

God, says the psalmist, is “Shepherd of Israel, who lead[s] Joseph like a flock” (Ps 80:1). Elsewhere, a psalmist sings, “he is our God, and we are the people of his pasture, and the sheep of his hand” (Ps 95:7); and of course the opening line of perhaps the best-known psalm is simply, “the Lord is my shepherd” (Ps 23:1).

The prophet Ezekiel declares that God himself “will search for my sheep, and will seek them out. As shepherds seek out their flocks when they are among their scattered sheep, so I will seek out my sheep” (Ezek 34:11–12). Ezekiel then extends this role to the king when he reports God’s words: “my servant David shall be king over them; and they shall all have one shepherd” (Ezek 37:24).

And then another exilic prophet most dramatically describes Cyrus of a Persia as both the Lord’s anointed one (Isa 45:1) and the one of whom the Lord says, “he is my shepherd and he shall carry out all my purpose” (Isa 45:28). That is a striking extension of the strong scriptural imagery of the shepherd, normally applied to the God of Israel or rulers within Israel, which is now placed onto a foreign ruler.

In this season of Advent, as Christians anticipate the celebration of Christmas, the scriptural imagery of the shepherd caring for their flock evokes Jesus, whose birth is remembered at Christmas. The birth of Jesus was first announced to shepherds, who were the earliest visitors (according to Luke) to the newborn and his parents (Luke 2:8–20). Mark and Matthew report that Jesus, as an adult, “had compassion for [the crowd], because they were like sheep without a shepherd” (Mark 6:34; also Matt 9:36).

And in one of his famous teaching sections in John’s Gospel, Jesus declares that he is the shepherd (John 10:11)—indeed, “the good shepherd” (John 10:14), “the good shepherd [who] lays down his life for the sheep” (John 10:11). Jesus himself extends the metaphor, noting that there are “other sheep that do not belong to this fold” and promising that “I must bring them also, and they will listen to my voice; so there will be one flock, one shepherd” (John 10:16).

Many in his Judean audience were not impressed at the way that Jesus, in these words, took on a key function of God and claimed it for himself. “He has a demon and is out of his mind. Why listen to him?”, they said (John 10:20). Aggrieved by Jesus’ claim, “the Father and I are one” (John 10:30), they sought to stone him, recalling the earlier antagonism of Judeans who sought to kill Jesus when he was “calling God his own Father, thereby making himself equal to God” (John 5:18). It seems that the care shown by this shepherd for his sheep failed to evoke the same response from his audience.

So this ancient prophecy reaches out across centuries, from Babylonian exile to Roman oppression, and on into the postmodern 21st century, with a promise of compassionate care for the people of God. Whilst the prophet was describing how God would care for the people of Israel in his time, the underlying dynamic is applicable, with due care, to the relationship of Jesus to his people, centuries later. It is in this regard that we can hear and read this passage as one that is appropriate for the season of Advent.