The Gospel for the first Sunday in the season of Christmas (Luke 2:41–52) tells a story found only in this Gospel. It is set when Jesus was twelve years old, and he goes missing on what Luke reports was an annual pilgrimage to Jerusalem for the Passover festival (Luke 2:41).

The canonical Gospels included very little at all about the childhood of Jesus: Mark and John have nothing at all, while Matthew leaps from the two-year Jesus to his adult years, and Luke has only a couple of stories about the infant Jesus in the temple—except for this passage, set twelve years later. Because of this absence of material about the childhood of Jesus, from the second century onwards, various works were produced which recounted tales of “the missing years” of the childhood of Jesus.

Some of these works focussed on expanding the story of the birth of Jesus. The Protoevangelium of James, also known as The Infancy Gospel of James, is a mid-2nd century work, which provides many more details than found in the canonical infancy narratives. It claims that Mary was a temple virgin who remained a virgin for her entire life. I have explored some of the content of this work in

The Infancy Gospel of Matthew, also known in antiquity as The Book About the Origin of the Blessed Mary and the Childhood of the Saviour, offers an expanded account of the Flight into Egypt (it is not known on what this is based), and an edited reproduction of The Infancy Gospel of Thomas. This work which bears Mary’s name in the alternative title is dated to the 8th century; it has been the basis for developing Catholic traditions about Mary which still hold sway in popular piety.

In The Infancy Gospel of Thomas, a Gnostic work of perhaps the late second century, elaborated stories about the childhood of Jesus are told. One writer has described it as “a flamboyant and entertaining account of Jesus as a little child growing up in his hometown”.

See Michael J. Kruger, “What’s the earliest record of Jesus’s Childhood?” at https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/earliest-record-jesus-childhood/

The most famous incident in this work is when Jesus created gives clay birds on the sabbath; when accused of breaking Torah by working on the sabbath, he clapped his hands and the birds came to life and flew away! (The story is retold in the Quran, 5.10.) But Jesus in this Gospel also curses other children and causes some of them to die.

The last story it tells is of the twelve year old Jesus in the Temple, which we know from Luke 2:41–52. In Luke’s version, the teachers of the Law heard Jesus and “they did not understand what he said to them” (Luke 2:50). In the version told in Thomas, in this place in the story there stands this interchange between Mary and the scribes and Pharisees: “‘Are you the mother of this child?’ She said ‘I am’. And they said to her, ‘Blessed are you among women because God has blessed the fruit of your womb. For such glory and such excellence and wisdom we have neither seen nor heard at any time.’” (Infancy 19:4).

Most manuscripts that we have of this Gospel are medieval, although a fragmented manuscript of this work, dated to the fifth century, is held by a German library. For a translation of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas from the medieval manuscripts , see http://www.gnosis.org/library/inftoma.htm

Other later texts that contain material on the childhood years of Jesus include The Syriac Infancy Gospel (sixth century?) and The History of Joseph the Carpenter (seventh century?). The earliest manuscripts we have for these works are medieval.

So the story that Luke includes, from the end of the childhood years of Jesus, is somewhat related to these non-canonical works, in that it reveals a curiosity about the earlier years of Jesus. Perhaps Luke includes this story to satisfy a little of that curiosity. However, Luke’s story is quite different from these non-canonical accounts, which inevitably are speculative, flamboyantly elaborated, and utterly unreliable as any form of historical evidence.

The story told by Luke relates to some central themes found throughout his two-volume work. A number of elements in the story point forward to themes that recur later in the Gospel.

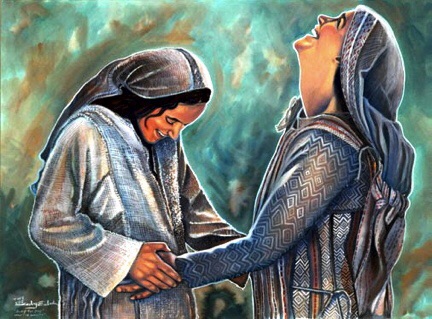

First, the setting is the Temple (2:46). In the Lukan version of the story of Jesus, the Jerusalem Temple plays a significant role. His “orderly account of the things that have been fulfilled among us” begins in the temple in Jerusalem, where we meet faithful Jewish people, Zechariah and Elizabeth (Luke 1:8–22) and then Simeon and Anna (2:22–38). This is the only Gospel that refers to these figures.

In Luke’s account of the story of the testing of Jesus (Luke 4:1–14), the order of testings found in Matthew’s account is altered, so that the testing relating to the Jerusalem Temple is placed at the climactic point of the last testing (4:11–13).

At a crucial point during his ministry in Galilee, Jesus “sets his face” to go to Jerusalem (9:51). On the way towards Jerusalem, Jesus laments the fate that is in store for Jerusalem (13:33–35) and when he enters the city, he weeps over the city (19:41–44) and provides more prophetic words about their fate (21:20–24). Each of these passages is found only in this particular Gospel.

Once Jesus has arrived in the city, the narration of his arrest, trial, betrayal, sentencing, death and burial follows the pathways recounted in other canonical Gospels. However, the risen Jesus appears, not in Galilee (as in other versions), but only in the nearby town of Emmaus (24:28–32) and then in Jerusalem itself (24:33–49). The final sentence of this Gospel indicates a return to the location of the opening scene, as the disciples “were continually in the temple blessing God” (24:53; cf. Acts 1:8–9).

The Lukan focus is singularly on the early movement as it formed in Jerusalem (Acts 1—7, 12) before spreading out from Jerusalem into other regions. Indeed, Acts 1:8 provides a programmatic statement that prioritises Jerusalem amongst all locations. And the disciples are noted as being in the temple a number of times (Acts 2:46; 3:1: 4:1–2; 5:21, 42). Indeed, this is specifically commanded by an angel of the Lord, who said, “Go, stand in the temple and tell the people the whole message about this life” (Acts 5:20). The Temple is a highly significant location in this Gospel.

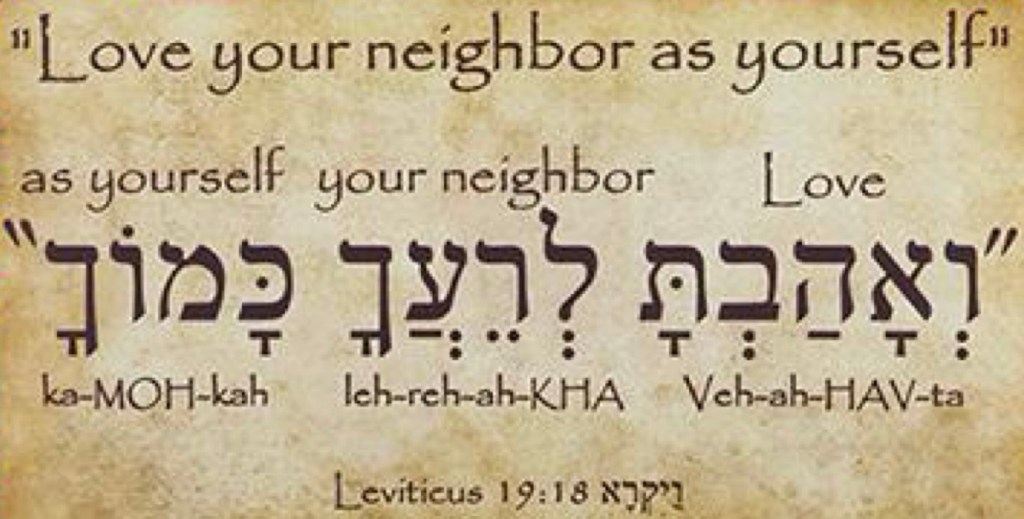

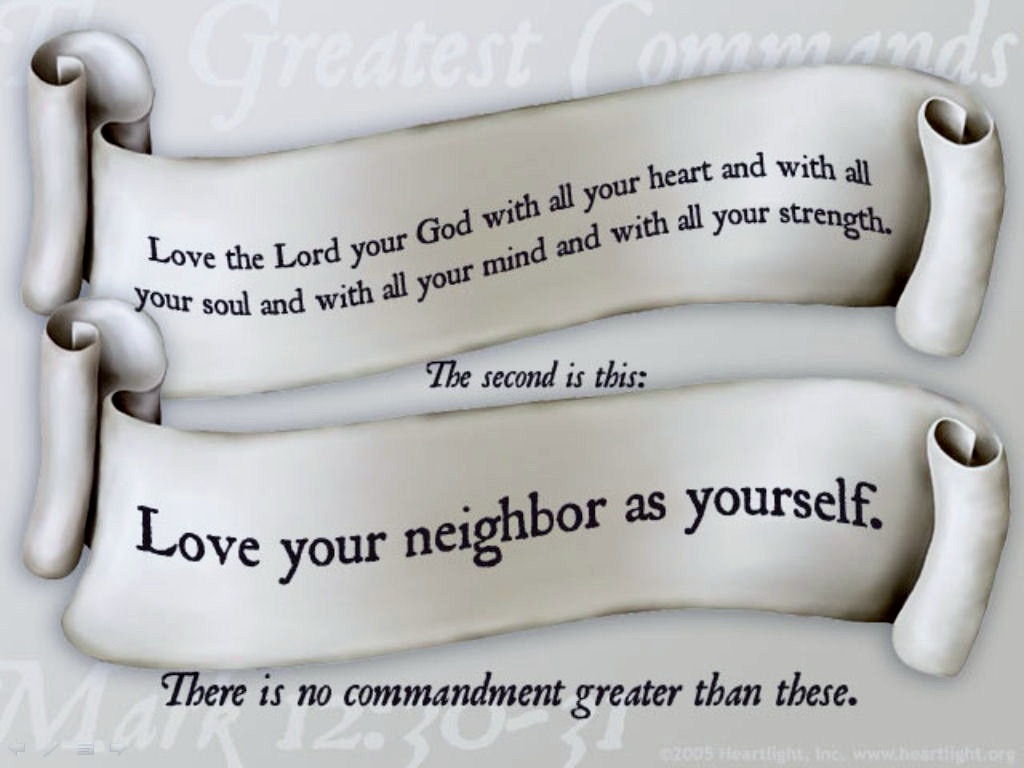

A second important feature that points ahead is the fact that Jesus is engaged in discussion with the teachers of Torah. When he was found, he was “sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions” (Luke 2:46). Discussion about Torah runs through Luke’s narrative, just as it had done in the Markan source that we presume he used (5:17–26; 6:1–5, 6–11; 10:25–37; 11:37–52; 12:1–3; 13:10–17; 14:1–6; 16:14–18; 18:18–30; 20:1–47).

Indeed, such is the vigour with which Jesus debates the teachers of Torah that “the scribes and the Pharisees began to be very hostile toward him and to cross-examine him about many things, lying in wait for him, to catch him in something he might say” (11:53–54). And then “the elders of the people” conspire with the Temple authorities to arrest Jesus (22:52) and bring him to trial (22:66), “vehemently accusing him” when he is brought before Herod (23:10) and pressing Pilate to sentence him to death (23:13–18).

However, all of this is far into the future as the twelve year old Jesus sits in the Temple, “sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions” (Luke 2:46). The response at this stage is positive and encouraging; Luke comments that “all who heard him were amazed at his understanding and his answers” (2:47). The story thus points to the way that amazement will be the response of people later in Luke’s narrative when the adult Jesus teaches and heals (4:22, 36; 5:9, 26; 8:25; 9:43; 11:14).

A third element looking ahead to later in the Gospel occurs in the words spoken by Jesus. During this exchange in the Temple, the young Jesus speaks words of wisdom. “Did you not know that I must be in my Father’s house” (2:49) is the first example of many of the short, pithy sayings which Jesus speaks throughout the Gospel.

We know this kind of saying well: “the Son of Man is lord of the sabbath” (6:5), “do to others as you would have them do to you” (6:31), “wisdom is vindicated by all her children” (7:35), “let anyone with ears to hear listen!” (8:8), “my mother and my brothers are those who hear the word of God and do it” (8:21), “if any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me” (9:23), “whoever is not against you is for you” (9:50) … and so on. The words of Jesus in this story, “I must be in my Father’s house?” (2:49) prefigure this wise saying style of Jesus.

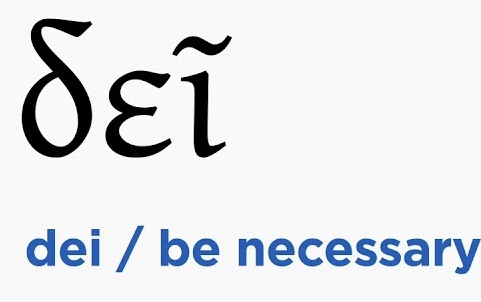

And the one small word “must” plays a key role at the centre of Luke’s theological explanation that all that takes place is integral to “the plan of God” (see esp. Acts 2:23 and Luke 7:30). (This was the topic for my PhD thesis, published as The plan of God in Luke-Acts, CUP, 1993; one whole chapter was devoted to the motif of divine necessity that is conveyed by this word and a cluster of terms used in Luke—Acts.)

What “must” take place is Jesus’s proclamation of the kingdom of God (Luke 4:43), the suffering of the Son of Man (9:22; 17:25), the necessary journey on the road to Jerusalem (13:34), and the inevitable occurrence of wars and insurrections (21:9), the flight from Jerusalem (21:20–21),, and the death of Jesus itself (22:36–37), followed by his being raised from the dead (24:7, 44–46). In Acts, this divine necessity continues to impel the activities of the apostles (Acts 4:19–20; 5:29) and of Paul (9:16; 14:22; 19:21; 23:11). All of this (and more) “must” take place.

Indeed, an alternative translation of Jesus’ words from the Greek, οὐκ ᾔδειτε ὅτι ἐν τοῖς τοῦ πατρός μου δεῖ εἶναί με; (and the translation that I prefer) is that he says “do you not know that I must be about the business of my Father?”. This rendering highlights how this verse performs a key programmatic function for the Gospel narrative as a whole, which tells of how Jesus carries out the business of his Father. That adds another depth to the significance of this passage.

Finally, what might we make of the fact that in this story Jesus was twelve years of age? Modern readers might connect this note with the fact that today, Jewish boys celebrate their bar mitzvah—a coming-of-age ritual—when they turn 13. (Jewish girls have a similar ceremony, a bat mitzvah.) So could this story about the 12 year-old Jesus somehow relate to his own bar mitzvah?

However, there is no reference to a bar mitzvah ceremony in the Hebrew Scriptures or the New Testament, nor in later rabbinic texts such as the Mishnah (3rd century) and the Talmuds (5th to 7th centuries). There is discussion in various medieval rabbinic texts that begins to develop the idea that such a ceremony was known; but as is always the case with rabbinic discussion, the discussions are subtle, complex, and not crystal clear to those not used to reading these kinds of texts.

My Jewish Learning places the first reference to a bar mitzvah in a fifth-century rabbinic text which references a blessing to be recited by the father thanking God for freeing him from responsibility for the deeds of his child, who is now accountable for his own actions. However, this is simply a prayer, not a full ritual ceremony. It then notes: “A 14th-century text mentions a father reciting this blessing in a synagogue when his son has his first aliyah [the “going-up” to the front of the synagogue to be blessed]. By the 17th century, boys celebrating this coming of age were also reading from the Torah, chanting the weekly prophetic portion, leading services, and delivering learned talks.”

See https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/bar-and-bat-mitzvah-101/

So we should not read any magical significance into the age of Jesus in the story that Luke tells, other than it seems to mark a moment in the orderly account that Luke writes which reveals something of the character of Jesus at a time well before his public adult activity began. We can’t attribute any historical value to the story (the author of Luke’s Gospel was probably not even born at the time that this story was alleged to have taken place). But it does play an important role in the literary structure of the Gospel—it is a hinge between the infant Jesus and the adult Jesus—as well as offering some key theological elements in the understanding of Jesus that this Gospel develops.