Last Sunday we heard the story of David’s adultery with Bathsheba (2 Sam 11:1–15). It’s a story that has been known and remembered through the ages—although it has often been badly misinterpreted, in explanations that “blame the woman” for what, in the text, is clearly a series of actions undertaken explicitly by the man who has power, the man who decides to “take” the woman.

As we have seen in previous blogs, the person who emerges with most integrity from the story of David’s adultery and murder is Bathsheba. In the custom of the day, she had no choice but to obey the King and allow him to “lie with her” and make her pregnant (11:4–5). Bathsheba fittingly mourns for her husband (11:26). She will remain faithful to David, as king, over the years, as well as to her child, Solomon, who later becomes king (from 2 Sam 11:27 through until 1 Kings 2).

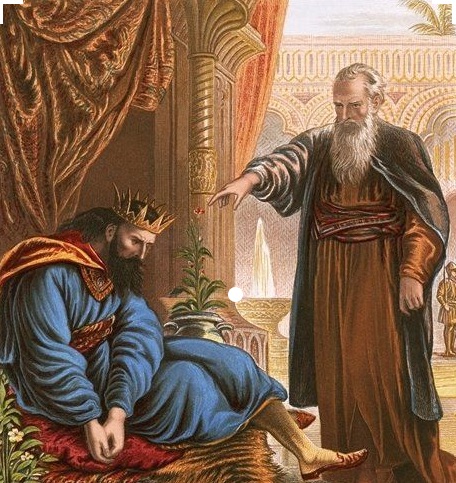

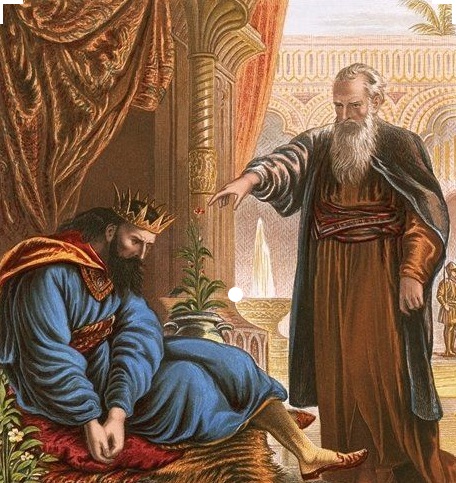

David, by contrast, continues his unseemly behaviour. In the passage that we hear this Sunday (2 Sam 11:26—12:13), the prophet Nathan regales him with a tale of a rich man with “very many flocks and herds” and a poor man with “nothing but one little ewe lamb” who was much loved and was “like a daughter to him” (12:1–3). Nathan’s story ends with a powerful punchline: “he took the poor man’s lamb, and prepared that for the guest who had come to him” (12:4). The point is clear; the rich man has acted unjustly.

David immediately erupts in anger at the selfish acts of the rich man. “As the Lord lives”, he exclaims, “the man who has done this deserves to die” (12:5). As was to be expected of the king—who was execute justice in Israel (Ps 72:1; 99:4; 1 Ki 10:9)—punishment for this selfish deed was rightly to be implemented.

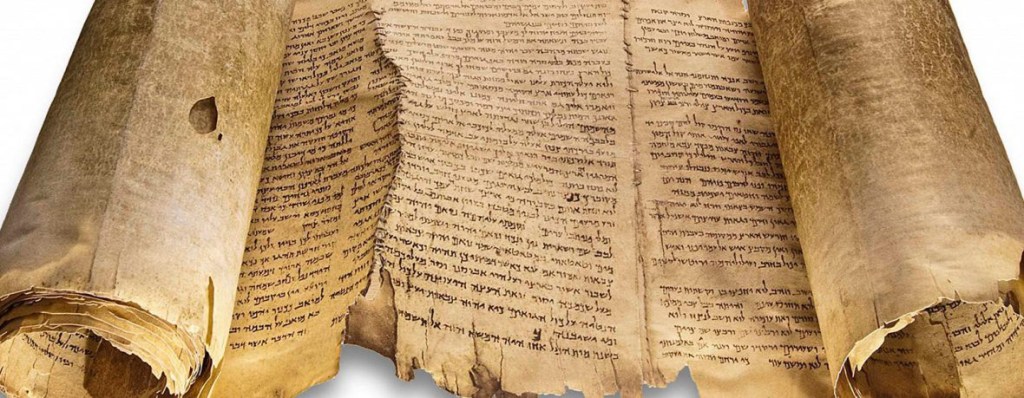

What provoked this strong response? The prophet has told the king a story which cut right to his heart. We recognise this story as a parable, perhaps the best-known of all parables in the Hebrew Scriptures. Jesus, we know, used parables as the chief means of his story-telling. A parable is a story told in a specific way, often to make a single clear point. Parables are conundrums. They contain unresolved tensions. They invite multiple understandings. They press for exploration and investigation.

The parable form used by Jesus has deep roots in Hebrew traditions. In Hebrew Scripture, there are examples of the short, sharp, pithy parables, often identified as a ḥidah, or riddle. A classic short, simple riddle is that spoken by Samson, “out of the eater came something to eat; out of the strong came something sweet” (Judg 14:14). The narrative comment that follows is delightful: “for three days they could not explain the riddle”!

Another example is the proverb quoted by two prophets, about the impact of the Exile: “the parents have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge” (Jer 31:29; Ezek 18:2). The point of this saying is clear and telling. Likewise, the point is conveyed directly when Hosea laments the rebellion of the people, describing them as “like a dove, silly and without sense”, and noting how the Lord will discipline them; “I will cast my net over them; I will bring them down like birds of the air” (Hos 7:11–12).

This is the classic form of a comparison, a mashal, in which one item is compared with another item. A parable, at its heart, is a comparison: “this is like that”.

There are also more extended parables, with multiple characters and an extended storyline, such as in the parable that Nathan tells David in 2 Sam 12. Often, the simple comparison that is intended is developed into an allegorical tale. In an allegory, particular individual features can play an independently figurative role, so that the story told becomes a kind of riddle which invites a response from the listener. “What do you think?” becomes the implied way that the allegory-riddle ends. Listening to the story is not enough—the listener needs to engage, enter the conundrum, make up their mind!

In Hebrew Scripture, the allegory of the Eagles and the Vine (Ezek 17:3–10) is described as both ḥidah (“riddle”) and mashal. The parable first describes “a great eagle, with great wings and long pinions”, who carried seed far away where it took root and became a vine (a classic symbol of Israel). It then offers a further description of “another great eagle, with great wings and much plumage”, which the teller of the parable fears may seek to uproot the vine. “When it is transplanted, will it thrive”, the parable ends (v.10)—will Israel, transplanted into exile, manage to survive that experience?

Further parable-riddles occur in subsequent chapters in Ezekiel. There is the Lamenting of the Lioness (Ezek 19:2–9) and the Transplanted Vine (Ezek 19:10–14), and the stories of the Harlot Sisters (ibid. 23:2–21). There is also one of my favourites, the very vivid—and gruesome—parable of the Cooking-Pot (Ezek 24:3b—5).

In this parable, the prophet warns the people of judgement: “set on the pot … pour in water … put in the pieces, the thigh and the shoulder … fill it with choice bones” (that is, the meat and bones of the Israelites being punished). The prophet concludes with a booming denunciation: “woe to the bloody city … the blood is shed inside it … to rouse my wrath, I have placed the blood she shed on on a bare rock” (Ezek 24:6–8, and then the metaphor extended still further in 24:9–14).

Each of these parables are clearly allegorical, in that the overall point is clear, and yet also the details in the story invite connection with specific people or events. Ezekiel is a powerful speaker, who utilises this dramatic story-form with great flair, and effect. So, too, is Nathan, in the passage we hear this Sunday; the simple comparison is advanced through the story, in which various elements correlate with the situation involving David and Bathsheba.

For more on parables, see the links at the end of this post.

Nathan’s confronting story cuts to the heart of David. As the prophet declares, the king has acted in exactly the way that the man in the story has acted. He is privileged and well-to-do, and yet he seeks more through his selfish actions; there is pure evil in what he has done. Nathan berates David at length (2 Sam 12:7–10), climaxing with the warning of the Lord, “I will raise up trouble against you from within your own house” (12:11–12).

So David retreats from his anger and backs down in repentance: “I have sinned against the Lord”, he says to Nathan, who then reassures him, “now the Lord has put away your sin; you shall not die” (12:13). Nathan has executed his prophetic role with power: he speaks forth the word of the Lord into the immediate situation, calling David to account. At least the king recognises his sin and repents. God both punishes and forgives him.

Writing in With Love to the World, Sarah Williamson characterises this as “a classic revenge tale”. She notes that “David has ruined a family by killing Uriah and taking Bathsheba as his wife” and that “the prophet Nathan helps David see what he has done and as he comes to face his actions, he is told that his first born child will suffer the consequences.”

“This reflects the punitive nature of ancient Israelite thinking”, Sarah writes; and yet, “it is possible to understand this story with a different angle”. She explains: “It shows that, even though we may be ‘forgiven’, as was David for his actions, so our choices are not without consequence.”

This then raises questions to consider: “Could God deliberately harm a child for the actions of a parent? What sort of understanding do we have about the forgiveness of God? Is forgiveness free or does a price need to be paid?” Her reflection is that “our poor judgments can have a generational power; that which the parents do can affect the children and generations to come”.

And so she concludes that this reading may be “an invitation to reflect on our own theology of forgiveness and the consequences of our actions. Perhaps we may invite the notion of grace into this space and ask, what sort of a God do I see in this story, and how does it fit with my own faith?”

With Love to the World is a daily Bible reading resource, written and produced within the Uniting Church in Australia, following the Revised Common Lectionary. It offers Sunday worshippers the opportunity to prepare for hearing passages of scripture in the week leading to that day of worship. It seeks to foster “an informed faith” amongst the people of God.

You can subscribe on your phone or iPad via an App, for a subscription of $28 per year. Search for With Love to the World on the App Store, or UCA—With Love to the World on Google Play. For the hard copy resource, for just $28 for a year’s subscription, email Trevor at wlwuca@bigpond.com or phone +61 (2) 9747-1369.

The Jewish Virtual Library article on “Parable” can be found at https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/parable

For further reading on parables in the rabbinic tradition, see

Click to access rabinnic-parables.pdf

https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/11898-parable

https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2721/

See also