During Lent, the lectionary sets before us a string of passages that canvass key theological elements in the story of Israel. These stories, of course, also resonate also with the story of Jesus and his followers (and that is largely why they have been selected, I assume). We begin this coming Sunday with the promise of the land (Deut 26), and then follows passages focussed on the covenant with Israel (Gen 15), the provisions of God for the people (Isa 55), the renewing moment at Gilgal (Josh 5), the promise of “a new thing” (Isa 43), and the gift of The Servant (Isa 50). It is a stirring and inspiring sequence!

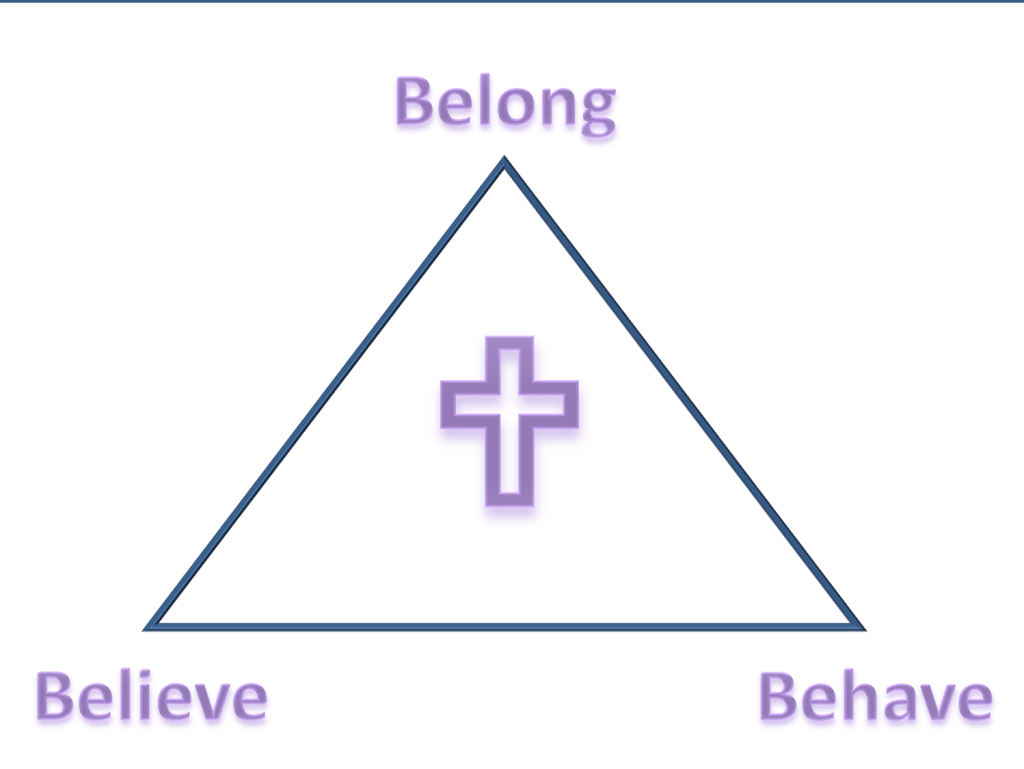

There is much debate amongst Christian thinkers, these days, about what comes first as we invite people to be a part of the church. Do we say, “this is what we believe, expressing our fundamental understanding of life; do you want to sign up to show you have the same beliefs?” Or do we say, “this is how we behave, guided by our fundamental ethical principles; would you like to act the same way and join us?” Or perhaps the invitation is simply, “come along, join in with us, see what we believe, what we are on about, and soon you’ll feel like you belong”?

Is it believe first? Or behave? Or simply, belong? The tendency to put a creed at the forefront of our invitations—to show that we are a people who believe, first and foremost—is widespread and deeply ingrained. Whether it be affirming The Apostles Creed in baptism, or saying The Believer’s Prayer at conversion, or working out a new Mission Statement for the Congregation, giving priority to belief is a very familiar pattern for us. We tend to think that, whatever formula we are repeating, that is exactly what declares and confirms our identity as people of faith.

So it’s no surprise that when we read Deuteronomy 26 (the Hebrew Scripture passage in next Sunday’s lectionary), we gravitate to the middle part of the passage, and lay claim to what looks to be an early affirmation of faith that sets out the identity of the people of Israel: “A wandering Aramean was my ancestor; he went down into Egypt and lived there as an alien, few in number, and there he became a great nation, mighty and populous” (Deut 26:5). This affirmation seems to go right back to the start, affirming what sets the people of Israel apart as a distinctive entity.

This way of reading this passage gained influence from the analysis of Gerhard von Rad, a German scholar of the 20th century. Von Rad claimed that the credal statement in verses 5 following was most likely a formula much older than the era when the book of Deuteronomy was written. And the origins of this creed, he claims, most likely lay in ancient cultic remembrances of the origins of the people. The wandering Aramean (Jacob, grandson of Abraham of Aramn) and the time in Egypt (leading up to Moses) reflect those times of origin.

*****

But the whole of this “creed” is not actually a “statement of faith”. It is more a narrative that tells a story. Such was the way of the ancient world; central beliefs were not articulated in crisp propositional statements (for this is the way of the post-Enlightenment western world); rather, a story was told, in the course of which key events pointed to central affirmations for the people. The ancients were story-tellers, more concerned to tell the story than state the faith. This is the story of the people; it is their saga.

God is important in the story that is told, nevertheless. God is the one who “heard our voice and saw our affliction, our toil, and our oppression … who brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, with a terrifying display of power, and with signs and wonders” (26:7–8). The rescue of the people by their powerful God is central to the story. This, of course, if the story of the Exodus, which stands at the heart of Israelite identity and later Jewish identity. It is the central story of the people of Israel.

More than this, God is the one who “brought us into this place and gave us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey” (26:9). The land of Israel is the second aspect of ancient Israelite life that is central and fundamental; and so it continues to be, in the 20th and 21st centuries, in which the land of Israel has been one of the most contested pieces of land in the world.

The story is told, however, for a purpose. Not just to remember—although remembering is important, for it recurs as a regular refrain in the book of Deuteronomy (7:18: 8:2, 18: 9:7, 27; 11:2; 15:15; 16:12; 24:9, 18, 22; 25:17; 32:7). The story is told, also, to inculcate the ethos, the values, the very identity of the people. And central to that ethos, taking prime place amongst the things that were seen to be important to affirm about who the people of Israel were, is this: giving back to God the first fruits produced by the land.

“So now I bring the first of the fruit of the ground that you, O LORD, have given me”, are the words that the people are to say, each time a harvest is produced. “You shall set it down before the LORD your God and bow down before the LORD your God”, the instruction declares (26:10). Gratitude is to the fore; gifting back the beginnings of “the fruit of the ground” to the God who gave the people the land to grow this fruit.

*****

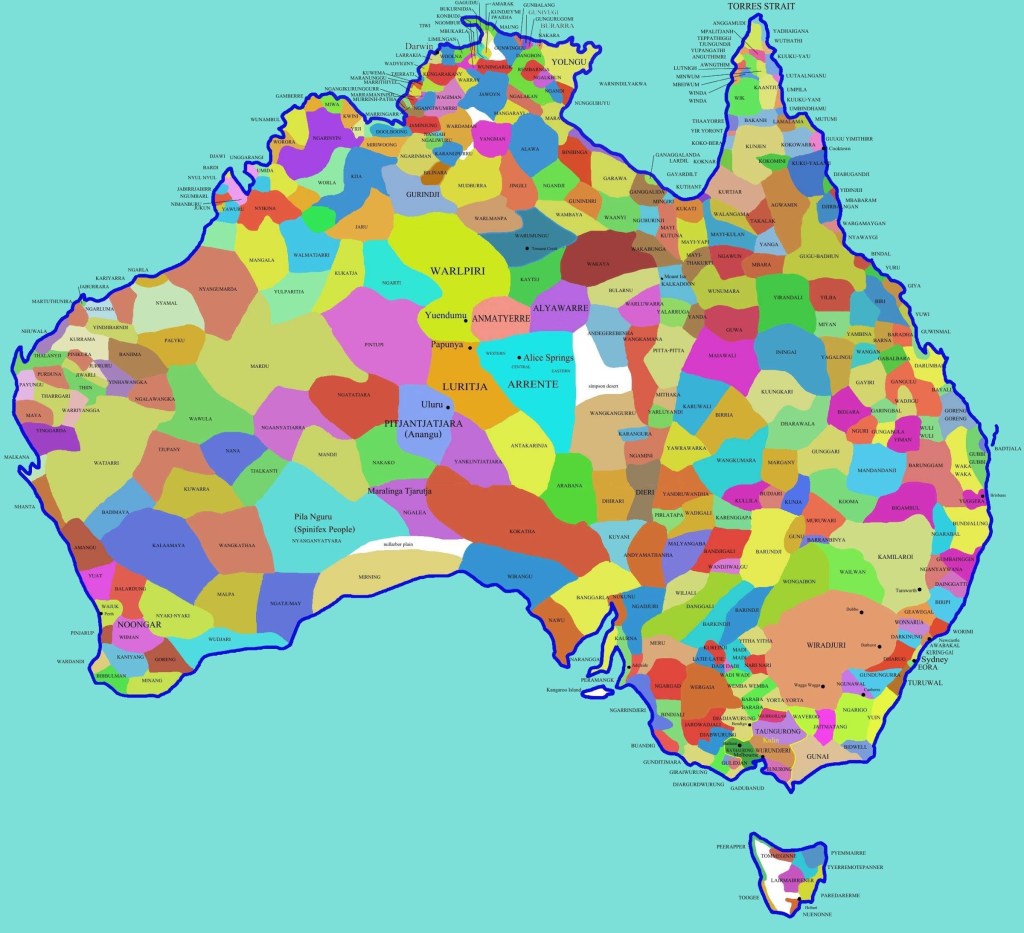

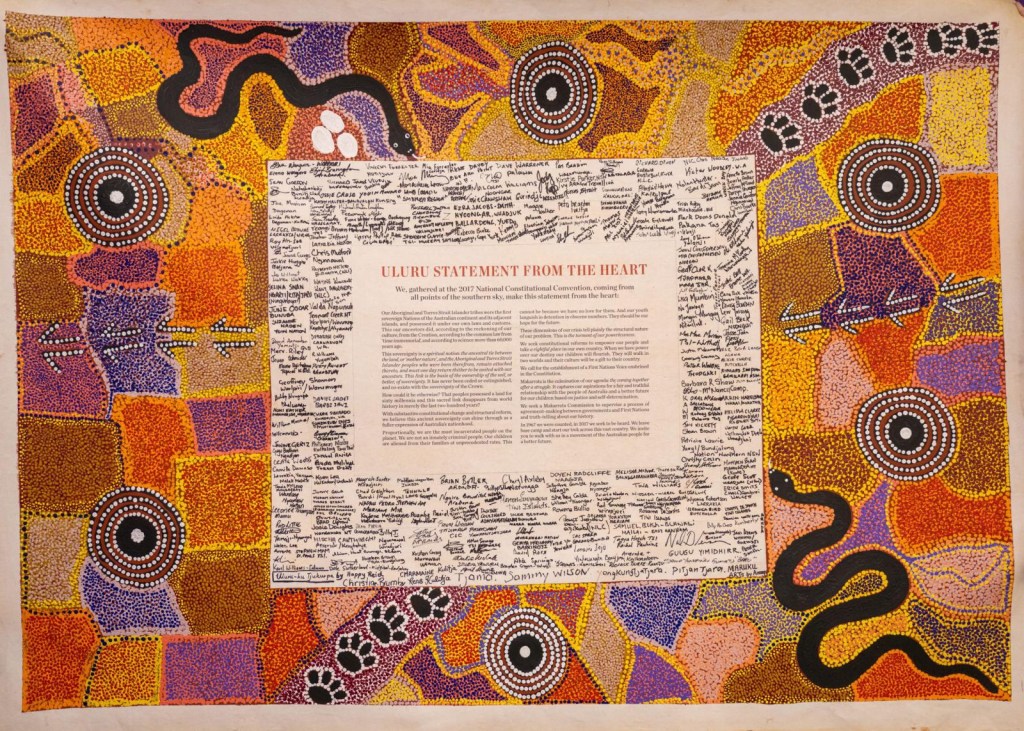

Of course, there is a dark story submerged, for the most part, underneath that celebratory action. The land was “given” by God over the resistance of the people who were already IN the land, producing fruit, settled and content with their lot in life. The battles recounted in the book of Joshua—most likely not actual historical events, but reflecting a reality of submission to the Hebrews who took control of the land—reflect this dark story.

This dark story does not figure in the “received tradition” and “authorised affirmation” that we read in Deut 26. Nor do we find this in the affirmation of Deut 6:20–24, which begins “we were Pharaoh’s slaves in Egypt, but the Lord brought us out …”. Mention of the Exodus jumps straight across to life in the land—no mention of the conquest that (in other biblical texts) is reported in detail.

This conquest is part, by contrast, of the larger recitation of Josh 24:2–13, “I brought you out of Egypt … and I handed the Amorites over to you, and you took possession of their land, and I destroyed them before you … and also the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Girgashites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites; and I handed them over to you … I gave you a land on which you had not labored, and towns that you had not built, and you live in them; you eat the fruit of vineyards and oliveyards that you did not plant.” At least this version of the affirmation is honest about the cost to the earlier inhabitants, and the benefits enjoyed with relative ease by the invading Hebrews.

*****

Yet the affirmation of Deut 26 highlights the central importance of gratitude for the gift of the land; and not only that, for it especially indicates the importance of making this celebration inclusive: “you, together with the Levites and the aliens [or, sojourners] who reside among you, shall celebrate with all the bounty that the LORD your God has given to you and to your house” (26:11). So the instructions for the annual festival of the first fruits provide.

The inclusion of the aliens in this annual festival reflected a gracious openness to others in the developing people of Israel. These texts differ from the xenophobic antagonism of earlier texts, recounting the conquest of Israel. They reflect a later understanding of the identity of the people, as they were collated during and after the Exile, centuries after the formation of Israel. People designated as aliens (non-Israelites), sojourners in the land, were welcome to bring offerings to the Lord (Lev 22:18), to adhere to Israelite food prescriptions (Lev 17:12), to keep the Sabbath (Exod 20:8–11; 23:12), to have gleaning rights (Lev 23:22), and to join in the annual process of atonement (Lev 16:29–31; Num 15:29).

The foundational Passover narrative indicates that aliens, or sojourners, were able to join (under certain conditions) in the Passover celebrations (Exod 12:47–49); a second narrative (Num 9:14) is much less restrictive. Aliens were to be subject to the same laws regarding murder (Lev 24:17–22), able to have right of access to cities of refuge (Num 35:13–15), and indeed to enter into the covenant at the annual covenant renewal ceremony (Deut 29:10–13; see also 31:10–13). The voice of the alien even sounds appreciation for the Law: “I live as an alien in the land; do not hide your commandments from me” (Ps 119:19).

Because Israelites were once “an alien residing in the land” of Egypt, the people were instructed, “you shall not abhor any of the Edomites, for they are your kin; you shall not abhor any of the Egyptians” (Deut 23:7); by the third generation, the children of aliens “may be admitted to the assembly of the Lord” (Deut 23:8).

This meant that “the alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt: I am the LORD your God” (Lev 19:34; a similar affirmation is made at Num 15:14–16).

The principle of equality is clear: “you shall not deprive a resident alien or an orphan of justice; you shall not take a widow’s garment in pledge” (Deut 24:17; see also Jer 7:5–7; 23:5–7; Zech 7:9–10; Mal 3:5). The alien, or sojourner, deserves the same measure of justice as all residents of Israel.

Accordingly, amongst the curses at the end of Deuteronomy, we read, “cursed be anyone who deprives the alien, the orphan, and the widow of justice. All the people shall say, ‘Amen!'” (Deut 27:19). The curse outlines the negative consequences from not adhering to the positive principle of welcoming and including those sojourning for a time innIsrael, the “alien”. That is integral to the celebrations each year, when the harvest produces its fruit from the land.

Gratitude. Belonging. Celebration. Inclusion. All of this is embedded in the story; and all of this comes before believing, repeating doctrinal claims, affirming credal statements. We are a people of welcome, including, belonging. This much is embedded in the ancient Hebrew tradition. This much should be living, still, in Christianity today.

See also