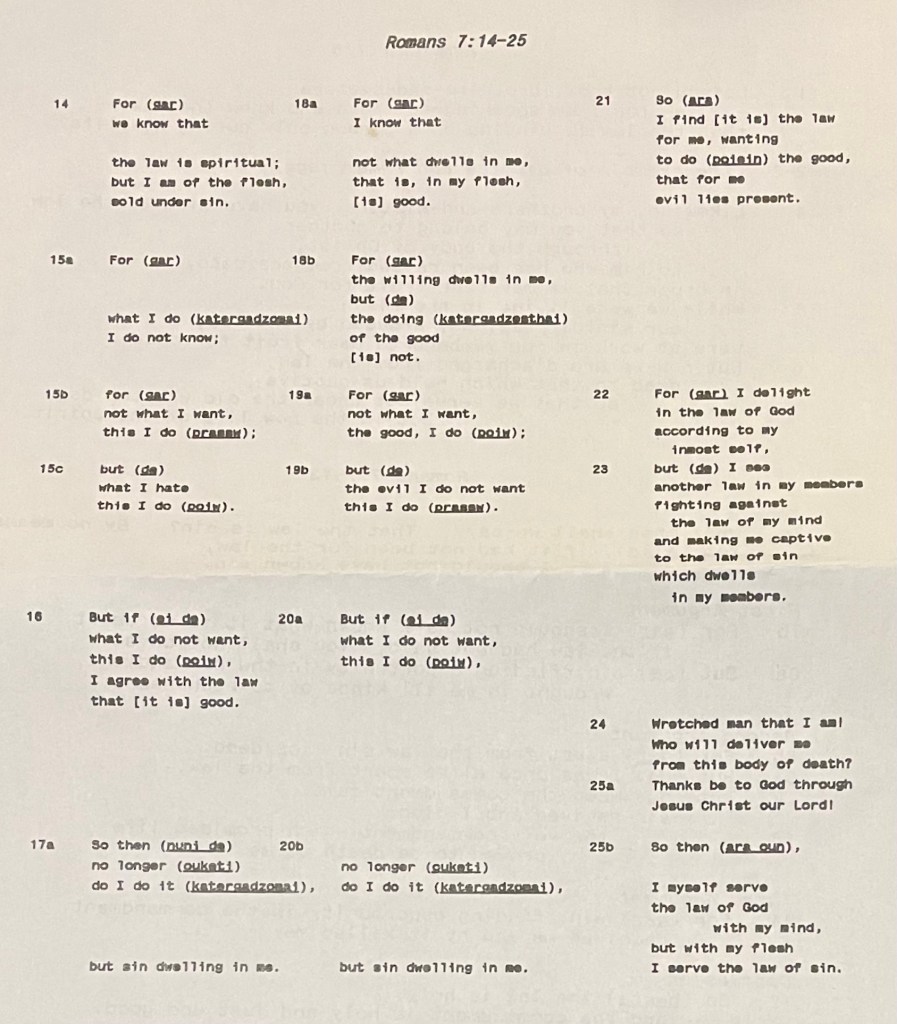

Last week, we considered the section of Paul’s letter to the Romans which the lectionary offered: Paul grappling within “the sin that lives within me” (Rom 7:14–25a). In probing that state, Paul came to a rather pessimistic conclusion: “wretched man that I am! who will rescue me from this body of death?” (7:24), before immediately switching to a grateful “thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!” (7:25). See

This week, the lectionary continues the argument that Paul is developing, as he presses on to rejoice that “there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (8:1). The passage proposed by the lectionary (8:1–11) marks a dramatic change in tone. Whilst he still recognises that “the mind that is set on the flesh is hostile to God; it does not submit to God’s law” (8:7), the primary focus that Paul now has is on the claim that “the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus has set you free from the law of sin and of death” (8:2).

Paul considers the state of humanity: “to set the mind on the flesh is death … the mind that is set on the flesh is hostile to God; it does not submit to God’s law—indeed it cannot, and those who are in the flesh cannot please God” (Rom 8:6–8). He has already grappled with this in the previous chapter. Here, he presses on to celebrate that, as he tells the believers in Rome, “you are not in the flesh; you are in the Spirit, since the Spirit of God dwells in you” (8:9).

Because of what the Spirit effects in the lives of believers, Paul is embued with great hope—a quality that he expresses in other letters he wrote. He rejoices with the Thessalonians that they share with him in “hope in our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Thess 1:3) and tells the Galatians that “through the Spirit, by faith, we eagerly waits for the hope of righteousness” (Gal 5:5).

He reminds the Corinthians that “faith, hope and love abide” (1 Cor 13:13), and then in a subsequent letter to believers in Corinth, he asserts that “he who rescued us from so deadly a peril will continue to secure us; on him we have set our hope that he will rescue us again” (2 Cor 1:10)

Paul has already reported to the Romans that “we boast in our hope of sharing the glory of God” (Rom 4:2) and that “we boast in our hope of sharing the glory of God” (5:2). He will go on to refer to “the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus” (8:2), and explain how the work of the Spirit gives hope to the whole creation, currently “in bondage to decay”, which will “obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God” (8:21). And so, Paul declares, it is “in hope that we were saved” (8:24).

Towards the end of the letter, Paul offers a blessing to the Romans: “may the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, so that you may abound in hope by the power of the Holy Spirit” (15:13). That the Spirit produces this hope is a fundamental dynamic in the process of “setting [believers] free from the law of sin and of death” (8:2).

The Spirit is rarely mentioned in the first seven chapters of this letter. Paul does note that it was “according to the spirit of holiness by resurrection from the dead” that Jesus was “declare to be Son of God with power” (1:4), and that it was “through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us” that “God’s love has been poured into our hearts” (5:5). And he notes that it was by being “discharged from the law” that believers entered into “the new life of the Spirit” (7:6).

But from 8:1 onwards, the Spirit becomes an active presence in what Paul writes about. The Greek word pneuma appears 33 times in the letter to the Romans; most of these are referring to the Holy Spirit. Strikingly, 19 of these occurrences are in chapter 8; a further eight instances then occur in chapters 9–15.

We might contrast this with the word that is often seen to be the key to this letter, dikaiosunē, which appears 57 times in Romans—including the programmatic key verse of 1:17, 13 times in ch.3, 11 times in ch.4, nine times in ch.5, and then nine more times in chs.9–11. Whilst righteousness is indeed an important word, the Spirit is also of crucial significance in Paul’s argument throughout Romans.

Rom 8:1–11 makes a strategic contribution to what Paul is explaining in this letter—that in the Gospel, “the righteousness of God is revealed through faith for faith” (1:17), that “the righteousness of God has been disclosed, and is attested by the law and the prophets, the righteousness of God through faith in [or of] Jesus Christ for all who believe” (3:21–22).

As he develops his argument, drawing on the story of Abraham (Gen 15), Paul affirms that this righteousness “will be reckoned to us who believe in him who raised Jesus our Lord from the dead, who was handed over to death for our trespasses and was raised for our justification” (4:24–25), concluding that “since we have been made righteous by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ” (5:1), and asserting that “if Christ is in you … the Spirit is life because of righteousness” (8:10).

Incidentally, when we look at the statistics of word occurrences in the seven authentic letters of Paul, we see that “righteousness” occurs a total of 87 times (57 of them in Romans, 13 in Galatians), whilst “spirit” can be found 117 times: as well as the 33 times in Romans, there are 39 occurrences in 1 Corinthians and a further 15 occurrences in 2 Corinthians, and then 19 more appearances in Galatians. Spirit is a fundamental component in Paul’s theology.

Paul believes that it is by the Spirit that the gift of righteousness is enlivened and activated within the believer. He hammers this point with a series of clear affirmations in this week’s passage (8:1–11): “there is no condemnation” (v.1), “the law of the Spirit has set me free” (v.2), “God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do: by sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh, and to deal with sin” (v.3), “the Spirit of God dwells in you” (v.9), “the Spirit is life” (v.10), and “he who raised Christ from the dead will give life to your mortal bodies also through his Spirit that dwells in you” (v.11).

Important for Paul is for the believer to know that “you are in the Spirit, since the Spirit of God dwells in you” (8:9) and that “his Spirit … dwells in you” (8:11). This is an idea that Paul also articulates in his first letter to a Corinth, when he poses the rhetorical question, “do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?” (1 Cor 3:16). The answer to this rhetorical question which is expected (but not stated) is, of course, “yes, we do know that God’s Spirit dwells in us”.

A similar rhetorical strategy can be seen as Paul draws this section (Rom 8:1–11) to a close. He poses a matched pair of conditional possibilities: “if Christ is in you” (v.10), “if the Spirit dwells in you” (v.11). The possibility, in each case, is crystal clear: since Christ is in you, “the Spirit is life because of righteousness” (v.10), and since the Spirit dwells in you, “he who raised Christ from the dead will give life to your mortal bodies also through his Spirit that dwells in you” (8:11).

For Paul, then, the role of the Spirit in enlivening and energising the believer is crucial. That is the important contribution that this passage makes to Pauline theology, and to our understanding of the Christian life.

See also