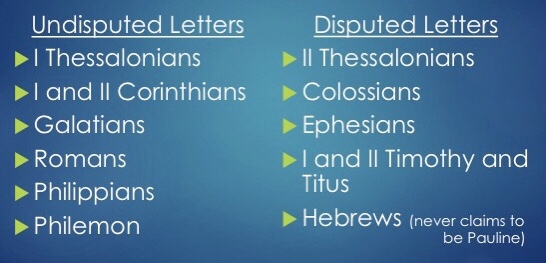

This coming Sunday, we turn from a letter written in the name of Paul, which few interpreters doubt is an authentic letter of Paul, to a slightly shorter letter which also claims to be written by Paul—but about which there is quite some debate as to whether Paul did write it. We will hear the opening section of the letter this Sunday (Col 1:1–14).

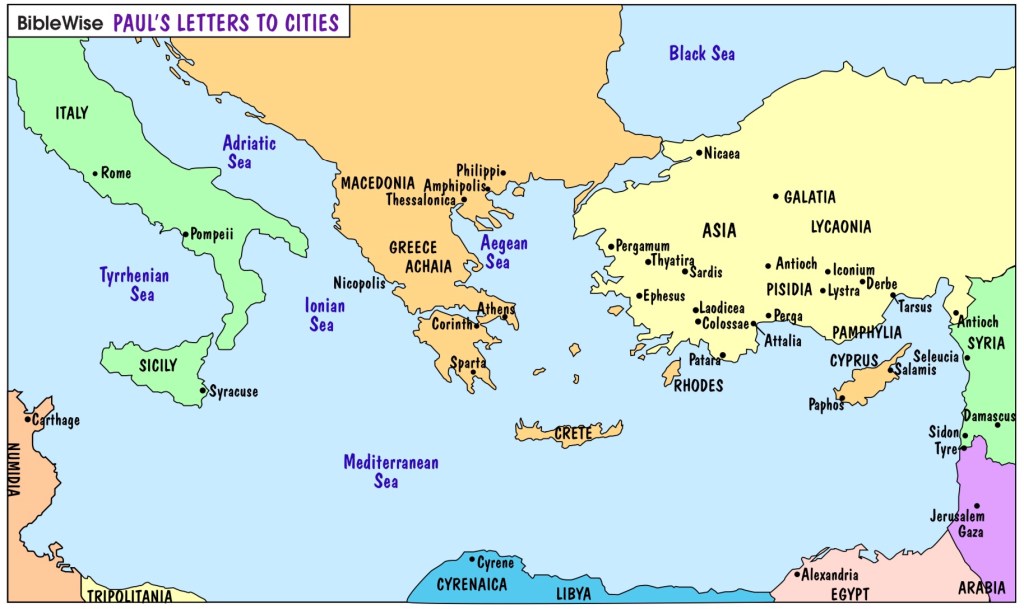

The letter begins with a clear claim to be a letter from “Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God, and Timothy our brother, to the saints and faithful brothers and sisters in Christ in Colossae” (Col 1:1-2). Despite this claim, there are signs that Paul may not be the author.

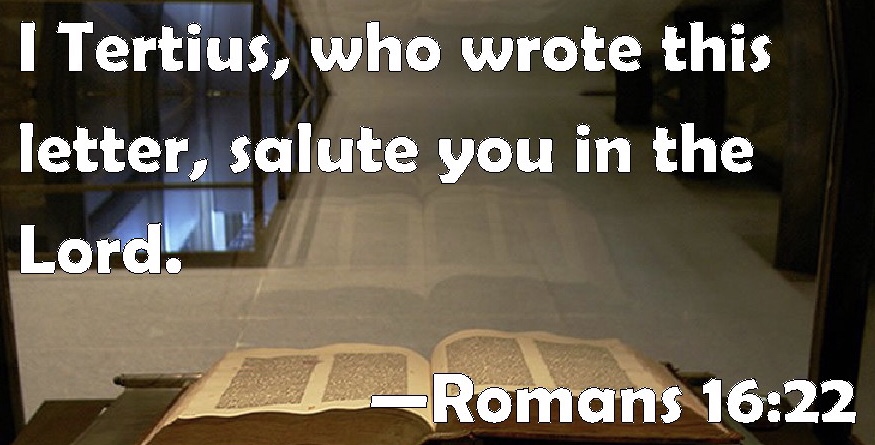

A more complex grammatical structure at some points, and some unusual vocabulary when compared with the vocabulary of the authentic letters of Paul, suggest a different hand in the creation of this letter. Some theological motifs are developed further than is found in the authentic letters of Paul, while the situation addressed appears to be different from—and probably later than—any situation envisaged in the lifetime of Paul.

(On the authorship of the various letters attributed to Paul, see https://johntsquires.com/2020/11/18/what-do-we-know-about-who-wrote-the-letters-attributed-to-paul-3/)

It is typical of Paul’s letters that the opening “prayer of thanksgiving” sets out some of the key contenders which will be addressed in the body of the letter. (This is the case in many other letters from the time that survive to today; whether Christian, or Jewish, or pagan, letters invariably flag key issues in the opening sentences.) Here, the key concerns seem to be about “the knowledge of God’s will in all spiritual wisdom and understanding” which will enable the readers and hearers of this letter to “lead lives worthy of the Lord” and “be prepared to endure everything with patience”.

The letter refers to Onesimus (Col 4:9), the slave about whom Paul wrote to Philemon (Phlm 10), as well as one of the addressees of that letter, Archippus (Col 4:17; Phlm 1). The greetings at the end of the letter contain a number of names also found in the greetings of Philemon 23–24: Epaphras (Col 4:12), Mark and Aristarchus (Col 4:10), and Demas and Luke (Col 4:14).

This suggests that the two letters might have originated at the same time in the ministry of Paul—when he was in prison (Col 4:3, 8; Phlm 10, 13), perhaps in Rome towards the end of his life. However, there is little else to connect Colossians with Philemon. The content of each letter is quite different.

Alternatively, the Colossian references to Paul’s imprisonment might link the letter with Philippians, written similarly during an imprisonment (Phil 1:7, 12– 14, 17). This would be so if Epaphroditus in Philippians (2:25; 4:18) was the same person as Paul’s associate, Epaphras, noted in Colossians (1:7–8; 4:12– 13). That possibility suggests a common origin; but no further links between these letters are evident.

A more fruitful connection is found between Colossians and Ephesians, where there are a number of similarities in theological development as well as a significant overlap of text. Eph 6:21b–22 replicates almost exactly the underlined phrases in Col 4:7–9. The most persuasive theory is that Ephesians, written well after the death of Paul by a follower of Paul’s teachings, drew on that section of Colossians, believing it to be the words of Paul.

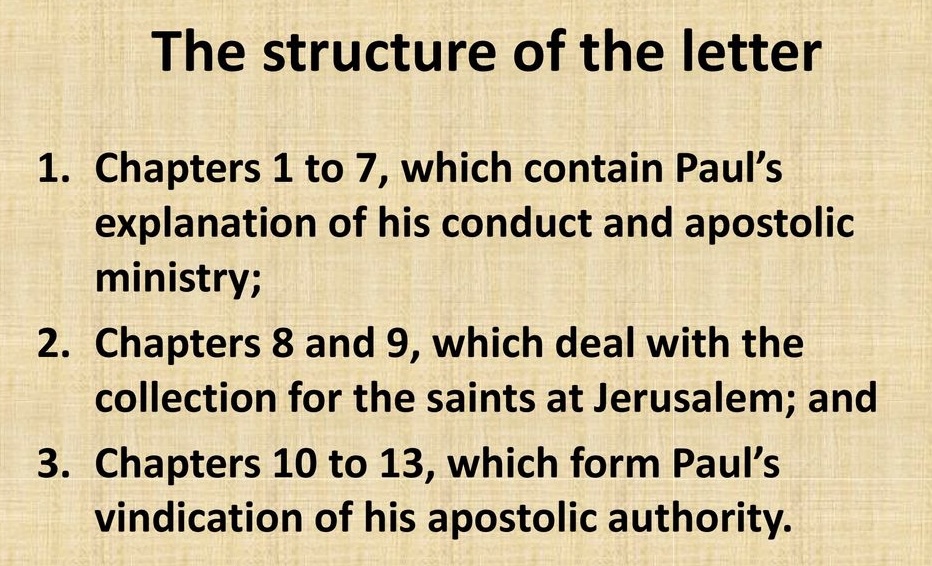

Returning to Colossians itself, we note that it follows the traditional form of a letter, with opening greetings (1:1–2) and thanksgiving (1:3–8) leading into a further prayer for the Colossians (1:9–14) before the body of the letter (1:15–2:23) and a series of exhortations (3:1–4:6). The closing greetings (4:7–17) and grace (4:18) bring the letter to a close in conventional fashion.

There are a number of indications of the distinctive situation to which the letter is addressed, although these insights are mediated through the perspective of the writer of the letter. The Colossians, although believers in Christ, continue to recognise the “elemental spirits of the universe” (2:8, 20). They are “deceived with plausible arguments” (2:4) and thus are captive to a “philosophy and empty deceit” (2:8) which is contradictory to Christian belief. They take part in “festivals … new moons … sabbaths” (2:16), engage in “self-abasement and worship of angels” (2:18) and adhere to strict regulations (2:20–22).

These terms seem to be describing people who are Gentiles (elemental spirits) who have adopted some Jewish practices (new moons, sabbaths, worship of angels) yet have an ascetic flavour (self-a basement) with rhetorical interests (plausible arguments) mediated through their philosophical interests. That’s quite a thick description of the presumed recipients, and not like others who received authentic letters from Paul.

Along with clear evidence for syncretism amongst the Colossians, there is a thought that the believers in Colossae were proto-Gnostics—that is, precursors of the kind of Christianity that emerged fully in the second century onwards, and which we know about most directly through the documents collected in the Nag Hammadi library (discovered in Egypt in 1945). See http://gnosis.org/naghamm/nhl.html

Over against this cluster of beliefs, the letter-writer advocates the gospel, which is described as “the word of truth” (1:5) and “the faith” (1:23; 2:7), and exhorts the readers to be “mature in Christ” (1:28; 4:12). The opening thanksgiving (1:9–10) contains key terms which express the writer’s hopes for the readers: understanding (2:2) and growth (2:19), and especially wisdom (1:28; 2:3, 23; 3:16; 4:5) and knowledge (2:2, 3; 3:10). These last terms, particularly, point in the direction of the developing Gnostic movement which held sway in some parts of the developing Jesus movement.

Some of these terms do appear in Paul’s authentic letters; some others appear less frequently, if at all. They do appear, however, in the Pastoral Epistles (written “in the name of Paul” some decades after his death) and then in various documents, not part of the New Testament, which demonstrate the growing Gnostic and speculative-philosophical tendencies in some parts of Christianity in the late first century and on into the second and third centuries.

The positive qualities which are highlighted in this letter, noted above, are especially related to Christ, in whom “the whole fullness of deity dwells” (2:9–10), a doctrine which sits at the core of a distinctive hymn in which Christ is portrayed as an all-encompassing cosmic figure (1:15–20). This is one key point where the letter moves beyond what is found in Paul’s authentic letters to the formulation of a post-Pauline doctrine. This, it seems, is central to “the word of truth” that is highlighted from the start of the letter.

My own conclusion is that Colossians was most likely written by a follower of Paul, writing in his teacher’s name in order to claim his authority as he addressed a situation different from, and some time after, Paul’s own time. Paul’s theological and ethical positions are known by the author. However, the problematic situation addressed, the theological ideas expressed, and the ethical instructions offered, each point to an origin after the lifetime of Paul.