Over its lifetime, the United Nations has been proactive in identifying issues of concern in the world and designating specific “days of” and “weeks of”: World Environment Day, World AIDS Day, World Mental Health Day, World Diabetes Day, World Poetry Day, Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, Interfaith Harmony Week, World Immunization Week, World Space Week, and more …

Today, 21 September, is one of those days: it is the International Day of Peace (Peace Day). This day was established in 1981 by a resolution of the United Nations resolution, supported unanimously by all representatives who voted. So Peace Day is a globally-shared date for all humanity to commit to Peace above all differences and work to ensure that Peace predominates over the conflicts raging in the world.

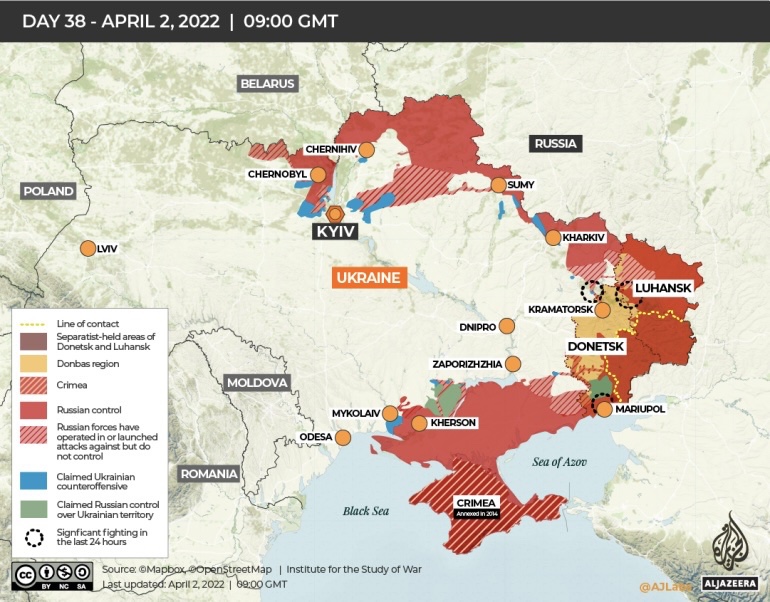

There is perhaps no more acute time, in 2025, for such a day to be highlighted. Our world today is beset by conflict, aggression, and devastating warfare. Mass starvation and the killing of civilians in Gaza; a genocide, many now (rightly) say. Decades of terrorist activity and the exercise of military power in Israel, the West Bank, Gaza, and surrounding nations. An entrenched military battle on many fronts in the Ukraine, bogged down in the ego of a long-term tyrant. Ethnic violence and long-enduring civil warfare in the Sudan. Armed uprisings in the Congo. A civil war in Myanmar following the 2021 military coup. The list could go on to cover many—far too many—places.

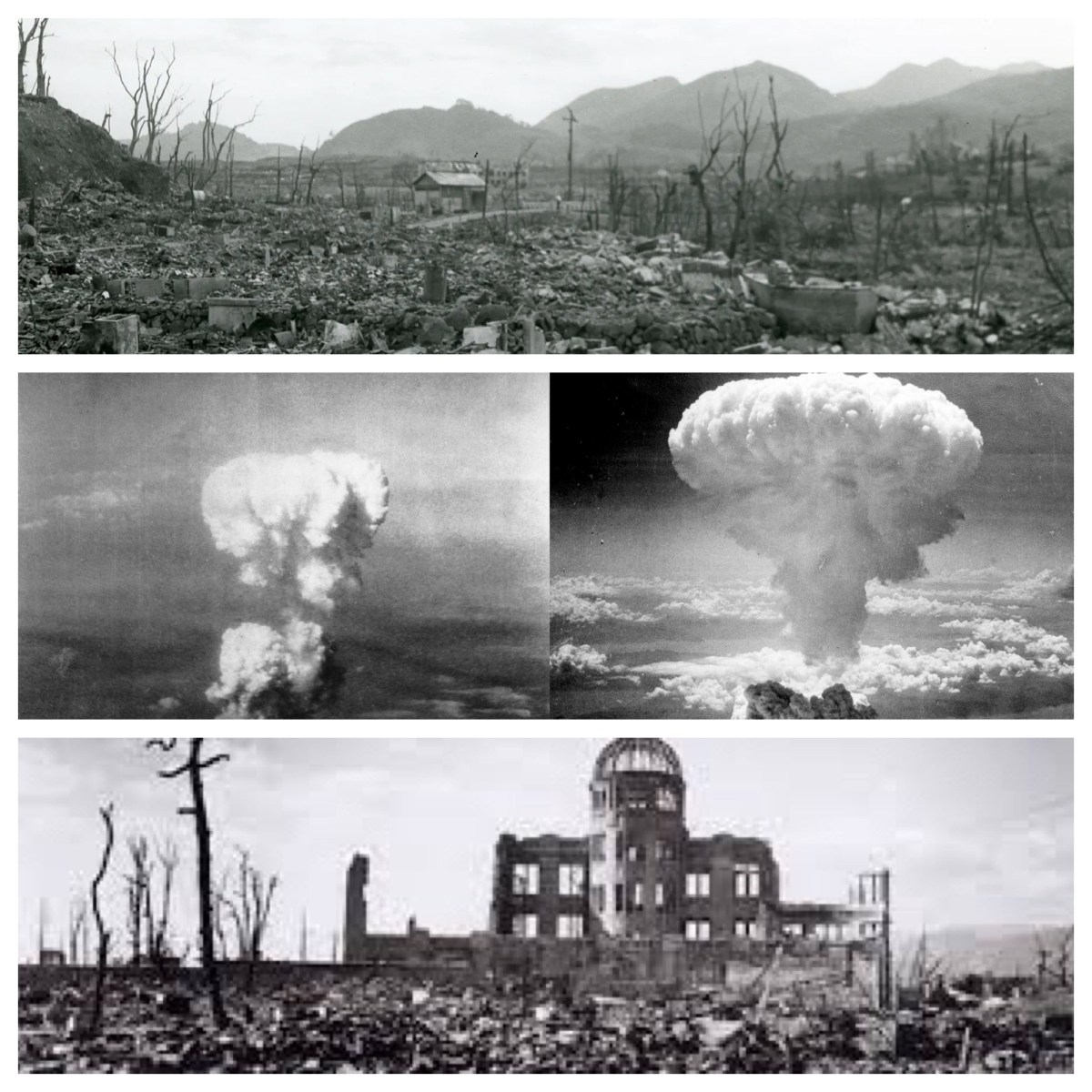

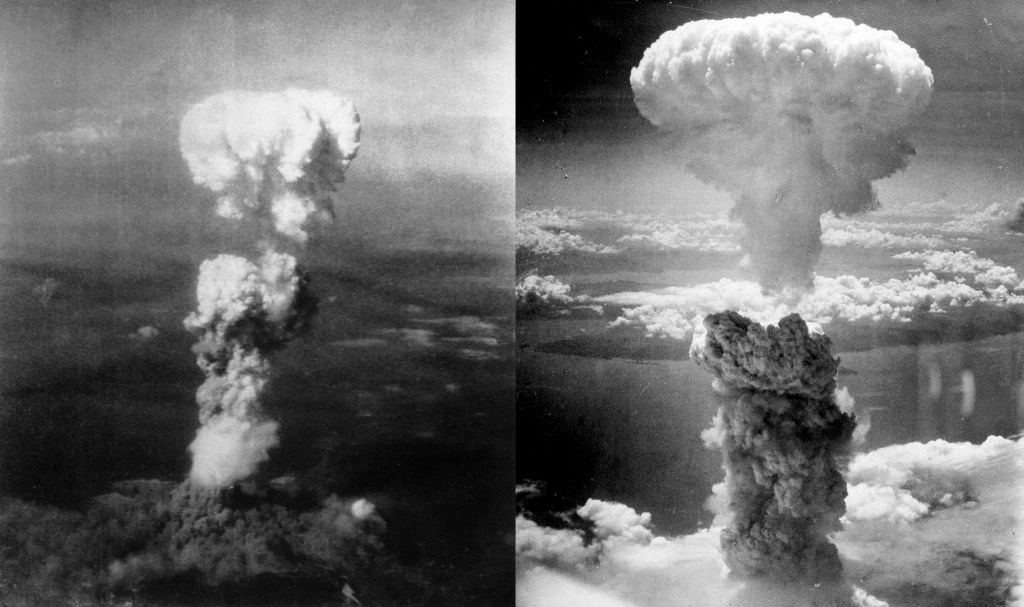

One of the myths of the 20th century is that there were two great wars (the two “World Wars”). That puts the focus on conflicts that involved many nations around the world, coalescing together in alliances to fight “the other side”. However, the terrible reality is that in every year of the 20th century, in country after country, Peace was absent. Civil wars, border disputes, regional conflicts, and terrorist insurgencies against unjust dictatorships, all attest to the continuing reality of the Lack of Peace around the world.

And at the moment, we really need some signs of Peace in our world. Where is Peace? When will it ever come? It is more important than ever that we recommit to seeking Peace in our world, and press our leaders to work towards peace in national life and International relations.

The theme for the 2025 International Day of Peace is Act Now for a Peaceful World. UN Secretary-General António Guterres has rightly said, “Around the world lives are being ripped apart, childhoods extinguished, and basic human dignity discarded, amidst the cruelty and degradations of war.”

Coinciding with the UN’s International Day of Peace is the World Week for Peace in Palestine and Israel, an event established by the World Council of Churches (WCC) and held each year during the third week of September. This year that week runs from Saturday 20 to Friday 26 September.

The week aims to encourage people of faith to pray for, and work towards, an end to Israeli oppression and allowing both Palestinians and Israelis to live in peace. A fine set of resources has been prepared by the WCC, containing testimonies, a Christian liturgy, a reflective poem, and a “concept note” that sets out the situation in Gaza, the focus of the week, and a set of steps that can be taken locally. See

https://www.oikoumene.org/events/WWPPI-2025?

The Uniting Church has long been a strong supporter of initiatives building towards Peace. Early in the life of the Uniting Church, the National Assembly made a clear and unequivocal commitment, on behalf of the whole church, to support peace-building and reject the idea that the world can be made a better place by killing people.

In 1982, that Assembly declared “that God came in the crucified and risen Christ to make peace; that he calls all Christians to be peacemakers, to save life, to heal and to love their neighbours. The call of Christ to make peace is the norm, and the onus of proof rests on any who resort to military force as a means of solving international disputes.”

It called for action “to interact and collaborate with local communities, secular movements, and people of other living faiths towards cultivating a culture of peace” and to work to “empower people who are systemically oppressed by violence, and to act in solidarity with all struggling for justice, peace, and the integrity of creation”. It also identified the need “to repent together for our complicity in violence, and to engage in theological reflection to overcome the spirit, logic, and practice of violence”.

Since the horrific attack on Israel by Hamas militants on 7 October 2023, and the devastating military retaliation by Israel in Gaza, the Uniting Church in Australia Assembly has sought to respond to a worsening conflict situation with a commitment to justice and peace. It has published a number of statements, which can be read at https://uniting.church/palestine-and-israel/

At the moment, the church is encouraging Uniting Church communities to take practical action on Palestine and engage with the World Council of Churches Statement on Palestine and Israel: A Call to End Apartheid, Occupation, and Impunity in Palestine and Israel. This statement has recently been affirmed and adopted by the Uniting Church Assembly.

In the statement, the WCC has declared that “the Government of Israel’s military campaign in Gaza has entailed grave breaches of the Fourth Geneva Convention which may constitute genocide and/or other crimes under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC)”. The WCC calls for churches “to witness, to speak out, and to act” in this matter.

*****

For more of my blogs on Peace, see

and see also

https://unitingforpeacewa.org/2018/11/28/perth-peacemaking-conference-statement/