The lectionary is currently offering sections from the latter chapters of the letter written by Paul and Sosthenes to “those who are sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints” (1 Cor 1:2). In the earlier chapters of the letter, the authors have canvassed a wide range of matters. First, they spend time addressing the serious divisions emerging within the Corinthian community. The letter notes that this matter “has been reported to me by Chloe’s people” (1:11); the singular suggests that Paul has already taken the primary role in writing this letter. It is thought that this must have been a verbal report passed on to Paul and Sosthenes when they met with a group from Corinth, perhaps slaves, sent by Chloe (about whom nothing else is revealed).

A second matter is introduced by a similar phrase, “it is actually reported…” (5:1), although the informant is not named. Some scholars think that the similarity of wording suggests that this news may also have been conveyed by “Chloe’s people”. A little later on, another matter is introduced with the phrase, “now concerning the matters about which you wrote” (7:1). Clearly, there had been written correspondence with Paul, at least, as well as the verbal report already indicated.

Towards the end of the letter, the authors refer to “the coming of Stephanas and Fortunatus and Achaichus” (16:17). This might suggest that they visited Paul and anyone else with him; a few verses later, there is the note that “Aquila and Prisca, together with the church in their house, greet you warmly in the Lord”, as well as “all the brothers and sisters” who send greetings (16:19–20).

Perhaps these three emissaries bore a letter from the community (or a section of it), asking for Paul’s opinions about these matters? The fact that their names are Roman names reflecting an educated status, would lend support to this hypothesis. Alongside this, we can also note that Paul personally concludes the letter by writing “I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand” (16:21). This suggests that a scribe—perhaps Sosthenes?—had actually been writing the letter to this point, most likely using pen and ink to commit the words dictated to them by Paul onto the papyrus. How much (or how little) the scribe would have had input into the letter is not clear.

Regardless of who actually brought this news, Paul and Sosthenes are willing to deal with the matters raised, introducing them in turn by the shorthand formula, “now concerning”. Such matters include “food sacrificed to idols” (8:1), “spiritual matters” (12:1), “the collection for the saints” (16:1), and “our brother Apollos” (16:12).

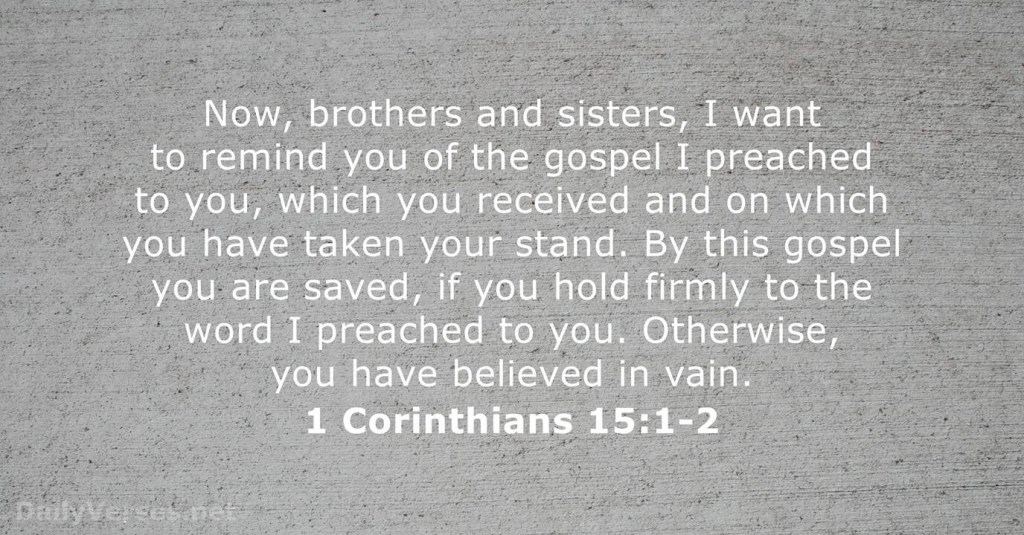

The final theological issue which they address in this first (extant) letter to the Corinthians, at quite some length, concerns the resurrection of believers. A rather strong formula is used to introduce a major theological issue at 15:1: “now I would remind you, brothers and sisters, of the good news that I proclaimed to you…”.

The letter considers this matter at length; many scholars regard it as the fundamental problem in the Corinthian community of faith, underlying other issues already explored. From comments later in this chapter (15:12, 15:29, and possibly 15:35), it is clear that divergent views about resurrection were held within the community of faith in Corinth. The response found in this chapter deals with each of them in a theological and rhetorical fashion.

Paul begins dealing with the issue with a series of affirmations concerning the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. There is an apologetic tone at the start, as Paul insistently underlines the validity and authority of what he says (15:1–3a). The “good news” which “I proclaimed” is described in technical terms indicating the passing-on of pre-existing tradition: “I received”, “I handed on”, “you received”. It is a matter of “first importance”.

Associated with this is an insistence that the Corinthians “stand” in this news, and must “hold firmly” to it, as the basis for “being saved”. The foundational tradition which is then reported (15:3b–7) is based on an early four-part affirmation of faith: “Christ died … he was buried … he was raised … he appeared …”.

The first and third elements are elaborated with the formulaic “in accordance with the scriptures”. The fourth element, the appearances of the risen Jesus, is extended beyond the list received by Paul (to Cephas, the twelve, more than 500, James, all the apostles; 15:5–7) to include Paul himself (“as to one untimely born”, 15:8), leading on to an assertion of Paul’s apostolic credentials and divinely-assisted activities (15:9–11).

All of this forms a solid foundation for the extended theological discussion that develops in the remainder of this chapter, as Paul explores various aspects of “the resurrection of the dead”. His personal experience of the risen Jesus presumably qualifies him, in his eyes, to develop the argument that unfolds.

This foundation reaches back to the “theology of the cross” at the start of the letter, where references to the crucifixion and death of Jesus provided a basis for the opening theological discussion of his letter (1:17–18, 22–25; 2:1–2, 7–10). However, Paul does not develop this connection beyond the opening 11 verses of chapter 15. Instead, he moves straight to a consideration of various pastoral situations in Corinth that have arisen regarding the resurrection (15:12–58).

The “resurrection of the dead” (the Greek word is plural, reflecting a raising of many believers) was a Jewish belief that had developed in preceding centuries; not all Jews accepted it (see Acts 23:6–8) and amongst some Gentiles there was scepticism about the idea (see Acts 17:32).

The community in Corinth contained sceptics (15:12); as a counter-argument to their scepticism the argument which is advanced in this chapter attempts to refute their opinion by setting out a series of logic-based steps. It begins by noting that people question the reality of the resurrection of the one person, Jesus (15:13–16). This leads to the accusation that “your faith is futile” (15:17). Paul and Sosthenes cannot countenance this, so they launch into an exposition of what they see as eschatological realities (15:20–28), explaining the places allocated, at the end, to humans, Jesus, and God.

Unfortunately, the lectionary omits these verses and jumps next week to v.35, where Paul raises questions which, he says, “someone will ask”, namely: “How are the dead raised? With what kind of body do they come?” In preparing to deal with these questions, Paul employs a rhetorical structure in the first part of this argument (15:21–22) which returns to the pattern of juxtaposing two different entities, which has already appeared in earlier sections of the letter.

We can see this pattern as follows:

for since death came through a human being / the resurrection of the dead has also come through a human being;

for as all die in Adam / so all will be made alive in Christ.

An expanded version of this argument takes place in Rom 5:12–21.

The argument countering Corinthian scepticism continues with an explanation that Christ is “the first fruits”, who has “all things put in subjection under his feet” (15:23–27). But Christ himself is subjected to God; finally, God is “all in all” (15:28). Paul has not proven the resurrection as such, but has explained how it fits into his view of the end days.

This deals with one factor in the Corinthian situation. There follows consideration of a second pastoral situation, raised through the question, “what will those people do who receive baptism on behalf of the dead?” (15:29). Paul abruptly dismisses this with two counter-punching rhetorical questions. First, “if the dead are not raised at all, why are people baptized on their behalf?” (v.29), inferring that such baptism could be completely ineffective. Second, “why are we putting ourselves in danger every hour?” (v.30), diverting attention to the claim that “I die every day!” (v.31). The clear inference is that there is no validity at all in the viewpoint held by those who practice “baptism on behalf of the dead”.

Then follows a poetic reflection (15:30–34) which includes sayings found in both Jewish and pagan sources, deployed to denounce those who “have no knowledge of God” (15:34). First, there is a reference to Hebrew scripture where the words “let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die” are found (Isa 22:13). In the context of the prophet, this saying refers to the sinners among “my beloved people” who are doomed for destruction (Isa 22:4) in the “day of tumult and trampling and confusion in the valley of vision” (Isa 22:5). Their fate is sealed; they can be only fatalistic.

The way it is used in 1 Cor 15, however, is that it conveys the nihilistic attitude of those who believe that “the dead are not raised”. They, too, exude a fatalistic attitude to life—perhaps echoing the fatalism of the Preacher, who reiterates the declaration that “there is nothing better for mortals than to eat and drink” (Eccles 2:24; 3: 3; 5:18; 8:15; 9:7), as befits his overarching view, “vanity of vanities … all is vanity” (Eccles 1:2; 12:8). This existential nihilism is where Paul places those in Corinth who refuse to accept the notion of resurrection.

Then, in 1 Cor 15:33, a saying is found in Greek poetry is quoted. The King James Version rendered this saying “evil communications corrupt good manners”, inclining us to understand that those who received these words from Paul were being warned to be careful with their words, for the constant repetition of an immoral saying might well,condemn a person to an immoral life.

However, the NRSV more accurately renders this saying as “bad company ruins good morals” (1 Cor 15:33); the Greek word here translated as “company” is homilia, which can simply mean communicating with someone, being associated with someone such as a close companion; or a more complex sense of exchanging intimate ideas, thoughts, and feelings through communion with another.

The words quoted are taken from the works of Menander, in a play called Thais which exists today in only a few small fragments. Thais was the companion of Ptolemy and held a powerful position in his court; in delivering a powerful speech to Alexander the Great during a drunken banquet, she convinced him to burn down the palace of Persepholis. (The story is told by Plutarch in his Life of Alexander book 38, and by Diodorus Siculus in his Universal History 17.72.)

Perhaps by quoting just a line from the play, Paul and Sosthenes were intending to evoke the scene of the drunken banquet at which Thais spoke. The affirmation that good morals are ruined by associating with bad company sits well with the licentious ethos conveyed by the saying “eat and drink, for tomorrow we die”. This is precisely the trap that some in Corinth have fallen into. So this section ends with the exhortation, “come to a sober and right mind, and sin no more” (15:34), and with the clear inference that, to their shame, there are some within the community who “have no knowledge of God”. Paul and Sosthenes are not willing to back down on their criticism of the Corinthians!

See also