1 Samuel 8:4–20 is the passage offered by the lectionary for this coming Sunday. It is the second in the sequence of Hebrew Scripture passages that we are reading through the first half of the long “season after Pentecost”, from May to August. The passage addresses an issue that was important in ancient Israel; that is important in modern-day Israel/Palestine; and that is important, also, in all nations around the world today.

This Sunday we will hear the beginning of a process—debate about having a king as a ruler—that culminates, at the end of August, with an account of Solomon, the wisest, most powerful, and perhaps most damaging king of all. That makes this ancient text potent in the contemporary situation, where Israel is engaged in a life- and-death struggle with Hamas, where megalomania amongst leaders in Russia, North Korea, China, and even the USA predominates, and where too many countries around the globe suffer under dictatorial, repressive regimes.

The passages selected today focus on the issue of power. Precisely: what kind of power in leadership is acceptable in Israel? should Israel be ruled by a king? For centuries, judges had led the people, determining what was right and what was wrong. The book of Judges tells of a string of such judges, men who worked hard to recall the people to their covenant with the Lord God: Othniel (Judg 3:9), Ehud (3:15), Shamgar (3:31), an unnamed prophet (6:8), Gideon (6:11–18), Tola (10:1), Jair (10:3), Jephthah (11:1; 12:7), Ibzan, Elon, and Abdon (12:8–15), and Samson (13:24–25; 16:28–31).

And, of course, it most famously tells of Deborah, “a prophetess, wife of Lappidoth, [who] was judging Israel; she used to sit under the palm of Deborah between Ramah and Bethel in the hill country of Ephraim; and the Israelites came up to her for judgment” (Judg 4:4–5).

However, the impact of the efforts of these various judges was merely transitory; the people returned again and again to their sinful, idolatrous ways. “The Israelites did what was evil in the sight of the Lord” (initially at 2:11, repeated at 3:7) is a recurring refrain throughout the book of Judges. It signals that the people reverted to their evil ways after Othniel (3:12), Shamgar (4:1), Deborah (6:1), Jair (9:6), and Abdon (13:1).

As a result, we are told that the people were “given into the hands” of their enemies on each of these occasions (3:8; 4:2; 6:1, 13; 10:7; 13:1). The horror perpetrated by Jephthah, offering his own daughter as a burnt offering (11:29–40), and the deceit and arrogance of Samson (16:1–31) exemplify this sinful streak.

In the final chapters of the book, details are given of the evil deeds of various people: the mother of Micah, who made an idol of cast metal (17:1–6); the men of Gibeah, who raped the Levite’s concubine (19:22–25); the Levite himself, who cut his concubine into twelve pieces (19:27–30); and then the attacks on the Bejaminites by the other tribes of Israel (20:1–48). The book draws to its end with the mournful conclusion, “in those days there was no king in Israel; all the people did what was right in their own eyes” (21:25).

So it is made clear in the narrative constructed in the book of Judges, that Israel’s downfall was that it was not ruled by a king, as other nations surrounding Israel were. A king could maintain justice and ensure equity within the society of Israel. And a king could marshal the forces needed to repel invaders and stand resolute against the sinful ways that would be imposed upon the nation by those who did not fear the Lord God.

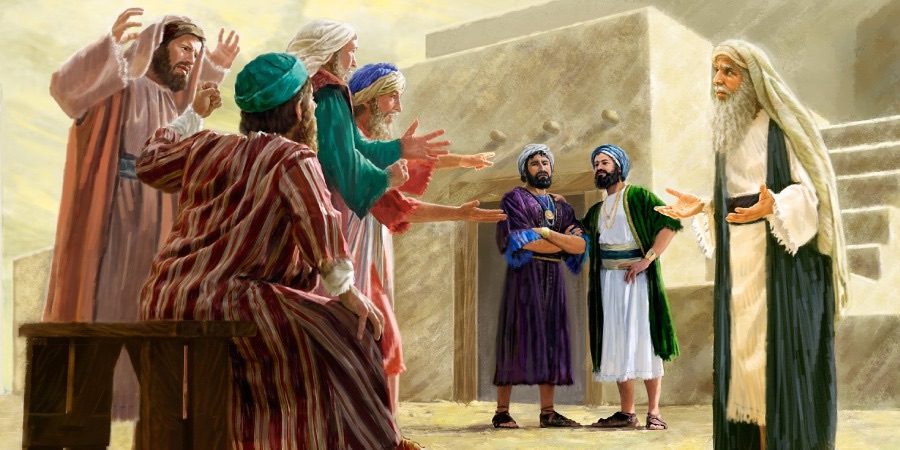

So the elders of Israel press for change; we can understand why. However, the prophet who has been called by God, Samuel, is attuned to God’s voice on this matter, and so he rejects this request. But the people persist with their request—their demand, even. And so it is that God, in a striking reversal of opinion, decides to have a change of mind about kingship. God pushes Samuel to accept this change.

The lectionary this coming Sunday offers us excerpts from the lengthy section of 1 Samuel where this matter is considered (1 Sam 8—11). The matter is first raised in the request made of Samuel by the people: “appoint for us, then, a king to govern us, like other nations” (1 Sam 8:5). The revolution comes, chapters later, after various points of view have been canvassed.

The lectionary selection for this Sunday offers us “A Dummies Guide to Kings in Israel”—that is, a series of “bites” [1 Samuel 8:4-11, (12-15), 16-20, (11:14-15)], some of which are optional (placed in parentheses). After the initial request, it includes the resistance of Samuel to this proposal (8:12–18) and the persistence of the people in pressing their request: “the people refused to listen to the voice of Samuel; they said “No! but we are determined to have a king over us” (8:19–20).

The full text of 1 Samuel provides reports of the back-and-forth that transpires, which the lectionary omits. It skips to a final optional reading of a further short section (11:14–15) which reports the outcome: “all the people went to Gilgal, and there they made Saul king before the Lord in Gilgal”.

The appointment of a king was obviously a matter of some controversy in ancient Israel; the compiler of the Deuteronomistic History (of which 1 Samuel is a part) devoted a significant amount of space to it, taking pains to include conflicting views about this matter. And, as we read these texts with the benefit of hindsight, we know that a king was ultimately appointed. This led to the later establishment of the Davidic dynasty, which became important in the claims later made about Jesus of Nazareth, recognised as Son of David.

So, of course, the person (or persons) chronicling the history of Israel in what scholars now call the Deuteronomistic history will tell the story with this outcome in view. The end result shapes how the story is told.

Writing in With Love to the World, Elizabeth Raine observes that “Israel looks for a leader to win battles and guarantee their security. It is a black-and-white understanding of the King; a figure military strength and political power. This is not the same as the way the prophet saw the role of King”. The people want power. The prophet warns of corruption. The people want victory. The prophet warns of failing to ensure justice.

And a clear thread in Hebrew Scripture would come to be that the king was called by God and anointed by God’s prophet to ensure that justice and righteousness were found in the land of Israel (Ps 72:1; 99:4; 1 Ki 3:28, 10:9; Isa 11:1–9; 32:1). That, at least, became the ideology for kingship in Israel; the reality, as we see in the stories selected for future weeks, was often different.

Elizabeth continues, “The story calls us to examine where we are placing our allegiances, and move to transformation, that process of repentance and renewal in which we turn back to God in every area. Whilst such self-examination is no doubt painful, it is also the only way to ensure we remain connected with God’s life-giving Spirit. As more and more people make the shift to a faithful allegiance that ensures that God’s Kingdom will be realised here on earth, we will hopefully see the reality of justice, peace, and love spreading in our world.”

To close, I offer two reflections on how this ancient story might speak to us today. The first perspective is that this story, about the desire for a powerful leader, and the dangers of pushing an agenda of power over all other matters, is a direct challenge to the way that the leaders of the modern state of Israel are conducting themselves in the long-enduring conflict with the Palestinians, who share an equally just claim to the land that was bequeathed to Jews in 1948. I have reflected at more length on this matter at

and my colleague Chris Budden has offered good insights into this conflict at

The second perspective is that this story is the first in a series of stories from ancient days which address a pressing contemporary issue: how to bring about effective change within the community of faith. It is something we all know about today, as society changes and the church occupies a different place in that society. How do we listen for God’s voice in this context? How do we advocate for effective change? I have written further on this dynamic at

and

With Love to the World is a daily Bible reading resource, written and produced within the Uniting Church in Australia, following the Revised Common Lectionary. It offers Sunday worshippers the opportunity to prepare for hearing passages of scripture in the week leading to that day of worship. It seeks to foster “an informed faith” amongst the people of God.