This coming Sunday, known as Palm Sunday, we will hear the story of Jesus, riding into Jerusalem, acclaimed by the crowds, for the festival of Passover. This year, we hear the story as it is told by Mark (Mark 11:1–11). It is a story which is well-known across the church, and is often re-enacted by children waving branches, adults singing songs—and sometimes a co-opted donkey—at this time of the year. It is a story which is often misinterpreted as portraying the gentle Jesus, meek and mild, receiving the accolades of the crowd with a beatific smile as he gently trots in to the city amidst the cheering crowd of pilgrims.

The actual story is far from that, however. If we read it carefully, we will find a number of indications that point us in quite a different direction entirely. There is no “gentle Jesus, meek and mild” in this story. Instead, we find a politically acute Jesus, provocatively and deliberately entering the city at the start of the important festival of Passover, with a clear message to the people of Israel and to the powers of Rome.

(The interpretation that follows is the result of careful exploration of the text in the context of Jewish and Roman history, that my wife Elizabeth and I have undertaken. See the end of the blog for more details.)

The political focus of Passover

The festival of Passover recalls the story that is told in the Hebrew Scriptures, about the exodus of Israel out of Egypt. This is a story of the liberation of an oppressed people, suffering under the burdens of forced labour. Every year throughout the centuries, Jews have recounted the sequence of events that led to the miraculous escape from slavery of their ancestors, crossing through the Sea of Reeds, travelling unhindered through the wilderness, towards a land which the story claims was promised by God—a promised land, gifted to a chosen people by a holy God (Exod 13–15).

Passover is therefore a political festival, recalling a central event in which the leader of a group of enslaved people confronted the leader of an oppressive power and gained liberation through divine intervention. In the time of Jesus, Jews from around the ancient world flocked to Jerusalem for this high moment of celebration, and the story was retold each year with notes of jubilation and joy.

During feast days, especially at each Passover, tensions reached fever pitch. Fervent Jews known as Zealots would use the opportunity of the many pilgrims in the city to mingle in the crowd with daggers hidden under their tunic—and take the opportunity to cause a commotion in the crowd, hoping that they could stab Roman soldiers, their dreaded enemy. The Romans increased their military presence to prevent open revolt. (See Josephus, Jewish War 2:255; Jewish Antiquities 20:186.)

So the Roman soldiers charged with keeping the peace in Jerusalem at Passover would therefore have been on high alert as the pilgrims entered the city. It is in this context that the story of Mark 11 takes place.

Riding on a donkey shows messianic intention

Jesus, seated on the colt, riding on a donkey, was the centre of attention—at least for his own followers (Mark 11:7). Those in the crowd who knew their scriptures, would have immediately recognised the allusion. What did this mean for observant Jews? First, Jesus was on a donkey, not a horse. Indeed, Jesus, as a faithful Jew, would never ride in triumph on a horse! See more at

The account of this story that we find in Matthew’s Gospel actually specifies the verse that interprets the significance of the donkey (Matt 21:4-5). Matthew refers to Zechariah 9:9, where a clear vision is offered: “your king comes to you, triumphant and victorious, humble and riding on a donkey”. And Zechariah himself may well have been referencing the moment when the young Solomon is summonsed to his father, the old king, David, and instructed to “ride on my own mule, and bring him down to Gihon” (1 Ki 1:33)—which Solomon duly does (1 Ki 1:38).

On his arrival, “the priest Zadok took the horn of oil from the tent and anointed Solomon. Then they blew the trumpet, and all the people said, “Long live King Solomon!” And all the people went up following him, playing on pipes and rejoicing with great joy, so that the earth quaked at their noise.” (1 Ki 1:39–40). Solomon’s journey on a mule is the journey to his accession to the throne. The resonances in the story about Jesus are clear.

That is what the reference to the words of the prophet evokes. In this story of Passover pilgrims, Jesus can be seen to be bringing the prophetic vision to fruition, as the fulfilment of the role that kingship plays in Israel. Zechariah’s vision declares that this coming ruler “shall command peace to the nations, and his dominion will be from sea to sea, from the river to the ends of the earth” (Zech 9:10). That is the vision that Jesus evokes as he rides into Jerusalem on this donkey.

The cries of the crowd evoke political resistance to Rome

The crowd sings out, “Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord” (Mark 11:9). The words were familiar words to observant Jews; they clearly evoke a well-known and oft-sung psalm, Psalm 118: “Save us, we beseech you, O Lord! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord” (Ps 118:25–26).

Why were they singing this psalm? Psalm 118 was one of the Hallel Psalms, the Praise Psalms, which were associated with celebrations on each of the three great festival days—the Feast of Tabernacles, or Booths; the Feast of Weeks, or Pentecost; and the Feast of Passover. These psalms of praise became particularly associated with the celebrations of the rebuilding of the Temple.

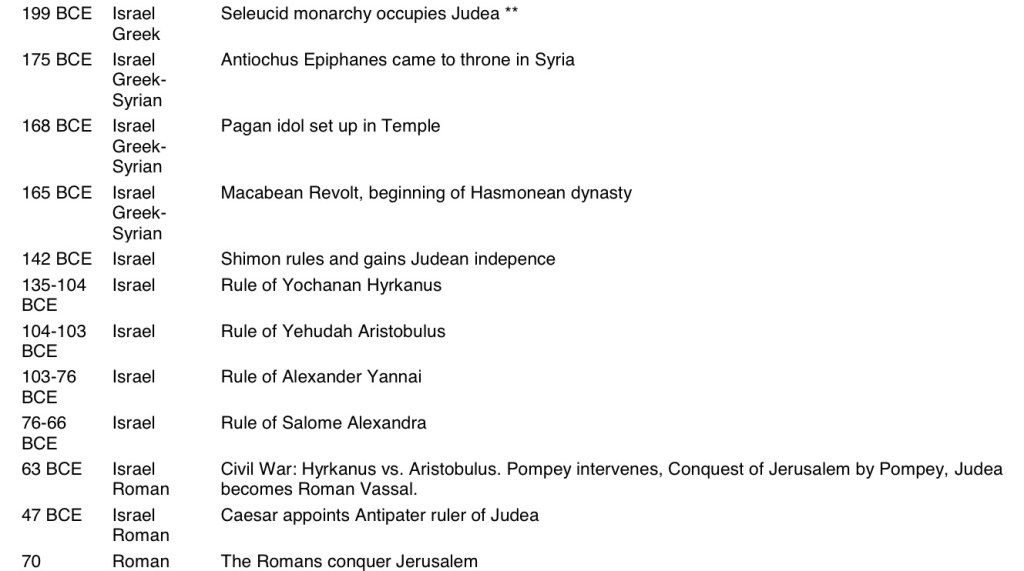

Rebuilding the Temple was an inherently political action. It was the foreign invasion of Palestine by the Hellenistic Seleucids some two centuries before Jesus which had led to the destruction of the Temple. It was the political activity of the Jewish Maccabees which had led to the reclaiming of the Temple two decades later.

The Hallel Psalms had become Psalms of Praise for liberating political activity. When the people cried out “hosanna”, a word from their native Hebrew language, they were crying “save us”. It is a cry for salvation; a yearning for deliverance. This is what the people were singing out; so the people singing this at the festival of Passover as Jesus entered the city was a strong political statement. See more at

The (palm) branches recall a political victory

This Sunday in the church year is traditionally called Palm Sunday. However, no palms are mentioned in the reading we have heard from Mark’s version of the story (nor in Matthew or Luke). That the branches are from palm trees is noted only in John’s version (John 12:13). Both Mark (11:8) and Matthew (21:8) refer to branches that the people cut and placed on the ground, even though they don’t specify that they are palm branches. (Nevertheless, waving palm branches has come to define this day—Palm Sunday—in contemporary re-enactments.)

This waving of palm branches was an activity intimately associated with the actions of the Maccabees, who were men from a priestly family who took up arms to fight back the Seleucid overlords and reclaim the Temple. The instructions in one of the Jewish books (2 Maccabees 10) direct the people to “carry ivy-wreathed wands and beautiful branches and fronds of palms, and offer hymns of thanksgiving to [God] who had given success to the purifying of their own holy place”. So the palms that are noted in John’s Gospel, at least, evoke the famous military campaign of centuries earlier.

The cloaks on the ground recall political leadership

Some people threw their cloaks over the donkey before Jesus sat on it—but Mark also notes that “many people spread their cloaks on the ground” (Mark 11:8). This is a curious detail; what can this mean? Perhaps the more astute of the Jews along the side of the road, would have had some insight; perhaps they recalled the story of the time when a young prophet from Ramoth-gilead declared that God was anointing Jehu, the son of Jehoshaphat, as the next king of Israel.

The story is recounted in 2 Kings 9, and it contains this striking detail, as the prophet decreed, “Thus says the Lord, ‘I anoint you king over Israel’”, and so they took their cloaks and spread them for him on the bare steps, and blew the trumpet, and proclaimed, ‘Jehu is King’” (2 Kings 9:13). There are clear resonances with the story of the Passover pilgrims. The cloaks on the steps, when Jehu is King … the cloaks on the wayside, when Jesus comes as King.

So Jesus, the prophet from Nazareth in Galilee, entered the city in the midst of the pilgrims, for the festival of Passover. Did he come as King, in the minds of the crowd? The festival of Passover was a most appropriate time for him to enter the city and make his mark as God’s chosen King. The donkey and the songs, the branches and the cloaks, all point to the immediate political significance of this event.

The incident in the temple sets the ball rolling

Once in the city, Jesus goes to the temple, where another famous incident occurs. Jesus, as he is portrayed in the striking account of this incident, demonstrates very little gracious, self-effacing humility. There is no “gentle Jesus, meek and mild” here, to be sure! Rather, Jesus is acting out his righteous anger, embodying zealous piety.

Jesus enters the temple precincts, overturning the tables of the money changers (Mark 11:15; Matt 21:12) and driving them out of the temple area (Mark 11:15; Matt 21:12; Luke 19:45). In John’s account, Jesus also tips out the coins of those money changers and knits together cords to form a whip (John 2:15), by which he drives out the moment changers. (Of course, John has completely relocated this scene to the beginning of the public activity of Jesus, rather than near its end, as in the Synoptic accounts of this scene).

Jesus was entering the area with intention and purpose. What was taking place there was, in his eyes, contrary to God’s will. So he performs a prophetic action designed to convey his message to those present (and to those of us in later times who hear and read the account of this incident).

James McGrath notes that “both the selling of animals for sacrifices and the payment of the temple tax were activities required by Jewish law and central to the temple’s functions” (see https://www.bibleodyssey.org/en/passages/main-articles/jesus-and-the-moneychangers). What Jesus does is therefore not an incidental act of anger; it is part of a deliberate plan of action.

McGrath suggests that the reference to the Temple as a marketplace might be an allusion to the eschatological prophecy of Zechariah, that “there shall no longer be traders in the house of the Lord of hosts on that day” (Zech 14:21). Is Jesus enacting this prophecy through his actions in the Temple forecourt?

Certainly, the actions of Jesus when “he would not allow anyone to carry anything through the temple” was confronting. He accuses the money changers of making the temple “a den of robbers” (Mark 11:17, Matt 21:13, and Luke 19:46). That most likely references the rhetorical question of the prophet Jeremiah: “Has this house, which is called by my name, become a den of robbers in your sight?” (Jer 7:11).

Gail O’Day considers that “by going to the Jerusalem temple and disrupting the practices that were necessary for the celebration of Passover, Jesus places himself in a long line of Israel’s prophets who go to Jerusalem, the center of religious and political power, and announce and enact the word of God.” (see https://www.bibleodyssey.org/en/passages/related-articles/cleansing-or-cursing)

In this dramatic prophetic action, Jesus acts and speaks carefully, deliberately, with “righteous anger”. He makes it clear what he is standing against, and what he is working towards—and he knows what the cost will be for him. After his dramatic entry into the city (Mark 11:1–11), he then presses on relentlessly into the temple (Mark 11:15–17), even symbolising his message in what he says to the fig tree: “may no one ever eat fruit from you again” (Mark 11:12–14).

Jesus knows exactly what he is doing. He has set in motion the events that will lead to his death: “when the chief priests and the scribes heard it, they kept looking for a way to kill him; for they were afraid of him” (Mark 11:18). His actions in the temple precincts were just as political as his entry into the city.

This is no “gentle Jesus, meek and mild”. This is a leader acting with a clear, focussed intent, regardless of the cost to himself and his followers. So this Palm Sunday, let us banish the Sunday School stereotype of Jesus, and acknowledge him in his full and fierce expression of his faith.

This blog on the Palm Sunday story is based on research by Elizabeth Raine and John Squires, published in Validating Violence—Violating Faith? Religion, Scripture and Violence. Edited by W. Emilsen & J.T. Squires, ATF Press, Adelaide 2008. See https://assembly.uca.org.au/rof/images/stories/interfaithsep/25sept.pdf

A version of this dialogue is also accessible at https://ruralreverend.blogspot.com/2019/04/palm-sunday-ps-1181-2-19-29-luke-1928.html