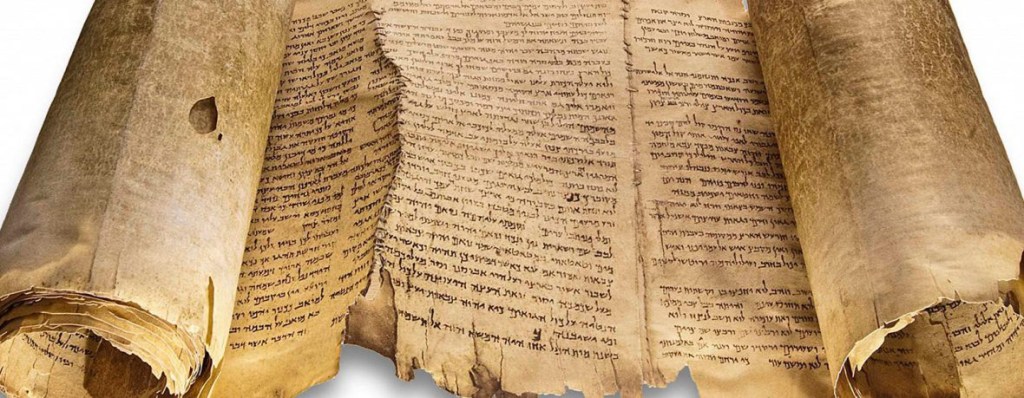

“Wisdom cries out in the street; in the squares she raises her voice; at the busiest corner she cries out; at the entrance of the city gates she speaks” (Prov 1:20–21). So begins the passage from Proverbs which the lectionary offers for this coming Sunday—the third passage from the “Wisdom Literature” that comprises much of the third section of the Hebrew TaNaK, the Kethuvim (“The Writings”).

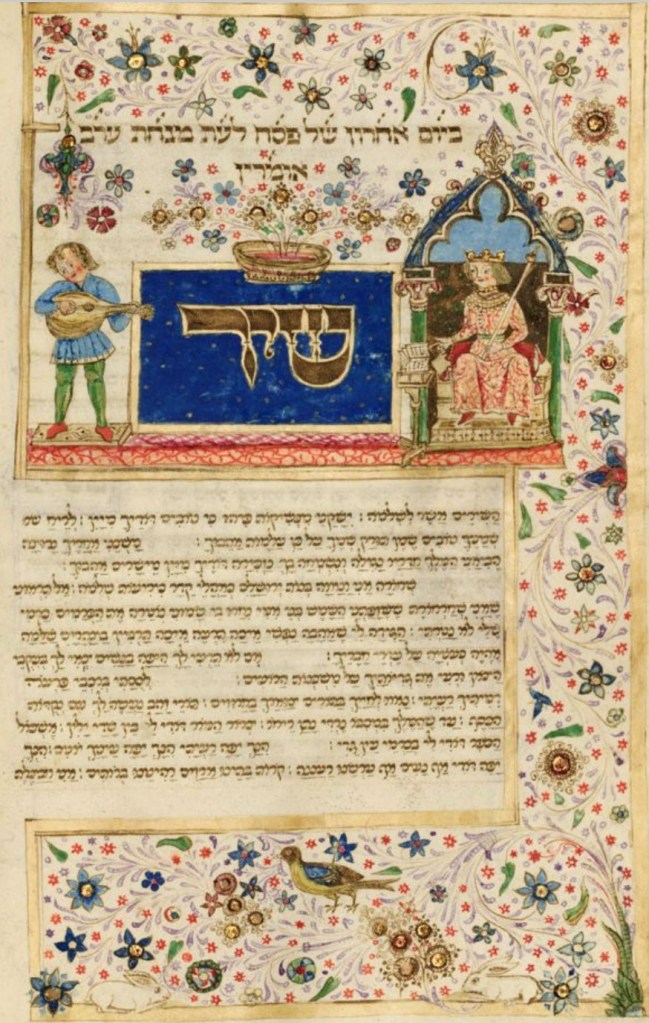

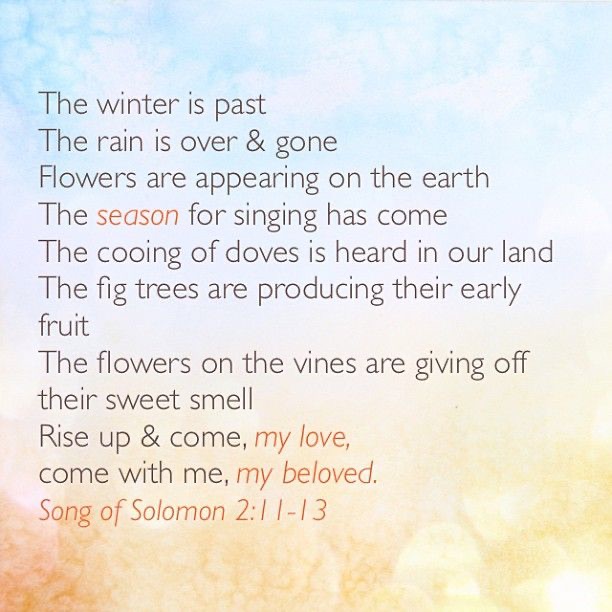

We saw two weeks ago, in the Song of Songs, that the woman singing some of the songs may have been functioning as the vehicle for communicating wisdom to the king, her lover. The passage this week, from the opening chapter of Proverbs, introduces us to the figure of Wisdom herself. She is positioned in a very public place “in the street” (1:20), a location which may perhaps be echoed by the woman in Song of Songs, who declares that “I will rise now and go about the city, in the streets and in the squares; I will seek him whom my soul loves” (Song 3:2).

Many occurrences of “the streets” in Hebrew Scripture depict scenes of terror and anguish, as the Lord God executes his judgement “in the streets” (Isa 5:25; 10:5-6; Jer 6:10-12; 44:6; Lam 2:21; Isa 51:20; and more). Nevertheless, the prophet Jeremiah is commissioned to proclaim his message in the pubic place of the streets (Jer 11:6) and the prophet Zechariah foresees the rejuvenation of the abandoned streets, when “old men and old women shall again sit in the streets of Jerusalem, each with staff in hand because of their great age; and the streets of the city shall be full of boys and girls playing in its streets” (Zech 8:4–5). The streets were clearly public places.

In Proverbs, Wisdom speaks out “in the squares” (Prov 1:20); this also is a public location which is echoed at Song 3:2. Again, Jeremiah is commissioned to “run to and fro through the streets of Jerusalem, look around and take note! Search its squares and see if you can find one person who acts justly and seeks truth” (Jer 5:1). Other prophets note the public significance of the squares. Amos foresees that because he has proclaimed the Lord’s message to “hate evil and love good, and establish justice in the gate … in all the squares there shall be wailing; and in all the streets they shall say, ‘Alas! alas!’” (Amos 5:15–16). Nahum portrays the invasion of Nineveh as being publically signalled as “chariots race madly through the streets, they rush to and fro through the squares” (Nah 2:4).

So Wisdom here in Proverbs—like the woman in the Song—is functioning in a very public place, as the opening couplet of v.20 indicates. The significance of this location is intensified when we consider the second couplet of the next verse: “at the busiest corner she cries out; at the entrance of the city gates she speaks” (Prov 1:21). The street corner may well have been the location for public prayer by some, if the words of Jesus reflect the common practice of “the hypocrites [who] love to stand and pray in the synagogues and at the street corners, so that they may be seen by others” (Matt 6:5).

However, it is the mention of “the entrance of the city gates” (Prov 1:21) that is most significant. The gates were part of the protective structure surrounding towns and cities; built into the walls at strategic locations, they could be opened to allow for the coming and going of traders and visitors, or they could be closed to keep out enemies and invaders. “Fortress towns” are described in Deut 3:5 as having “high walls, double gates, and bars”. King Asa decreed “let us build these cities, and surround them with walls and towers, gates and bars” (2 Chron 14:7).

In Jerusalem, the Chronicler claimed that it was the Levites who had responsibility for the gates, as Solomon appointed “gatekeepers in their divisions for the several gates” (2 Chron 8:14); their names, and their duties, are listed at length in 1 Chron 9:17–27. When the southern kingdom was under attack from the Assyrian king Sennacherib in 701, several towns in Judah were invaded (see 2 Kings 18–19; Micah 1:10–16).

Micah laments that “disaster has come down from the Lord to the gate of Jerusalem” (Micah 1:12); the wound inflicted on Judah “has reached to the gate of my people, to Jerusalem” (Micah 1:9). Some time later, the poet-author of Lamentations observes that “the kings of the earth did not believe, nor did any of the inhabitants of the world, that foe or enemy could enter the gates of Jerusalem” (Lam 4:12). The importance of the gates in providing security is clear.

In contrast, when Judith calls out to be let into the city, “the people of her town heard her voice, they hurried down to the town gate and summoned the elders of the town … they opened the gate and welcomed them, then they lit a fire to give light, and gathered around them” (Jud 13:12–13). Opening the gates is a clear sign of welcome to those acceptable to enter.

place of entry, a meeting place

Accordingly, the gates of the city became the place where various matters associated with the life of the city took place. When God’s angels arrived in Sodom, Lot was “sitting in the gateway,” apparently serving as a judge (Gen 19:1, 9). In association with the rape committed on Dinah, “Hamor and his son Shechem came to the gate of their city and spoke to the men of their city” (Gen 34:20). The “men of the city” are apparently often to be found in this location.

When David gathered his troops to fight against the uprising led by Absalom, “the king stood at the side of the gate, while all the army marched out by hundreds and by thousands” (2 Sam 18:4). After Absalom was killed, “the king got up and took his seat in the gate; the troops were all told, “See, the king is sitting in the gate”; and all the troops came before the king” (2 Sam 19:8). In a story from much later, Mordecai learned of plans to assassinate the king while “sitting at the king’s gate” (Esther 2:19).

Earlier in the narrative saga of Israel, when a soldier arrived at Shiloh and reported that Philistines had captured the ark of the covenant, Eli was sitting in the gate where “he had judged Israel forty years” (1 Sam 4:10–18). It was already known as a place for the judging of cases by the elders. That this took place at the city gates is clear from the story of Ruth, for Boaz went to the town gate to settle legal matters regarding his marriage to Ruth (Ruth 4:1–11).

Moses instructs Israel to “appoint judges and officials throughout your tribes, in all your gates that the Lord your God is giving you, and they shall render just decisions for the people” (Deut 16:18). Both the NRSV and the NIV render the phrase “in all your towns” as “in all your towns” on the reasonable understanding that each town has its own walls and gates.

Soon after this, one of the laws decrees that parents of a rebellious son who would not submit to their discipline were to “take hold of him and bring him out to the elders of his town at the gate of that place” and there “all the men of the town shall stone him to death; so you shall purge the evil from your midst” (Deut 21:18–21). Such was the nature of justice rendered “ at the gates”.

So finding Wisdom “at the entrance of the city gates” (Prov 1:21) is striking. This is the place where the men of the city would gather, debate, and render justice. In the normal course of events, women would not be found at the gates; their domain was inside the houses with their families. The psalmist sings, “your wife will be like a fruitful vine within your house” (Ps 128:3). Luke has Jesus indirectly indicate this when he tells his followers, “there is no one who has left house or wife or brothers or parents or children, for the sake of the kingdom of God, who will not get back very much more in this age, and in the age to come eternal life” (Luke 18:29). The wife, along with the rest of the family, is based in the house.

The acrostic poem at the end of the book of Proverbs (which will be our lectionary reading next week) clearly locates the “woman of valour” in the house, from daybreak, when “she rises while it is still night and provides food for her household and tasks for her servant-girls” (Prov 31:15), through the day as “she girds herself with strength, and makes her arms strong” (31:17) to complete the many tasks listed in this poem, right until the darkness comes, when “her lamp does not go out at night” (31:18b). See

The town gate was the place where business was conducted, and judgment according to law was enacted by men in the ancient Hebrew world. Monetary and legal transactions took place here in the presence of other men—the jtown elders—and it is here that the power plays of this male-dominated society took place. Women’s domain was in the privacy of their home, and any excursions into the public arena would usually be chaperoned by a family male member or older woman.

So the presence of Wisdom, not sequestered in the private space of the house, but rather by herself out in the public space, “in the street … in the squares … at the busiest corner … at the entrance of the city gates” (1:20–21), is quite noteworthy. The prominent biblical scholar, Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, has described Wisdom as “very unladylike, she raises her voice in public places and calls everyone who would hear her. She transgresses boundaries, celebrates life, and nourishes those who will become her friends.”

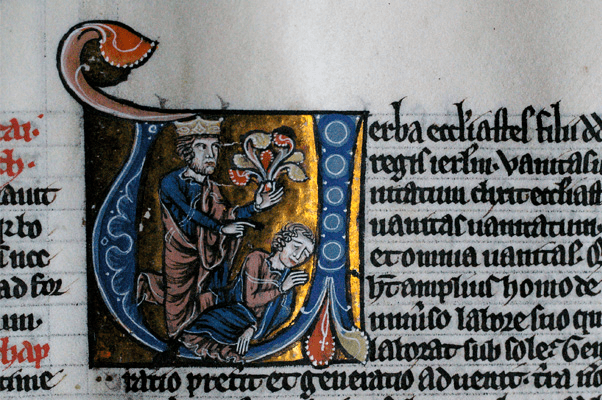

What does Wisdom do in this very public space? She cries out, berating the “simple ones”, demanding, “how long will you love being simple? … how long will scoffers delight in their scoffing and fools hate knowledge?” (1:22). These are strong words. Later, she describes how a “loud and wayward woman” used “smooth words” to seduce “a young man without sense”, one of “the simple ones” (7:6–27).

Like Wisdom, this woman is active in the public spaces, “now in the street, now in the squares, and at every corner she lies in wait” (7:12). Unlike Wisdom, who is “a tree of life to those who lay hold of her” (3:18), who offers “life to those who find them, and healing to all their flesh” (4:22), what this woman offers is “the way to Sheol, going down to the chambers of death” (7:27).

“Give heed to my reproof”, she continues; “I will pour out my thoughts to you; I will make my words known to you” (1:23). To the simple ones, she declares: “simple ones, learn prudence; acquire intelligence, you who lack it” (8:5). For too long, these scoffers “have ignored all my counsel and would have none of my reproof” (1:25, 30); they “hated knowledge and did not choose the fear of the Lord” (1:29). And so, she declares, “they shall eat the fruit of their way and be sated with their own devices” (1:31).

In like manner, one psalmist recognises that “those who carry out evil devices” shall “prosper in their way” in this life; but these people “shall be cut off, but those who wait for the Lord shall inherit the land” (Ps 37:7, 9), and so they implore the righteous person, “do not fret”, for “yet a little while, and the wicked will be no more … but the meek shall inherit the land, and delight themselves in abundant prosperity” (Ps 37:8, 10–11).

This is the faith that sits at the base of the Deuteronomic assertions about blessings and curses in this life, as “those who obey the Lord your God by diligently observing all his commandments and decrees” will indeed receive the blessing, for “the Lord will make you abound in prosperity, in the fruit of your womb, in the fruit of your livestock, and in the fruit of your ground in the land that the Lord swore to your ancestors to give you” (Deut 32:1–14), whilst those who will not so obey God will be afflicted with all manner of illness, pestilence, and destitution, and they “shall become an object of horror, a proverb, and a byword among all the peoples” (Deut 32:15–68; the extended list of curses and their impacts is indeed gruesome!).

Indeed, the wise words found in the book of Proverbs declare that “misfortune pursues sinners, but prosperity rewards the righteous” (Prov 13:21); Wisdom herself declares that “riches and honour are with me, enduring wealth and prosperity; my fruit is better than gold, even fine gold, and my yield than choice silver” (8:18–19).

These are the blessings for those who “walk in the way of righteousness, along the paths of justice” (8:20)—the very same righteousness and justice that is conveyed through the teaching of Solomon (1:1–3) and of Wisdom (2:9), the very same righteousness and justice which is “more acceptable to the Lord than sacrifice” (21:3).

This is the same righteousness and justice that the prophets have declared in the streets and on the corners of their society. Amos calls for “justice and righteousness” (Amos 5:22). Micah asks the question, “what does the Lord require of you but to do justice?” (Mic 6:8). Through the prophet Hosea, the Lord God promises to Israel, “I will take you for my wife in righteousness and in justice, in steadfast love, and in mercy” (Hos 2:19). Isaiah ends his famous love-song of of the vineyard by declaring that God “expected justice” (Isa 5:7).

In the exile, Ezekiel laments that “the sojourner suffers extortion in your midst; the fatherless and the widow are wronged in you” (Ezek 22:7). Jeremiah encourages the people of Jerusalem with a promise that God will allow them to continue to dwell in their land if they “do not oppress the sojourner, the fatherless, or the widow” (Jer 7:5–7). Second Isaiah foresees that the coming Servant “will bring forth justice to the nations” (Isa 42:1) and knows that God’s justice will be “a light to the peoples” (Isa 51:4).

Later, the words of Third Isaiah begin with a direct declaration, “maintain justice, and do what is right” (Isa 56:1); his mission is “to bring good news to the oppressed, to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and release to the prisoners” (Isa 61:1), thereby demonstrating that “I the Lord love justice” (Isa 62:8).

In teaching about Wisdom in the book of Proverbs, Elizabeth Raine has written: “Wisdom functions in the same way as the prophets, standing where prophets and teachers would have stood, at the city gates, a busy place where all manner of business was transacted. However, Wisdom does not cry out in the temples or synagogues, but rather in the public squares, the city gates, at the crossroads where people from all nations are gathered or are passing through.

“She declares that those who incline their minds to her spirit and follow her words in their lives will receive knowledge and wisdom. She also suggests that those who ignore this invitation will be punished, much as the prophets decreed that ignoring the commands they carried from God would also result in punishment.

“The main difference here is that Wisdom speaks these things in her own voice—there is no ‘thus says the Lord’ as we find in the prophets. She does mention ‘the fear of the Lord’, and those who do not choose this, who hate knowledge, will be left to their own devices, something that is presented as very undesirable and inviting calamity.”

Wisdom is indeed a strong, persuasive, significant figure in the Hebrew Scriptures.

You can read the full sermon by Elizabeth at