We continue exploring the readings from Acts that are offered by the lectionary in the session of Easter. The second main section of the second volume of Luke’s orderly account (8:1–12:25) outlines the steps taken by members of the Jerusalem community as they continue to fulfil the prophecy of Jesus (1:8), bearing witness to the good news as they move out from Jerusalem and Judaea to Samaria and beyond.

There are four main steps taken in this second section, recounting how selected community members begin to “turn to the Gentiles”, as Paul later describes it (13:46). These steps together form a pivotal moment in the narrative; they provide initial validation for the establishment of communities which are inclusive of both Jewish and gentile members. The readings for this Sunday include the narrative of one of these steps—the call and commissioning of Saul (Acts 9:1–6).

1 Turning to the Gentiles: four steps

The geography of this section (8:1–12:25) is structured in a spiral-like fashion, moving away from Jerusalem only to return to it before the next outwards movement occurs. In the first step (8:4–40), Philip enters the city of Samaria (8:5) but ends by returning to Caesarea (8:40). His actions in Samaria receive validation through a visit from the apostles in Jerusalem (8:14). The second step, concerning Saul (9:1–31), begins in Damascus (9:2) but returns to Jerusalem (9:26) before Saul leaves for Tarsus (9:30). This is the step that is in view in this Sunday’s lectionary offering.

The third step, focussed on Peter (9:32–11:18), begins in Judaea at Lydda (9:32) before moving through Joppa (9:36) to Caesarea (10:1). The action moves between Joppa and Caesarea before Peter returns to Jerusalem (11:2) and recounts what has taken place in Joppa and Caesarea to the Jerusalem community.

The final step (11:19–12:25) begins in Antioch (11:20), where the community receives envoys: Barnabas from Jerusalem (11:22) and Saul from Tarsus (11:25), followed by prophets from Jerusalem (11:27). The narrative then returns to Judaea (11:29–30) for the delivery of the “collection” and for an account of further events in Jerusalem. A brief visit to Tyre and Sidon (12:20) precedes the return of Barnabas and Saul to Jerusalem (12:25).

2 A pivotal figure: Saul of Tarsus

The second step in this section (9:1–31) recounts a key miracle: the complete turnaround of a persecutor, including his blinding and then restoration to sight, prior to his engagement in preaching activity amongst the messianic believers. The man who experienced this miracle has been introduced in passing at the point of Stephen’s death (7:58; 8:1a); the inference of this brevity may be that he was a character already well known to Luke’s audience.

At 9:1, the narrative returns to this individual, Saul. He will become the pre-eminent human character in the later narrative of Acts; for Luke, he will become the model par excellence of faithfulness in the face of opposition and persecution. So this is an account, not only of a conversion, but more than that (and most importantly, for a Luke), it is an account of the commissioning of this central figure, Saul.

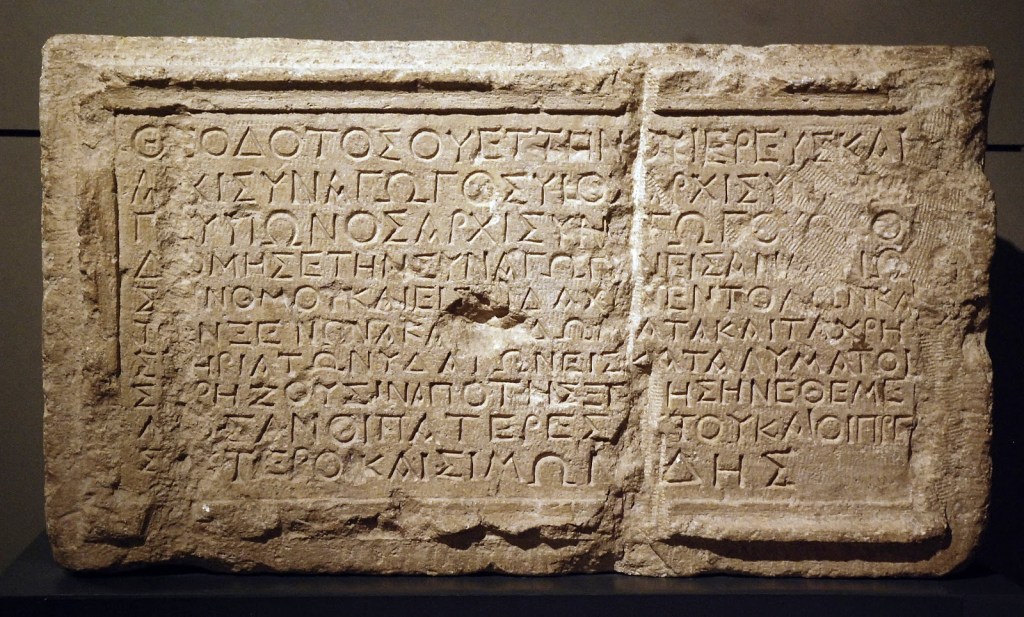

But at this moment in Luke’s orderly account, Saul is simply a vigorous persecutor of “the disciples of the Lord” (9:1). The account of his conversion and commissioning (9:1–19a) begins on the road to Damascus, a predominantly Jewish town in the Roman province of Syria. This location foreshadows the ultimate move into the Gentile world. Luke appears to assume knowledge that Damascus contains “disciples of the Lord” (9:1). How they got there is not narrated, nor whether they were Jewish or gentile disciples.

These disciples are described, for the first time, as being of “The Way” (9:2), a term which recurs in later chapters of Luke’s narrative (18:25; 19:9,23; 22:4; 24:14,22). On the importance of this term, see https://johntsquires.com/2022/04/26/people-of-the-way-acts-9-easter-3c/

By using the term “the Way” for the first time in his account of the conversion and call of Saul, Luke emphasises the Jewish characterisation of those communities which declare Jesus to be Messiah, even if they are in gentile areas.

3 The conversion of Saul

When Luke introduces Saul, he is described as a fearsome opponent of “the Way” (9:1). The Greek of this verse reads literally, “he breathes a murderous threat” (9:1; NRSV, “breathing threats and murder”), precisely the antagonistic threatening attitude about which the Jerusalem community has already prayed (4:29). Saul has gained his authority from the high priest (9:1), already identified as standing in opposition to God’s agents, Peter and John (4:6; 5:21,24) and Stephen (7:1).

Saul was previously described as being “in agreement with their plan” (8:1a). The scene is thus set for a continuation of the conflict narrated in Jerusalem; Luke’s description of Saul’s activities (9:2) imports this conflict to Damascus in tangible ways.

In letters written later by Saul (under the name of Paul), he refers to this period of his life as “violently persecuting” the believers (Gal 1:13; Phil 3:6). His own references to his change of heart, to become a member of the messianic assemblies, are brief and lack any of the narrative colour and detail that Luke’s accounts provide (Gal 1:15–16; Phil 3:7–11; 2 Cor 4:4–6; and possibly 1 Cor 9:1).

The crucial event which takes place as Saul draws near to Damascus is initiated by an epiphany: an overpowering light shines and a voice speaks to Saul (9:3–6). The epiphanies which have already taken place in Acts (1:10–11; 5:19; 8:26) are described in a rather bare fashion. By contrast, this particular epiphany is recounted in detail (as is the later epiphany to Peter, 10:10-16). The divine origin of the epiphany is promptly identified: the light was from heaven (9:3). The voice which addresses Saul is that of Jesus, whom Saul (as did Stephen before him, 7:59–60) addresses as “Lord” (9:4–5).

4 The Lord: an ambiguous term

At this point in the narrative, the ambiguity of the term “Lord” is heightened. Until now, the vast majority of occurrences of “Lord” have referred to God. From this point on, the term can be used to refer to Jesus (20 times, of which 4 repeat the incident from ch.9), although more often it still refers to God (36 times).

When Luke reports that people “turned to the Lord” (9:35; 11:21) or “believed in the Lord” (9:42; 11:17; 14:23; 16:15,31; 18:8; 20:21), the phrase appears somewhat ambiguous as to its precise referrent. However, in each case the context indicates that “the Lord” is now referring to Jesus.

The later categories of christological thought (after Nicaea) introduce categories not relevant for the time when Luke’s text was being written. The most that can be said is that Luke never envisages any ontological unity of Jesus and God, but on some occasions (and certainly not always) there is an overlap of function—Jesus now functions as God has functioned in the past.

For the most part, Luke presents Jesus as an agent of God’s sovereignty, as one member amongst many (Peter, Philip, Stephen, Saul, Barnabas, and so on), who have functioned as agents of God’s sovereignty. Occasionally, Jesus is distinguished from these figures, such as when he appears as a divine messenger to Saul (9:5, paralleled at 26:15, and expanded at 22:8–10; also 9:10–17, 27).

5 The command to Saul: necessity is placed on him

The vision and command to Saul (9:3–6) find a parallel in the subsequent vision and command of the Lord to Ananias, instructing him to meet with Saul (9:10–16). God is at work in these events; Luke reports that it is the divine voice (speaking through Jesus) which addresses both Saul (9:4–6) and Ananias, when he speaks of Saul (9:15–16).

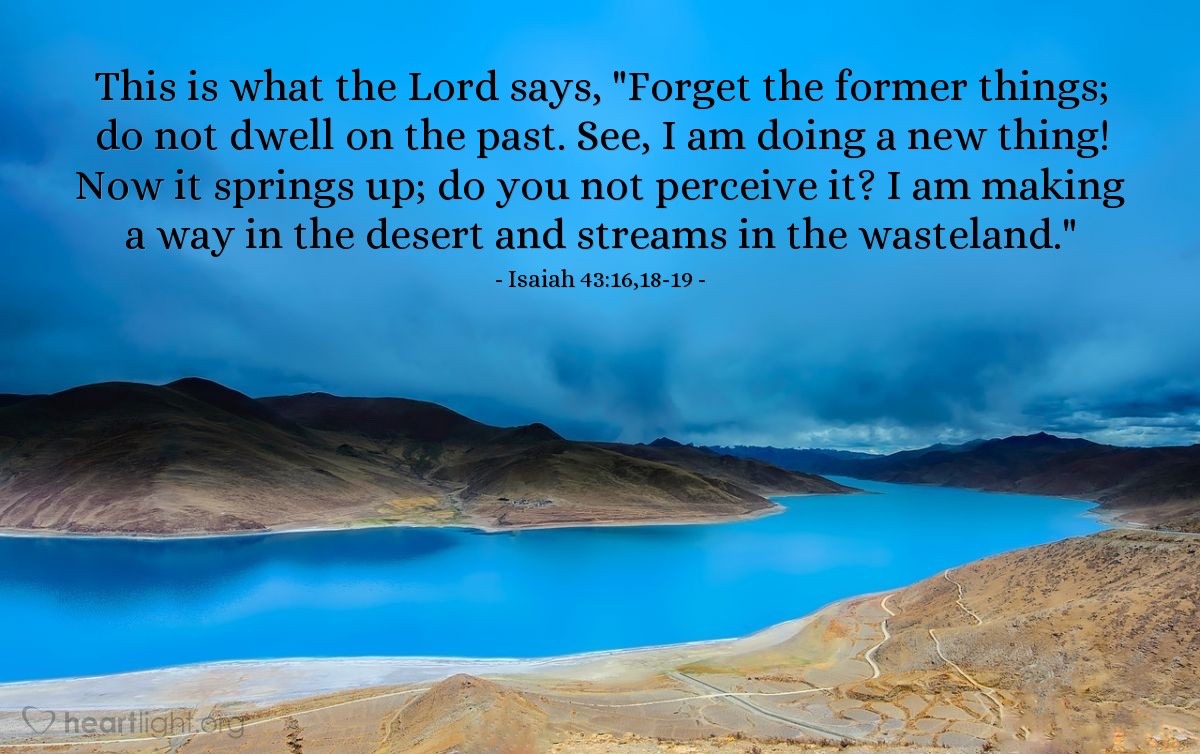

The theme of divine necessity has already been present in the Jerusalem narrative, both with reference to events narrated (1:22; 3:21; 4:12;19–20 5:29) and with reference to the death of Jesus (2:23; 4:28). This theme is stated in both divine speeches: to Saul, who is given a general charge: “it will be told to you what you must do” (9:6); and to Ananias, who is instructed to tell Saul “I will show him what he must suffer” (9:16), because “he is a chosen vessel for me” (9:15). Both statements establish that Saul must do what is prescribed, as a part of “the plan of God”.

6 The significance of Saul (Paul) in Luke’s story

Indeed, Saul is a critical agent in the execution of the necessary plan which God has for the believing communities in Jerusalem, Damascus, and beyond. Acts 13–28 is not solely about what was done by Paul (as he is then known); it is unambiguously about “what the Lord did through the activity of Paul” (14:27; 15:4,12; 21:19).

The other dimension of Saul’s role will become evident by implication throughout the latter half of Acts; that is, he stands as a model for what faithful proclamation and faithful discipleship entails. All that Paul does and says, and how he deals with what he encounters, functions as a role model for the readers of Luke’s narrative. Luke has Paul claim this explicitly in his final speech to the elders of Ephesus (20:35), soon before his arrest in Jerusalem. This is underscored by Paul’s two repetitions of the story of his conversion and call, with alterations and elaborations, in the final section of Acts.

7 Saul and Ananias

After being blinded, Saul is brought back to wholeness by Ananias, who acts in ways consistent with membership of “the Way”. Ananias lays his hands on Saul to heal him (9:17), a divinely-endowed ability (4:28) exercised by the apostles in Jerusalem (5:12) and Samaria (8:17). He tells him that “the Lord sent me” (9:17), a phrase which evokes the divine commissioning of Moses (7:34; cf. Exod 3:9-15, 4:13, 5:22–23), the sending of the angel Gabriel (Luke 1:19,26) and the task of Jesus (Luke 4:43; cf. 4:18).

Ananias then commands Saul to be “filled with the holy spirit” (9:17), repeating the divine action already evident in Jerusalem (2:4,38, 4:31) and Samaria (8:15–17). Like Peter (4:8) and Stephen (7:55), Saul is now filled with the spirit. Philip, too, is guided by the spirit (8:29,39), although the precise terminology of “being filled” is not applied to him.

The association of laying-on of hands with this spirit-filling is reminiscent of the account of how Joshua, “a man in whom is the spirit”, was commissioned as YHWH directed through Moses by the laying-on of hands (Num 27:18–23, esp. v.23). Like Joshua, Saul has been given authority over God’s people (Num 27:20) as “a chosen vessel” who will bear God’s name (9:15). Paul is then baptised (9:18), following the pattern set for new believers by Peter (2:38) and Philip (8:16). A new chapter in the story is unfolding.

*****

See also https://johntsquires.com/2022/04/26/people-of-the-way-acts-9-easter-3c/

*****

This blog is based on a section of my commentary on Acts in the Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, ed. Dunn and Rogerson (Eerdmans, 2003). I have also explored the theme of the plan of God at greater depth in my doctoral research, which was published in 1993 by Cambridge University Press as The plan of God in Luke-Acts (SNTSM 76).