I have suggested that reading the orderly account (which we know as Luke’s Gospel) requires attention to a number of elements, with one looking back to sources, to see how they are used in telling the story of Jesus, as the other eye looks forward to subsequent events, to see how they influence the story of Jesus. See https://johntsquires.com/2022/01/17/with-one-eye-looking-back-the-other-looking-forward-turning-to-lukes-gospel-i-year-c/

As we read, and reflect on, this account in this way, we may well note a number of key features that characterise this orderly account.

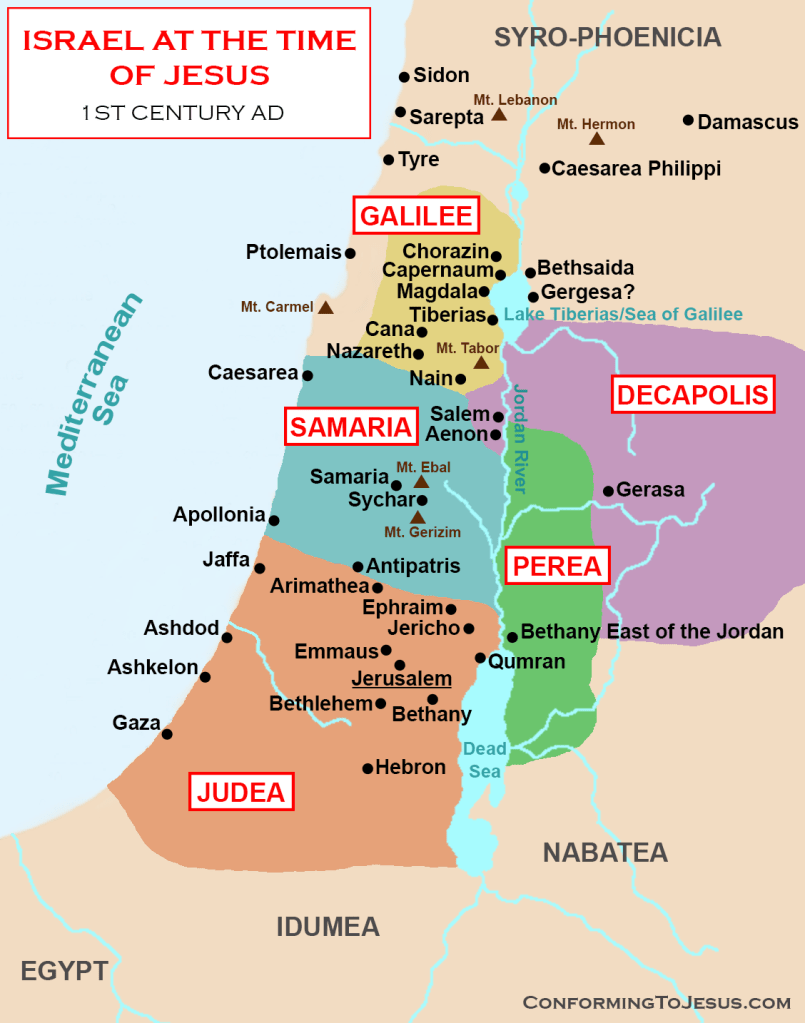

I have previously noted the strong commitment in this orderly account to the claim that the message of good news about the Jewish man, Jesus, and his Jewish followers, has implications that are universal. This is a story that makes its mark beyond Judea, through Samaria, far beyond—“to the ends of the earth”. See https://johntsquires.com/2022/01/18/a-light-for-the-gentiles-salvation-to-the-ends-of-the-earth-turning-to-lukes-gospel-ii-year-c/

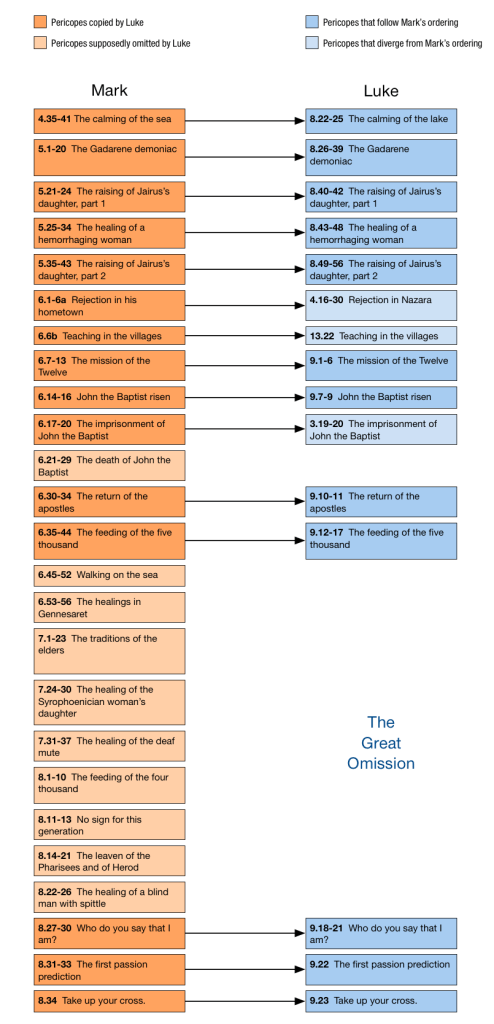

As we look steadfastly back to the earlier source that was used in the writing of this orderly account—the beginnings of the good news, which we call the Gospel according to Mark—we do well to note the omissions in the narrative that Luke shapes. These omissions are significant.

Most strikingly, there is a large section of Mark’s narrative (6:45–8:26) missing in Luke’s orderly account. We would have expected it at Luke 9:17, immediately after the feeding of the five thousand (Mark 6:30–44; Luke 9:10–17); but Luke 9:18 jumps to to Peter’s declaration that Jesus is Messiah (Mark 8:27–30). This is sometimes known as The Great Omission (a term coined as a riff off The Great Commission in Matt 28:16–20). Why has Luke omitted it?

Luke’s commitment to the universal impact of the message of Jesus can explain this. The omitted section includes the story of Jesus’ encounter with the Syro-Phoenician woman (Mark 7:24–30), which Matthew includes (Matt 15:21–28) because it reinforces his view that Jesus avoided Gentiles and Samaritans. Luke would have been happy to omit this, especially as it infers that Gentiles are dogs (Mark 7:27–28: Matt 15:26–27).

Immediately prior to this story in Mark (and Matthew) is the debate about Torah halakah that Jesus has with scribes and Pharisees, after they noticed that “some of his disciples were eating with defiled hands, that is, without washing them” (Mark 7:1–23; Matt 15:1–20).

The editorial declaration that Jesus “declared all foods clean” (Mark 7:19) is withheld by Luke from his story of Jesus, and deployed as a key statement in what serves as a major pivotal moment in the life of the early church—the moment when Peter sees a vision in which a voice from heaven declares, “What God has made clean, you must not call profane” (Acts 10:15; 11:9).

This central affirmation about food is then applied to relationships with people: “God has shown me that I should not call anyone profane or unclean” (10:28). So the Jew Peter and the Gentile Cornelius eat together at table—and provide a striking image for the life of the community of faith in Luke’s own time. Luke has removed the declaration of Jesus in the Jewish halakhic debate about food, so that it can serve as the punchline in the pivotal moment in volume 2—the turn to the Gentiles.

This orientation towards Gentiles is evident at many points in the story told in Acts. That is not to say, however, that the Jewish origins of the movement are ignored or left behind. Indeed, it is noteworthy that the believers in Jerusalem remain connected to the Temple, participating in the worship of that place (Acts 2:46; 3:1) and used the Temple area as the basis for their public preaching (5:17–21, 25–26; 5:42).

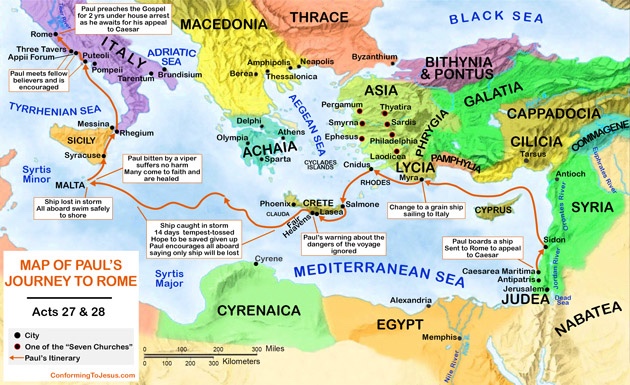

In like fashion, Paul and his fellow workers are regularly found proclaiming the good news in synagogues—in Antioch (13:14–15, 43, 44), Iconium (14:1), Thessalonians (17:1–3), Beroea (17:10–11), Athens (17:16–17), Corinth (18:4) and Ephesus (18:19 and again in 19:8–10). The “place of prayer” by the river in Philippi (16:13) was, most likely, also a place of gathering for Jews. Finally, Paul visited the Jerusalem Temple and took part in a purification ceremony there (21:17–36, when he is arrested).

However, in some of the locations, Paul addresses Gentiles who had already expressed interest in Judaism, known as godfearers (13:16, 26; 13:43, 50; 17:4; 17:17). Indeed, after commotions broke out in synagogues relating to the message that Paul was preaching, he turned explicitly to Gentiles—in Antioch (13:48) and Iconium (14:1–3), in Corinth (18:7) and in Ephesus (19:9–10), as well as in two highly significant scenes in the public marketplaces of Athens (17:16–34) and Ephesus (19:23–41).

Commentators regularly highlight the three occasions in Acts when Paul explicitly declares that, because of Jewish intransigence, he is turning to the Gentiles.

He first declares this when Jews in the Antioch synagogue rebuff him: “since you reject it and judge yourselves to be unworthy of eternal life, we are now turning to the Gentiles. For so the Lord has commanded us, saying, ‘I have set you to be a light for the Gentiles, so that you may bring salvation to the ends of the earth’” (13:46–47, citing Isa 49:6).

Paul says this again in Corinth, after similar upheavals: “when they opposed and reviled him, in protest he shook the dust from his clothes and said to them, “Your blood be on your own heads! I am innocent. From now on I will go to the Gentiles” (18:6–7). In the final scene of the book, while Paul is under house arrest in Rome, he makes it very clear that “this salvation of God has been sent to the Gentiles; they will listen” (28:28).

In the first two instances, whilst Paul moves out of the synagogue to continue preaching to Gentiles, in each case he immediately returns to the synagogues where he speaks to Jews (14:1 and 18:19, already noted above). Thus it makes sense for the final declaration in Rome to be interpreted in the same way. Paul expresses frustration at the rejections he experiences from Jews and sees fertile territory amongst Gentiles; but he is not saying that the Gospel no longer is relevant to Jews.

I think it is important not to over-interpret these three declarations as definitive rejections of the Jews within the providential plan of God. Rather, it is Paul’s way of emphasising the universal orientation and global relevance of the Gospel—a message which, as we have seen, is integral to Luke’s theology throughout both volumes of his orderly account.

The three declarations of a “turn to the Gentiles” provide narrative fulfilment of the early prophetic announcement of Simeon, that Jesus brings God’s salvation, “prepared in the presence of all peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles and for glory to your people Israel” (Luke 2:30–32). That is the primary focus of the two-volume work that Luke writes.