This coming Sunday is the second Sunday after Pentecost. This is the longest season in the church’s year, stretching all the way from Pentecost Sunday (two weeks ago in early June) to the Reign of Christ (on the 24th Sunday after Pentecost, at the end of November). Each Sunday during this season, the lectionary offers a set of readings from the prophets in Hebrew Scriptures, some letters of the New Testament, and the orderly account of the things fulfilled amongst us, which we know as the Gospel according to Luke.

On the prophets, see https://johntsquires.com/2022/06/13/the-voice-of-the-lord-in-the-words-of-the-prophets-the-season-of-pentecost-in-year-c/

We have already launched into reading and hearing from Luke’s orderly account in the Sundays of Epiphany, earlier in the year, and in some of the Sundays in the seasons of Lent and Easter. From this Sunday, we hear passages from chapter 8 onwards, culminating in the final speech of Jesus to his followers in chapter 21.

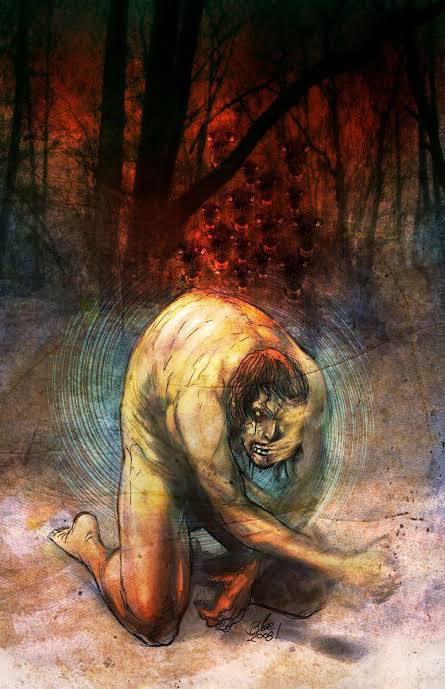

The story for this Sunday tells of the encounter between Jesus as a man possessed by demons. At the moment of encounter, the man cries out a question which stands at the head of all we will read over the coming six months: what have you to do with me, Jesus, son of the Most High God? (Luke 8:28). That is a good question to pose as we read and hear each of the selections from the orderly account that we will encounter in coming weeks.

As Jesus sets his face towards Jerusalem (9:51–56), what does he have to do with us? As Jesus teaches in the house of Mary and Martha (10:38–42), what does this have to do with us? As he teaches about prayer (11:1-13), tells parables about the right use of wealth (12:13–21; 16:1–13; 16:19–31), the generous hospitality of an open table (14:1–14), the gracious welcoming-back of the one who was lost (15:11-32), we should ask: what do you have to do with us, Jesus?

As Jesus receives the gratitude of a returning healed Samaritan (17:11–19), tells of the persistence of a widow (18:1-8), or enters the house of a reformed chief tax collector (19:1–10), we should ponder: what do you have to do with us, Jesus? When he enters the temple, debates with others (20:27–38), and speaks of the time still to come (21:5–19), we ask once more: what do you have to do with us, Jesus?

*****

The Other Side

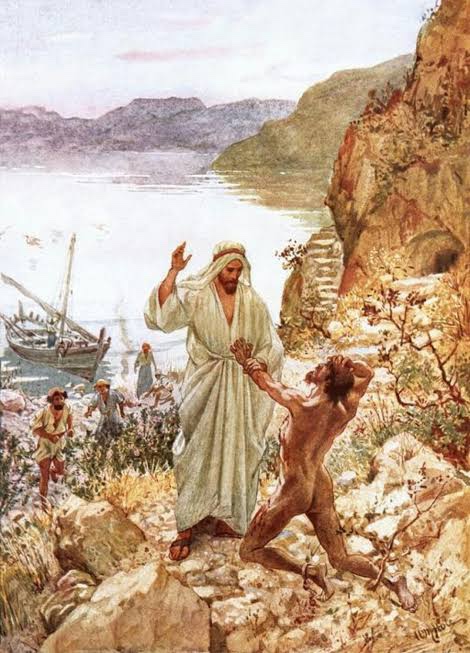

Jesus encounters this demon-possessed man “on the other side” (Luke 8:22). He has crossed the lake and arrived at “the country of the Gerasenes, which is opposite Galilee” (8:26). His activity to this point has been amongst his own people, in Galilee (4:14, 31; 5:17), in Nazareth (4:16), Capernaum (4:31; 7:1), in synagogues in various towns (4:15, 33; 6:6; inferred in 8:1; and the textual variant of 4:44, Galilee, is surely to be preferred).

People in Galilee approached him to be healed or exorcised (4:40–41); others from Judea and Jerusalem had come to Galilee to hear him and be healed (6:17). Even some from “the coast of Tyre and Sidon”, to the northwest, beyond the land of Israel, had come (6:17). And in the story of the healing of the centurion’s son (7:1–10), Jesus has some contact—albeit at a distance, mediated through Jewish elders—with the Gentile centurion. To Jews and Gentiles alike, Jesus was much in demand!

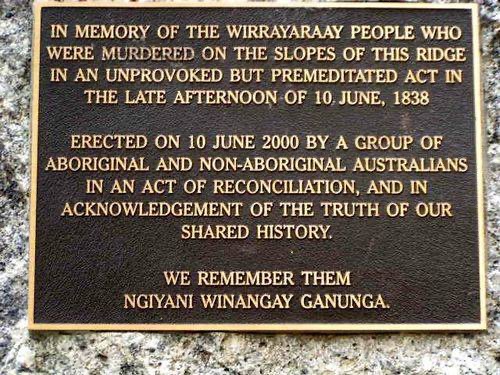

By crossing the lake (8:22–25), Jesus steps onto Gentile territory—the Decapolis—and engages directly with non-Jews; not only this man (8:27), but “people [who] came out to see what had happened” (8:35), “all the people of the surrounding country of the Gerasenes” (8:37). When these people, “seized with great fear”, asked Jesus to leave, he obliged; “he got into the boat and returned” (8:37), back to the Jewish side of the lake.

Nevertheless, the word about Jesus was “out” amongst the Gentiles; indeed, as Jesus had commanded the exorcised man to return home and “declare how much God has done for you” (8:38), so the man was “proclaiming throughout the city how much Jesus had done for him” (8:39).

The phrase prefigures Luke’s later declaration about “all that Jesus did and taught” (Acts 1:1, summarising the whole of the Gospel story), and the apostolic proclamations of “all that God had done with them” (Paul and Barnabas in Antioch, Acts 14:27; in Jerusalem, 15:4, 12) and “the things that God had done among the Gentiles through his ministry” (Paul in Jerusalem, 21:19). It also echoes the earlier affirmation of Elizabeth, “what the Lord has done for me when he looked favorably on me” (Luke 1:25) and the song of Mary, “the Mighty One has done great things for me” (1:49).

The man is thus the first active evangelist operating independently in Luke’s orderly account—proclaiming the good news even before the twelve are sent out “to proclaim the kingdom of God and to heal” (9:1–6), even before the seventy-two are similarly despatched, two-by-two, to declare “the kingdom of God has come near to you” (10:1–12).

*****

Signs of uncleanness

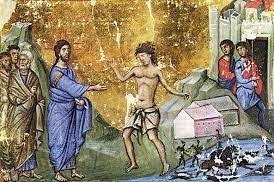

In exorcising the demons from the man in “the country of the Gerasenes”, Jesus encounters a man who is outside the boundaries of the people of God. There are a number of markers which indicate how “unclean” or “impure” this man would have been regarded by faithful Jews like Jesus and his followers. The location was outside the holy land of Israel (8:26); this is the first marker.

In a later rabbinic document, the Mishnah, a complex map of holiness was set forth, beginning with the statement that “there are ten grades of holiness: the land of Israel is holier than all other lands” (m.Kelim 1.6). (This discussion moves through the series of holiness grades, culminating with the statement that “the Holy of Holies is holier, for only the high priest, on Yom Kippur, at the time of the service, may enter it”; m.Kelim 1.9.) Assuming that this later understanding also applied earlier, at the time of Jesus, then his venturing across the lake was moving into unholy territory.

(Jerome Neyrey provides an extensive discussion of “clean/unclean, pure/polluted, holy/profane”, in his article on “the idea and system of purity”, at https://www3.nd.edu/~jneyrey1/purity.html

The man whom Jesus encountered was naked (8:27), another marker of his state of uncleanness. Being naked is linked with an unsatisfactory state of being in one of the stories found at the beginning of the scrolls of the Torah. The man (Adam, son of the earth) and the woman (Eve, source of life) experience this revelation after eating “the fruit of the tree that is in the middle of the garden” (Gen 3:1–6), “the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves” (Gen 3:7).

In stories following in later scrolls, nakedness may be portrayed negatively and linked with shame (Noah at Gen 9:22–23; the mother of Jonathan, 1 Sam 20:30), sinfulness (Jerusalem at Lam 1:8; Isa 47:3), poverty (Deut 28:48; Isa 58:7), violence (Hab 2:12–17), or sexual immorality (Ezek 16:36–38; 23:27–31; Hos 2:2–10; Nah 3:4–5). And in Roman society (the dominant culture within which the Gospel of Luke was written), nudity could be used as a powerful social constraint; a master could make a slave naked “for the explicit purpose of shaming them and reinforcing the power they maintain over them”. See http://www.humanitiesresource.com/classical/articles/roman_sexuality.htm

The man who approached Jesus “did not live in a house but in the tombs” (8:27). Dead bodies were a prime source of conveying uncleanness (Lev 21:1–3); so “those who touch the dead body of any human being shall be unclean seven days” (Num 19:11; see also Haggai 2:13). Living amidst the tombs where dead bodies were laid ensured that, under the prescriptions of the Torah, the man was perpetually unclean (Num 19:16), and thus should be avoided.

The man was “kept under guard and bound with chains and shackles which he would tear apart and break free (8:29). This description suggests a supernatural strength, but perhaps also signifies a refusal to be bound by the expectations of custom, with such reckless, violent behaviour. Certainly the demons which possessed the man have guided him to behave in ways that would be considered “anti-social”; so, he was not quite unclean in the ritual sense, but his actions placed him outside the expected patterns of society.

The anti-social behaviour of the man is intensified in Mark’s longer account; “night and day among the tombs and on the mountains he was always howling and bruising himself with stones” (Mark 5:5). This detail is omitted in Luke’s version. However, Luke does report that the man was “driven by the demon [singular] into the wilderness” (Luke 8:29. The wilderness, of course, was the place for testing—of Israel (Exod 15:25–26; Deut 8:16; Ps 95:8–9); of Jesus (Luke 4:1–13), of Paul (2 Cor 11:26).

Indeed, it was not just one demon that had possessed the man; “many demons had entered him” (8:30), which explains his incredible strength and his actions outside the expected social norms. The man himself labelled these demons Legion—a clear allusion to the Roman army cohort of a legion, which at this time would have been 5,600 men, armed and ready to fight. The level of uncleanness in this man, therefore, possessed by so many demons, was immense. (The name of the demon is likewise Legion at Mark 5:9; Matthew omits this identification.)

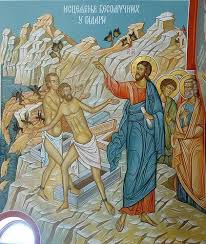

Finally, the symbolism of sending the demons into “a large herd of swine [which] was feeding” on the nearby hillside (8:32) is potent. Pigs, of course, were anathema to Jews; “the pig, because it divides the hoof but does not chew the cud, is unclean for you” (Deut 14:8; likewise, Lev 11:7). From one person with numerous markers of uncleanness, the demons are sent into a group of animals that are clearly and definitively unclean. The making-unclean effect of Legion is transferred into the hapless already-unclean swine, who then plunge into the sea.

The sea, of course, for the people of Israel, is another marker of the territory beyond—a place of threat and danger. Israelites were not seafaring people; their natural habitat was wilderness and rocky hills. The sea was a dangerous place (Ps 30:1; 69:1–3). Only God could control the sea and the evil it symbolized (Ps 65:5–7; 77:19; 89:9; 93:3–4; Exod 14:15–16; Isa 51:10). The sea was the home for Leviathan, the great sea monster (Isa 17:12; 27:1; 51:9–10).

The prophet Daniel relates his vision of “the four winds of heaven stirring up the great sea, and four great beasts came up out of the sea” (Dan 7:2–3)—those four beasts, it is understood, represent the political and military threats to Israel from the four great empires. So, sending the unclean swine, now possessed by the Legion of demons, into dangerous sea, represents a complete cleansing and restoration of the man.

Luke alone intensifies this moment in the story, as the demons begged Jesus “not to order them to go back into the abyss” (8:31). The abyss is identified in deutero-canonical literature with “Hades in the lowest regions of the earth” (Tobit 13:2), the opposite extreme from the heavens (Sirach 1:3; 16:18; 24:5). In Revelation, the word is translated “bottomless pit”, the source of a plague of locusts (Rev 9:1–11) and the home of the Beast (Rev 11:7; 17:8) and the place where “the dragon, that ancient serpent who is the Devil and Satan” is thrown at the end (Rev 20:1–3).

Do the pigs actually plunge all the way down into abyss? This is left to the imagination of the hearer or reader of the story.

*****

Luke has received the story of the encounter between this man and Jesus in the earlier account of Jesus that we attribute to Mark (Mark 5:1–20). As Luke uses this narrative as a key source for his orderly account, he has here maintained the structure and most of the details of Mark’s narrative. Matthew also has this story (Matt 8:28–34), but he has significantly reduced the narrative—and there’d are two men, not one, who emerge from the tombs (Matt 8:28).

Mark has Jesus return to Jewish territory after this encounter (5:21), but then make a second foray across the lake to the other side (6:45; he returns to Jewish land again at 8:13). During that second trip, there are significant events relating to the way that Jesus stretches the boundaries of the people of God.

Luke omits all of that second journey, and the key events included in Mark’s account of that second trip: the discussion about “the tradition of the elders” (Mark 7:1–23), the encounters between Jesus, the Syrophoenician woman, and the deaf man (7:24–37), and feeding the 4,000 (8:1–10). Instead, Luke concentrates the visit of Jesus to Gentile territory entirely within this single narrative, telling of the casting out of demons from the unclean man in “the country of the Gerasenes, opposite Galilee” (Luke 8:26).

This single story contains all that we need to know about the attitude of Jesus towards “unclean” Gentiles. In one encounter, the massed forces of demonic opposition are engaged, subdued, and dispatched—the shackled man is unchained, the legion of unclean demons is sent into unclean swine, the swine dive into the chaos of the menacing, swirling sea, and the man is restored to right relationships.

Indeed, this man is the first to receive a commission from Jesus to “declare how much God has done for you”. His testimony to his encounter with Jesus begins a community of disciples “on the other side”. The good news is spreading far already, at this early stage of the public activity of Jesus!