Every Christmas, we are surrounded by images of the much-loved nativity scene: the infant Jesus, in a cradle, with his mother Mary sitting and his father Joseph standing nearby, surrounded by animals (cows, most often), with a group of shepherds (perhaps with their sheep) to one side, whilst on the other side three colourfully-dressed men stand with presents in hand: gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

We see this image everywhere. But it is not an accurate portrayal of what was happening at the time when Jesus was born. For one thing, it is not a photograph of an actual event. Far from it. It is not even based on a written report from the first century, telling that this was what happened.

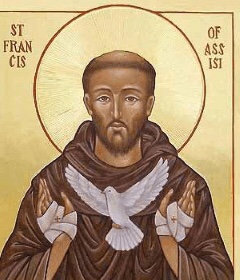

The traditional scene that we see today did not come into being until it was invented by the medieval friar, Francis of Assisi. Before that, it did not exist. And no Gospel account actually tells of cows mooing beside the newborn child, or of the newborn infant making no crying sounds, or of the sheep baaing alongside the cows, that we see in the traditional nativity scene.

Francis is the most popular Catholic saint in the world. He is the one who preached to the birds; blessed fish that had been caught, releasing them back into the water; and communicated with wolves, brokering an agreement between one famous ferocious wolf and the citizens of a town that were terrified of it. There is no surprise, then, that Francis used real animals when he created the very first, live, Christmas nativity scene. As a result of all these stories, Francis is the patron saint of animals and the environment. And he is the inventor of the familiar nativity scene.

Actually, this scene is a compilation of two quite discrete stories, told decades later, offering very different perspectives on the event, providing two somewhat different emphases in the story of the birth of this child. The nativity scene merges and blends the story found in the orderly account constructed by Luke, and the book of origins compiled by Matthew. Wise men and shepherds sit on each side of the family group, at the same time, in the same place, in this traditional scene. But not in our biblical accounts.

In the opening chapters of Matthew, we encounter the pregnant Mary, the newborn infant Jesus, his father Joseph, a bright star in the sky, visitors from the east, the tyrannical rule of Herod, and slaughtered infant boys. In this story, Matthew is working hard to place Jesus alongside the great prophet of Israel, Moses. The early years of Jesus unfold in striking parallel to the early years of Moses. The parallel patterns are striking.

Luke tells a more irenic version of the story than what is found in Matthew’s Gospel. The story told by Luke (usually represented through idyllic pastoral scenes and sweetly-singing angels), actually tells of a widespread movement of the population that meant a pregnant Mary, accompanied by Joseph, had to travel afar and find lodging in a crowded town just as the most inconvenient time.

There are historical problems with this story: identifying the census as an actual historical event, and locating it accurately in time, both present challenges; the fact that Herod, ruling in Matthew’s account, died in 4BCE, but Quirinius, who ordered the census noted in Luke’s account, began as Governor in 6 CE. However, the combined story has entered the popular mindset as a real event and provides a clear and compelling picture of the holy family as refugees, because of decisions made by political authorities, whether Herod or Quirinius.

We overlook, perhaps, that the shepherds who came in from the fields to pay homage to the newborn child would have been despised for carrying out a lowly and unworthy occupation. They were outcasts, considered impure and unclean, placed outside the circle of holiness within which good Jews were expected to live. In the Mishnah, a third century work which collects and discusses traditional Jewish laws, shepherds are classified amongst those who practice “the craft of robbers”. These are not highly valued guests!

Even though this is not an historical story, it is important for theological reasons. It is part of the foundational myth of the Christian faith. The writer of Matthew’s Gospel wants to make strong correlations between Jesus and Moses, not only in the mythological account found in the opening chapters, but also throughout the following chapters of the Gospel. The writer of Luke’s Gospel hints at his key themes in the opening chapter, and the develops a strong political and economic message throughout his Gospel: God reached out to the poor and powerless, and harshly judges the wealthy and powerful.

As myth, the tradition points to important truths. Matthew’s account of “the Slaughter of the Innocents”, for instance, although generated by his Moses typology, still grounds the story of Jesus in the historical, political, and cultural life of the day, when tyrants exercised immense power. Even though we recognise Matthew is not reporting an actual historical event, his narrative provides a dreadful realism to a story which, all too often in the developing Christian Tradition, became etherealised, spiritualised, and romanticised.

By the same token, Luke’s recounting of the visit of the outcast shepherds to the infant child and his family indicates that those on the edge were welcomed by Jesus throughout his ministry. He grounds the message of the Gospel in the heart of the needs of the people of his day.

So even as we recognise that the Christmas story is not history, we can appreciate the insights that it offers us as a mythological narrative. It is worth celebrating: not as an actual historical event, in the way it is traditionally portrayed, but as the foundation of the faith that we hold: in Jesus, God has come to be with us.

See also

You can read a more detailed discussion of my views on this story at https://johntsquires.com/2018/12/19/what-can-we-know-about-the-birth-of-jesus/

I’m not a scholar, I am a follower of Christ our savior and have a lot of questions about todays teaching and Gods word.

Myth, Mythical, Mythology, all means not true or made up.

So we were taught in School about Greek Mythology, Greek Gods and Goddesses. Now from what I can make out these Mythical Gods and Goddesses was in the time Jesus was on earth and that his teachings were known.

So my question is, why were we not taught about those parts of the stories.

These Greek “God and Goddess” were real they existed, they were not Gods and Goddess, but believed they were and it was taught at that particular time that they were to be worshiped.

Also pagan festivals and worship of these false Gods were part of this time, and I continue to read and track back our “Christian” Holidays to coincide with the pagan holidays.

I wonder as a Christian how that could be, how could we really be taught that in Gods words these dates that originated as pagan holidays are now to be celebrated in Jesus name.

I am of Baptist Religion so, I am truly struggling with conviction from God for the truth, deception is everywhere and can carry on for many years so it’s not a far stretch for me to believe that there are things in our culture today that certainly have be desguised to pull Christian away from the purpose of God and his word.

Good article, reflecting recent archeology findings. It gives more credence to the essence of the nativity story (less the animals…)

https://biblearchaeologyreport.com/2023/12/21/top-ten-discoveries-related-to-christmas/?fbclid=IwAR3N0AG_zo2vwcKoL7eCdOsV67N8u8Fzq3fjPP26bmHk8vq2bBYz2vTZwBo

Thanks Tarso. This article demonstrates that we have evidence for the existence of Jewish habitation in first century Nazareth and Bethlehem, of Nabataean wise men, of fragments of early copies of the Gospels, of the kataluma in ancient Jewish homes, of the arrogance of Augustus, and of patristic and medieval claims about locations made centuries after the events purported to have occurred. We knew all of this long ago. There is nothing that specifically and definitively “proves” any element of the biblical narratives about the birth of Jesus; only that they were written in ways that made them feel historically plausible. Sorry.

No need to be sorry. The essence of Christianity is not in the details of the Nativity, but in the original creed, developed in the very first years after the facts took place and repeated in the incipient community of believers: that Christ died on the Cross, was buried, and was raised from the dead on the third day. And this creed was then incorporated in the first letters of St Paul, a few years later. That is the crux of the matter.

Hmmm … I think it was the other way around: first the oral tradition, then the letters of Paul followed decades later by the Gospels, and in the developing church the creed then came to be formalised, being adopted at Nicea in 325CE.

Yes, I agree, first came the oral tradition, which also provides insights into the Nativity stories we talked earlier. What I meant is that some letters of Paul, written already in the ´40s, already include what he received from the first christians, which was circulating probably from right after the ressurection. It is true that the formal Creed would be formalised only centuries later, but the essence of the creed had already been in circulation also for centuries. Is short: if there may be some inconsistencies in the Nativity story, as you point out, the fundamental tenets of the faith are corroborated since the very beginning.

In a more literary vein (George MacDonald: An Anthology by CS Lewis): “But herein is the Bible itself greatly wronged. It nowhere lays claim to be regarded as the Word, the Way, the Truth. The Bible leads us to Jesus, the inexhaustible, the ever unfolding Revelation of God. It is Christ “in whom are hid all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge”, not the Bible, save as leading to Him”

I doubt that many of Paul’s letters that we have were written in the 40s. 1 Cor, which contains the proto-credal claims in ch.15, is from the 50s, after Paul’s visit when Gallio was proconsul (50–51 CE). Fragments elsewhere in the NT and patristic writers do show early attempts to express beliefs in succinct, memorisable phrases, but there is no full credal statement until Nicea in 325 CE—At the urging of Emperor Constantine.

Faith is not proof. Belief is what people can commit to, because it makes sense of the reality that we experience, not what can demonstrably be proven, in a quasi-scientific manner. It’s an important distinction.

So the Bible is testimony—bearing witness to human experience of the transcendent and how it becomes immanent in earthly life. It in no way provides “proof” or declares “dogma”. It invites us to reflect on how we know God, and where the signs of God’s presence and activity can be glimpsed in our world today.