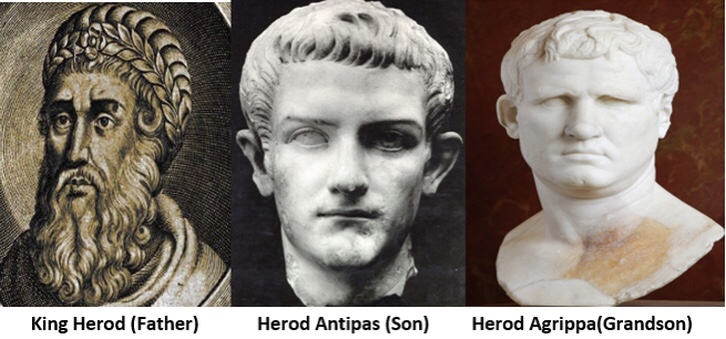

Every year, the “Christmas story” gets swamped by Luke’s story in his orderly account, of the angels, the shepherds, “no room at the inn” and “good news of great joy”. From Matthew’s account in his book of origins, the visit of the sojourning magi from the east, offering their splendid gifts to the newborn, gets a place in the story—but not the tragedy of the terrible massacre perpetrated by the vengeful ruler, Herod.

Every Christmas, the majestic, soaring words from the poetic prologue to John’s book of signs is read in worship, and sometimes preached on; “in the beginning was the Word … and the Word became flesh, and pitched his tent in amongst us”. What never gets a look in, at any point in the Advent or Christmas seasons, is how the other Gospel, that attributed to Mark, portrays the beginnings of Jesus.

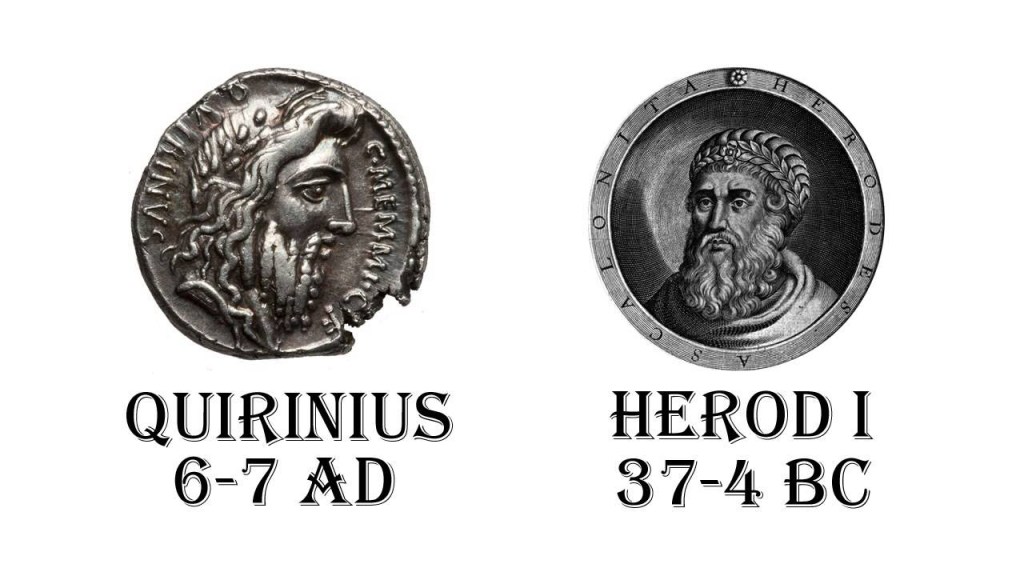

“In those days Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan” (Mark 1:9) is how Jesus is introduced. This is the adult Jesus, not the newborn infant. There is no mention of Bethlehem, nor the rampage of Herod; no reference to magi travelling from the east, bearing gifts, nor to a census ordered under Quirinius, necessitating short-term accommodation. There is no story of the infant Jesus at all—and most strikingly, no mention of Mary and Joseph.

Rather, in Mark’s narrative which reports the beginning of the good news about Jesus, the chosen one, Jesus distances himself from his family. “Who are my mother and my brothers?”, he asks, when confronted by scribes from Jerusalem and labelled as “out of his mind” by his own family (Mark 3:21, 33). People of his hometown (Nazareth) identify him, not as “son of Joseph”—only in John’s book of signs do his fellow-Jews identify him as “son of Joseph” (John 6:42). And it is up to Luke and Matthew, each in their own way, to link Jesus, as a newborn, to these parents.

In Mark’s account of the scene when the adult Jesus returns to his hometown, he is “the carpenter, the son of Mary” (6:3). This is the only time that the name of his mother appears in this earliest account of Jesus; and there is simply no mention, by name, or by relationship, of his putative father. (Some scribes later modified this verse (Mark 6:3) to refer to him as “son of the carpenter and of Mary”, to align Mark’s account with how Matthew later reports it at Matt 13:55.)

Other than this one reference, Mark makes no reference to Jesus’s parents. He is simply, and consistently identified as “the son of God” (Mark 1:1; 3:11; 5:7; 9:7; 15:39). On one occasion, he is addressed as “son of David” (10:47–48; although this description is the subject of debate at 12:35–37). More often, in this earliest of Gospels, using a term taken from Hebrew Scripture, Jesus refers to himself, or others refer to him, as “the son of humanity” (2:10, 28; 8:31, 38; 9:9, 12, 31; 10:33, 45; 13:26; 14:21, 41, 62; see Ezek 2:1, 8; 3:1, 4, 16; etc; and Dan 7:13). The origins and identity of Jesus, in Mark’s eyes, relate more to the larger picture—of his Jewish heritage, in his relationship to the divine, and with his role for all humanity—than to the immediacy of parental identification.

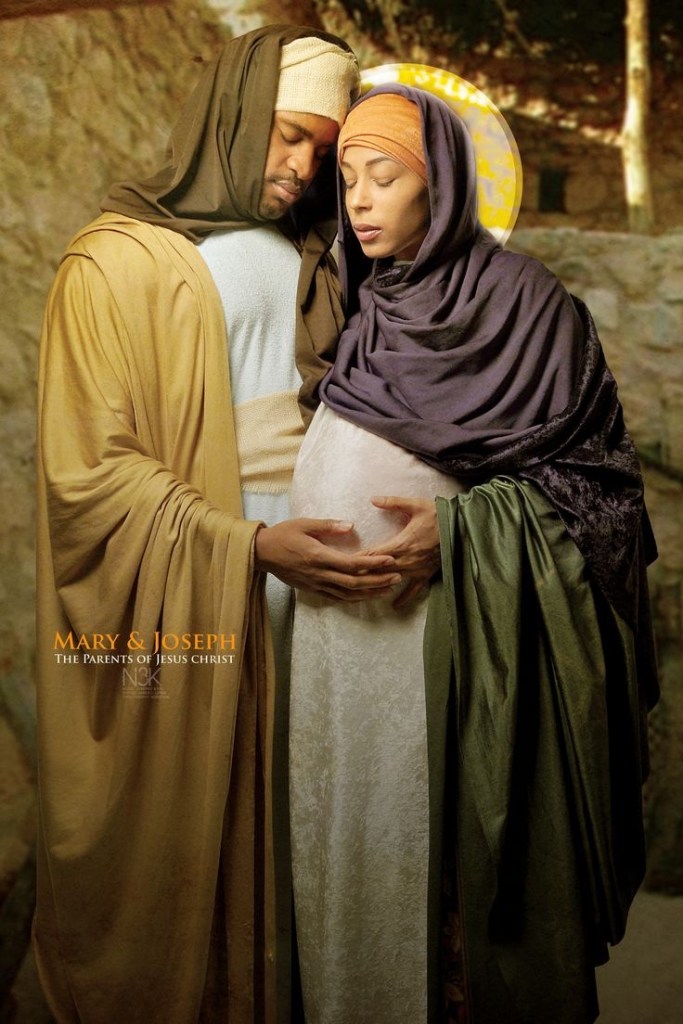

Mark knows nothing of what transpires in Luke’s orderly account, as “Joseph went from the town of Nazareth in Galilee to Judea, to the city of David called Bethlehem, because he was descended from the house and family of David; he went to be registered with Mary, to whom he was engaged and who was expecting a child” (Luke 2:4–5).

He certainly knows nothing of the way that Luke has spliced the story of Jesus into the story of John the baptiser (related through their mothers, Luke 1:36) such that John is filled with “the spirit and power of Elijah” (Luke 1:17) to function as “the prophet of the Most High [who will] go before the Lord to prepare his ways” (Luke 1:76), whilst Jesus “will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High, and the Lord God will give to him the throne of his ancestor David” (Luke 1:32), and then himself will be “filled with wisdom” (Luke 2:49) and, indeed, “filled with the Holy Spirit” (Luke 4:1, 14).

Mark also knows nothing of what is narrated in the Matthean book of origins, of the time when, after a visit from magi from the east, “Joseph got up, took the child and his mother by night, and went to Egypt”, and then “Joseph got up, took the child and his mother, and went to the land of Israel” (Matt 2:14, 21).

This author’s concern is both to locate Jesus firmly and schematically in his genealogy as “the chosen one, the son of David, the son of Abraham” (Matt 1:1–17), and to make as many parallels as possible with the story of Moses, the one whose life was imperilled by a powerful ruler (Exod 2:15; cf. Matt 2:13–14), who escaped the murderous rampage that occurred (Exod 1:22; cf. Matt 2:16), who fled into a foreign land (Exod 2:15; cf. Matt 2:14), and who then returned to where he had been born (Exod 4:20; cf. Matt 2:21). The regular reminder that “this took place to fulfil what the Lord has said through the prophets” (Matt 1:22; 2:4, 15, 17, 23) underlines this Mosaic typology.

In this regard, Mark is very much like Paul, the famous apostle who, some decades earlier, was able to refer to Jesus as “born of a woman, born under the law” (Gal 4:4)—that is, his Jewishness was important, but the name of that woman was not. And Paul refers to God’s Son as being “descended from David according to the flesh” (Rom 1:3)—that is, his Davidic ancestry was important, but even the name of his father, a descendant of David, was not. Mark and Paul both place their focus elsewhere, away from the baby, the manger, the magi, the star. The earlier witnesses to Jesus show no concern at all in this later accretions to the story, with which Luke and Matthew each introduce Jesus.

What would Mark (or Paul) think of the way we have appropriated these two later narratives, offered by their creators as myths, stories to convey deep truths through striking storylines which have been creatively constructed? What would he think of the ways that we have read them as historical reports, literally chronicling actual happenings? What would he think of the thoroughly unhistorical blurring together of the two stories, with shepherds and magi coming together at the crib at the same time?

Perhaps next year, when the lectionary focusses on the Gospel of Mark, we might let this Gospel govern the way that we approach the season of Christmas? Perhaps the focus might be, not on angels and magi, not on shepherds and tyrants, not on the trimmings and trappings of the commercialised season, not even on the incarnate presence of the eternal Word, but on the significance in daily, human, life, of this person, Jesus? Now that would be truly counter-cultural, truly alternative, truly faith-focussed amidst the razzamatazz of the times!