Recent scholarship has recognised the Jewish character of the first Gospel in the New Testament—the work that I refer to as the book of origins (for that is my translation of how the book begins, in Matt 1:1).

A consensus is emerging that the book of origins was most likely written for a community that was still thoroughly immersed within its Jewish tradition. One place we can see that is in what is perhaps the most famous section of the Gospel, the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5–7). These chapters stand as an excellent example of how Jesus was understood, by Matthew, to be THE authoritative Jewish teacher, interpreting and applying the Torah, the Law of Moses, to all of daily life.

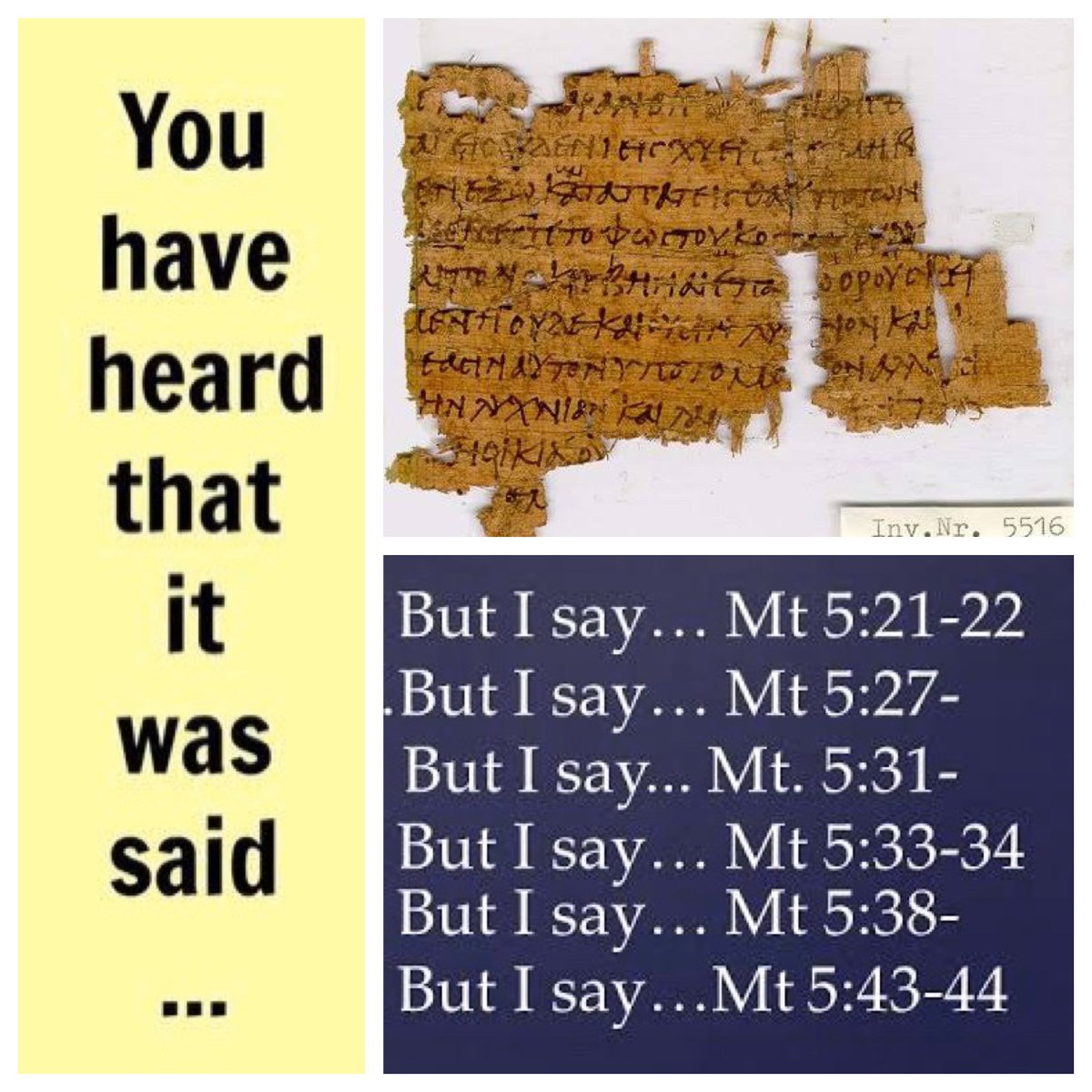

In this sermon, Jesus debates with the Pharisees concerning their interpretation of scripture. His pugnacious words, “you have heard it said … but I say to you …” (occurring six times within 5:21-48) reflect the common dialectical interaction that Pharisees (and, later, Rabbis) used to tease out the meaning of each commandment found within the Law. Torah teaching was inherently dialogical in nature; those teaching the Law would argue, back and forth, over what it meant and how it was to be followed.

As Jesus uses these established Jewish debating techniques, he proposes a way of living that is thoroughly grounded in Jewish ethics and practices, such as prayer, fasting, and almsgiving. The emphasis on righteousness is central to the discourse; four times during this sermon (5:6, 10, 20; 6:33) Jesus particularly emphasises the importance of being righteous.

Indeed, in the verse which culminates the Gospel passage set for this coming Sunday, Jesus is attributed as having taught his disciples that he is looking for an excess of righteousness: “unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (5:20).

That verse has followed straight after Jesus’ emphatic insistence that the Law, the whole of the Law, must still stand for his followers. “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I tell you, until heaven and earth pass away, not one letter, not one stroke of a letter, will pass from the law until all is accomplished” (Matt 5:17-18). And then follows strict instructions to those who follow Jesus, to ensure that they keep all the commandments, and ensure they do not break any of them (5:19).

So righteousness means living in accord with the Law, obeying all the requirements that it sets out, keeping all the commandments in fine detail. That is why Jesus instructs his followers to be the “salt of the earth” (5:13), the “light of the world” (5:14), so that others “may see your good works” (5:16). This means, always living in a way that bears “good fruit” (7:17), doing “the will of the Father” (7:21), listening to the words which Jesus speaks and acting on them diligently (7:24). Giving alms, praying faithfully, and fasting regularly, are offered as three key ways by which this righteous way of living will be manifest (6:1-18).

There can be no doubt that, in the book of origins, Jesus is intensely, rigorously, Jewish, scrupulously upholding the Law in every tiny detail in the way that he understands it to apply. And righteousness is at the centre of that way of life.

The concept of righteousness is thoroughly Jewish in origin. It is closely linked with the demand for justice. Patriarchal stories remember Noah as a righteous man (Gen 6:9) and recall that Abraham was accounted as righteous by God (Gen 15:6); Ezekiel adds Daniel and Job to this list (Ezek 14:14). A number of psalms make the claim that God is just and righteous by nature and in action (Ps 7:11; 116:5; 119:137, 144; 129:4; see also Isa 5:16; 11:3–5; 24:16; 45:21) and proverbs were collected to inform people of the ways to live righteously and with justice (for instance, Prov 10:11–13:25).

Various prophetic voices regularly called for justice and righteousness within Israel (Isa 1:24–28; 26:7–9; 32:16–17; 45:8; 61:10–11; Jer 22:3; 23:5–6; Ezek 3:20–21; 18:5–9; Dan 9:24; Hos 10:12; Amos 5:20; Hab 2:4; Zeph 2:3). Malachi envisages a book in which the names of the righteous will be written as the “special possession” of God (Mal 3:16–18).

The central catchcry of Amos, “let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream” (5:24), exemplifies the desires of faithful Israelites in ages past and is carried over into the hopes of faithful Jews in our own times.

And this word righteousness appears frequently in New Testament books (all four Gospels, Acts, most of the letters of Paul, and the letters to the Hebrews, and from James, Peter and John). And in many of these occurrences, it can equally validly be translated as justice. The two terms become interchangeable: living in a righteous way means living in a manner that prioritises justice.

Perhaps we would do better, in English, to render the Hebrew word tsdeqah, and the corresponding Greek word dikaiosune, as something like righteous-justice. The two words, in English, tend to pint us in different directions—righteousness has a personal orientation, justice refers to the way society operates. In Hebrew, and in Greek, the words overlap because those categories of personal and societal were not clearly distinguished and separated.

It was the Torah, the Law of Moses, which was at the heart of this desire for righteous-justice. Living in accordance with the prescriptions of a holy God meant leading a life of righteous-justice. The teachings of Jesus which are recorded in Matthew’s Gospel are both grounded in a commitment to Torah, and developed in accordance with Jewish understandings of a faithful life. Obedience to the Law essentially meant living a just life, a life of righteousness, in every aspect of life.

Indeed, there is a cluster of terms that sat at the heart of traditional Jewish piety at the time of Jesus. The terms righteous-justice and lawlessness, along with the devout and the ungodly, were common in sectarian language of the late Second Temple period. Use of such language was aimed at validating the position of the writer (and the writer’s community) in opposition to other positions.

We find that righteous-justice is a key term for defining the self-identity of the sectarian communities which produced various Jewish documents 4 Ezra (7:17, 49–51; 8:55–58), 2 Baruch (15:7–8; 85:3–5), 1 Enoch (94:1, 4–5; 96:1; 99:1–3; 95:6–7), and the Psalms of Solomon (4:8; 13:6–9; 15:6–9). In each of these writings, usually within the same sentences, the terms “sinners”, “ungodly” and “lawless” are used to define those outside the community.

In similar fashion, the Dead Sea Scrolls define their community as one marked by righteous-justice (Community Rule 3, 9; Commentary on Habbakuk 8), in distinction from outsiders who are “the wicked” (Damascus Rule 4) and “the children of falsehood” (Community Rule 3). The struggle between the various sectarian communities and those in power was couched in very black-and-white terms.

The same cluster of terms is to be found in the book of origins. To live by righteous-justice is a key defining feature of faithful disciples (10:41; 13:17, 43; 25:37, 46), and righteous-justice is the keynote of Jesus’ ministry (3:15; 5:6, 10, 20; 6:33). By contrast, those who are unfaithful are depicted as “lawless” (7:23; 13:41; 23:28; 24:10–12). This Gospel thus draws the same distinction between its members and outsiders, as is found in other Jewish sectarian documents of the time.

To be righteous means to adhere to the Law. To adhere to the Law means to live a just life. This is what Jesus taught, and this is how Jesus lived, as we find reported in the book of origins. And so, the whole Sermon on the Mount is included in this book as a challenging statement of what it means to be a faithful follower of Jesus, keeping the Law in every respect, living with an excess of righteous-justice.

See also

https://johntsquires.com/2020/01/23/repentance-for-the-kingdom-matt-4/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/12/27/reading-matthews-gospel-alongside-the-hebrew-scriptures-exploring-matthew-2/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/12/21/a-young-woman-a-virgin-pregnant-about-to-give-birth-isa-714-in-matt-123/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/12/11/the-origins-of-jesus-in-the-book-of-origins-matthew-1/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/12/19/descended-from-david-according-to-the-flesh-rom-1/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/12/17/now-the-birth-of-jesus-the-messiah-took-place-in-this-way-matthew-1/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/12/04/for-our-instruction-that-we-might-have-hope-rom-15-isa-11-matt-3/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/11/28/leaving-luke-meeting-matthew/