“Follow me and I will make you fish for people”, Jesus tells some fishermen, in the Gospel offered by the lectionary for this coming Sunday (Mark 1:14–20, the Third Sunday after Epiphany). Perhaps because of the fishing theme, the lectionary pairs with it an excerpt from what must be the best-known fish story of Hebrew Scripture—that of Jonah.

Although, curiously, in what the lectionary offers, we don’t get the actual fish scene (Jonah 1:17—2:10). What we have is the “second chance” that Jonah has, to act as a real prophet. Rather than running away to sea (1:3), in the opposite direction from where he had been commanded to go, Jonah this time accepts the call from God, “get up, go to Nineveh, that great city, and proclaim to it the message that I tell you” (3:2).

What we hear in this chapter is the simple report of Jonah’s fiery message—“forty days more, and Nineveh shall be overthrown!”—and the immediate response, “the people of Nineveh believed God; they proclaimed a fast, and everyone, great and small, put on sackcloth” (3:4–5).

The book of Jonah, of course, is one great comic burlesque from beginning to end. In the midst of the accounts of prophets who heard the call of God, hesitated, and then accede to the divine pressure to take up the challenge and declare the judgement of the Lord to a sinful people, we have Jonah.

We have Jonah, who when he is commanded to go northeast to Nineveh, immediately flees in the opposite direction, boarding a ship that was headed west across the Mediterranean Sea, to Tarshish, “away from the presence of the Lord” (Jon 1:3).

We have Jonah, escaping from the command of the Lord, only to find that “the Lord hurled a great wind upon the sea”—so all the cargo on the ship is thrown overboard. We have Jonah, blissfully sleeping, apparently unaware of the great storm (as if!), interrogated by the sailors, eventually offering himself as a sacrifice to save the boat (1:12). A comic hero, indeed.

So the sailors try in vain to save the ship; but realising that this is futile, they throw Jonah into the sea—and immediately “the sea ceased from its raging” (1:15). Then, adding further incredulity to the unbelievable narrative, “the Lord provided a large fish to swallow up Jonah” (1:17). The three days and three nights that he spends “in the belly of the fish” before he is vomited onto dry land (2:10) add to the comic exaggeration. You can just imagine the ancient audiences rolling with laughter.

The psalm that Jonah prays from inside the fish (2:1–9) and the successful venture to Nineveh, where even the king “removed his robe, covered himself with sackcloth, and sat in ashes” (3:1–10) apparently demonstrate that Jonah should have obeyed the command of the Lord in the first place. However, Jonah’s response continues the exaggerated response of a burlesque character; “this was displeasing to Jonah, and he became angry” (4:1).

Jonah’s resentment and his plea for God to take his life (4:2–4) and his patient waiting for God to act (4:5) lead to yet another comic-book scene, as a bush grows and then is eaten by a worm and Jonah is assaulted by “a sultry east wind” (4:6–8). The closing words of the book pose a rhetorical question to Jonah (4:9–11) which infers that God has every right to be concerned about the lives of pagans in Nineveh. The last laugh is on Jonah; indeed, he has given his readers many good laughs throughout the whole story!

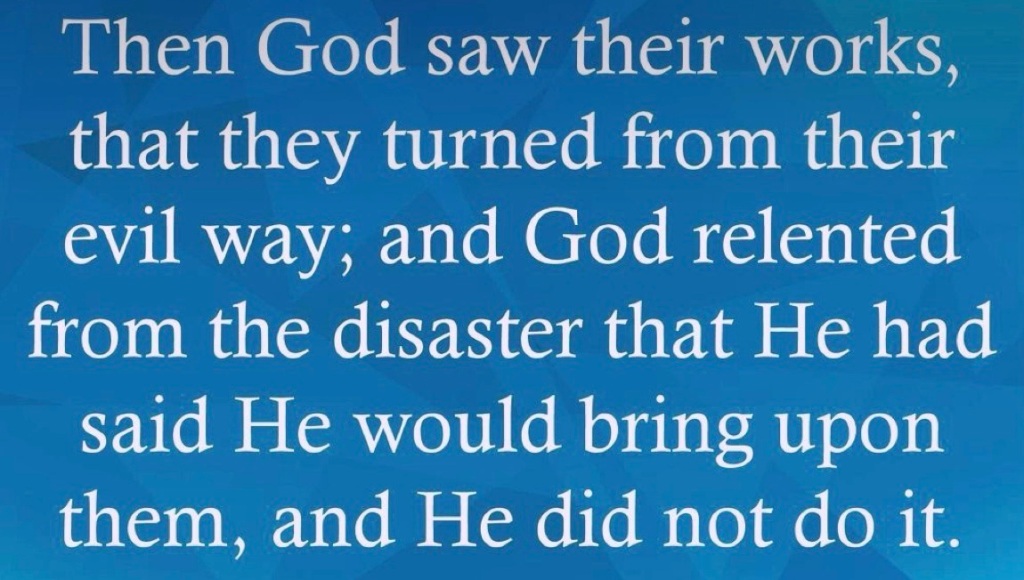

However, the section offered by the lectionary does provide us with a matter warranting serious thought. In the midst of the comedy, the narrator reports that when God saw the repentance of the people of Nineveh, “God changed his mind about the calamity that he had said he would bring upon them; and he did not do it” (3:10).

God changed God’s mind. That is a striking statement! If we read from the perspective of classic Christian theology, then we read with the expectation that God knows everything (and thus would have known of Jonah’s initial resistance and subsequent obedience); that God is in control of everything (and thus would have engineered the vomiting fish and the sheepishly-repentant prophet); and that God has sovereign power to determine the course of events (and thus would have planned well in advance the repentance of the Ninevites).

So a classic theological approach is somewhat stymied, I would have thought, by the comment that “God changed God’s mind”. By contrast, reading the story as part of Hebrew Scripture (rather than from the lens of systematic theological thinking) means that we can recognise that there is a vigorous “debate” being undertaken amongst the various authors of different parts of scripture on precisely this issue.

On the one hand, some texts make it quite clear that God was understood to have been averse to any change of mind; once God had decided, that was the end of the matter. M

In the historical narrative of the story of Israel, when Samuel informs Saul that David will be anointed as king, he asserts that “the Glory of Israel will not recant or change his mind; for he is not a mortal, that he should change his mind” (1 Sam 15:29). In an earlier book in that extended narrative, Balaam tells Barak that “God is not a human being, that he should lie, or a mortal, that he should change his mind. Has he promised, and will he not do it? Has he spoken, and will he not fulfill it” (Num 23:19).

And in a well-known royal psalm (which Jesus was said to have quoted), the psalmist declares that “the Lord has sworn and will not change his mind, ‘You are a priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek’” (Ps 110:4, quoted at Heb 7:21). This idea of the unchanging deity whose mind remains resolutely fixed is also reflected in the oft-quoted line from Hebrews, “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever” (Heb 13:8).

On the other hand, other biblical authors recount stories in which God is, indeed, capable of changing God’s mind. God has a change of mind in the story of Moses and the Golden Calf, narrated in Exodus 32. Moses is appalled when he discovers that the Israelites, in his absence, have created an idol—a Golden Calf—and have thereby breached one of the Ten Words that are at the heart of the covenant he has made with God. Moses mounts a passionate plea to God, asking for the divine fury to be turned away from the sinful people.

Invoking the covenant made with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, Moses implores God to “turn from your fierce wrath; change your mind and do not bring disaster on your people” (Exod 32:12–13). So the Lord repented (v.14), and Moses took revenge on the people (vv.19–20); he burned the idol and ground it into water, and made the people drink it. God clearly has a change of mind in this story.

God also has a change of mind in Genesis. Abraham is instructed to take his son, Isaac, and “offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you” (Gen 22:2). Abraham is obedient, and “reached out his hand and took the knife to kill his son”; but an angel of the Lord called to him from heaven and restrained him (Gen 22:11–12), providing instead “a ram, caught in a thicket by its horns” as the sacrificial victim (Gen 22:13). Clearly, God changed God’s mind.

The prophet Amos speaks two short oracles in which God was planning to judge the people, sending a plague of locusts (Amos 7:1) and then a shower of fire (Amos 7:4). In both instances, after petitions from the prophet, “the Lord relented concerning this; ‘it shall not be,’ said the Lord” (Amos 7:3, 6).

And how many psalms contain petitions to the Lord, from faithful people, imploring God to change God’s mind? “O Lord, do not rebuke me in your anger, or discipline me in your wrath” (Ps 6:1); “rise up, O Lord; O God, lift up your hand; do not forget the oppressed” (Ps 10:12); “do not cast me away from your presence, and do not take your holy spirit from me” (Ps 51:11); “hear a just cause, O Lord; attend to my cry” (Ps 17:1).

One psalm presses the point with intensity: “do not let the flood sweep over me, or the deep swallow me up, or the Pit close its mouth over me; answer me, O Lord … turn to me; do not hide your face from your servant, for I am in distress—make haste to answer me” (Ps 69:15, 17). Another reflects on their situation with pathos, pleading, “do not cast me off in the time of old age; do not forsake me when my strength is spent” (Ps 71:9; see also vv.12, 18).

And in the longest psalm of all, Psalm 119, even though the psalmist notes that they are consistently faithful to Torah, yet the plea comes: “do not utterly forsake me” (v.8), “turn away the disgrace that I dread” (v.39), “I implore your favour with all my heart” (v.58), “how long must your servant endure? when will you judge those who persecute me?” (v.84), “look on my misery and rescue me … plead my cause and redeem me” (vv.153–54). This psalm, like so many psalms, is premised on the understanding that God will hear the passionate prayer of the psalmist and have a change of mind.

The prophet Jeremiah considers the possibility, and then affirms the actuality of God changing God’s mind. “At one moment I may declare concerning a nation or a kingdom, that I will pluck up and break down and destroy it”, he says, in the name of the Lord; “but if that nation, concerning which I have spoken, turns from its evil, I will change my mind about the disaster that I intended to bring on it. And at another moment I may declare concerning a nation or a kingdom that I will build and plant it, but if it does evil in my sight, not listening to my voice, then I will change my mind about the good that I had intended to do to it.” (Jer 17:7–10). The capacity for a change of mind is crystal clear here (and see also Jer 26:3, 13).

Later, Jeremiah tells of the prophet Micah of Moresheth, from the days of King Hezekiah of Judah, who threatened destruction for the city in his oracle. Jeremiah comments, “did he not fear the Lord and entreat the favour of the Lord, and did not the Lord change his mind about the disaster that he had pronounced against them?” (Jer 26:18–19).

So while the systematicians want to locate our knowledge of God and our relationship with God within the constraints of doctrines and structures and systems, those attending carefully to the biblical text will know that the witness of scripture is diverse and varied, and also that there are different points of view put forward within the pages of the Bible, about important matters—including, as we have seen, the capacity of God to have a change of mind. Some authors consider God can do this; others reject the possibility.

So what do you think?