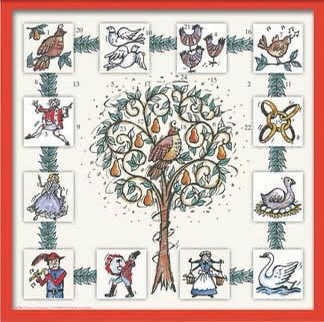

So, it is the night of Christmas Day, and it feels like it is all over—done and dusted, finished, put to bed. Hold it—not so fast!! This is only just the start. Christmas Day is just the first of twelve days of the Christmas season. You might have heard about those twelve days in the song, The Twelve Days of Christmas. This is an English Christmas Carol which is often sung in the lead up to Christmas. It actually belongs to the Christmas season—that is, the days on and after Christmas Day.

Now, some have claimed that this song had a pietistic purpose: a kind of sung catechism about the central features of the Christian Faith, put into code by Roman Catholics in England when their faith was outlawed. (One is Jesus, two symbolises the two testaments, three indicates faith, hope and love, four refers to the Gospels, five to the Books of Moses, ten to the Ten Commandments, twelve to the apostles, and so on …)

Nice theory, but there is no evidence at all that this was the case … and the origins of the theory go back no further than a speculation by a Canadian hymn writer in an article published in 1979. (And snopes.com agrees; you can read the detailed rebuttal at http://www.snopes.com/holidays/christmas/music/12days.asp)

The Twelve Days of the #twelvedaysofchristmas technically refer to the days from Christmas Day, the first day of Christmas, through to Twelfth Night. So the song should be sung from Christmas Day onwards. And the gifts that are given each day accumulate until the twelfth night, the evening before Epiphany, when gifts were given to Jesus by the Magi visiting from the east.

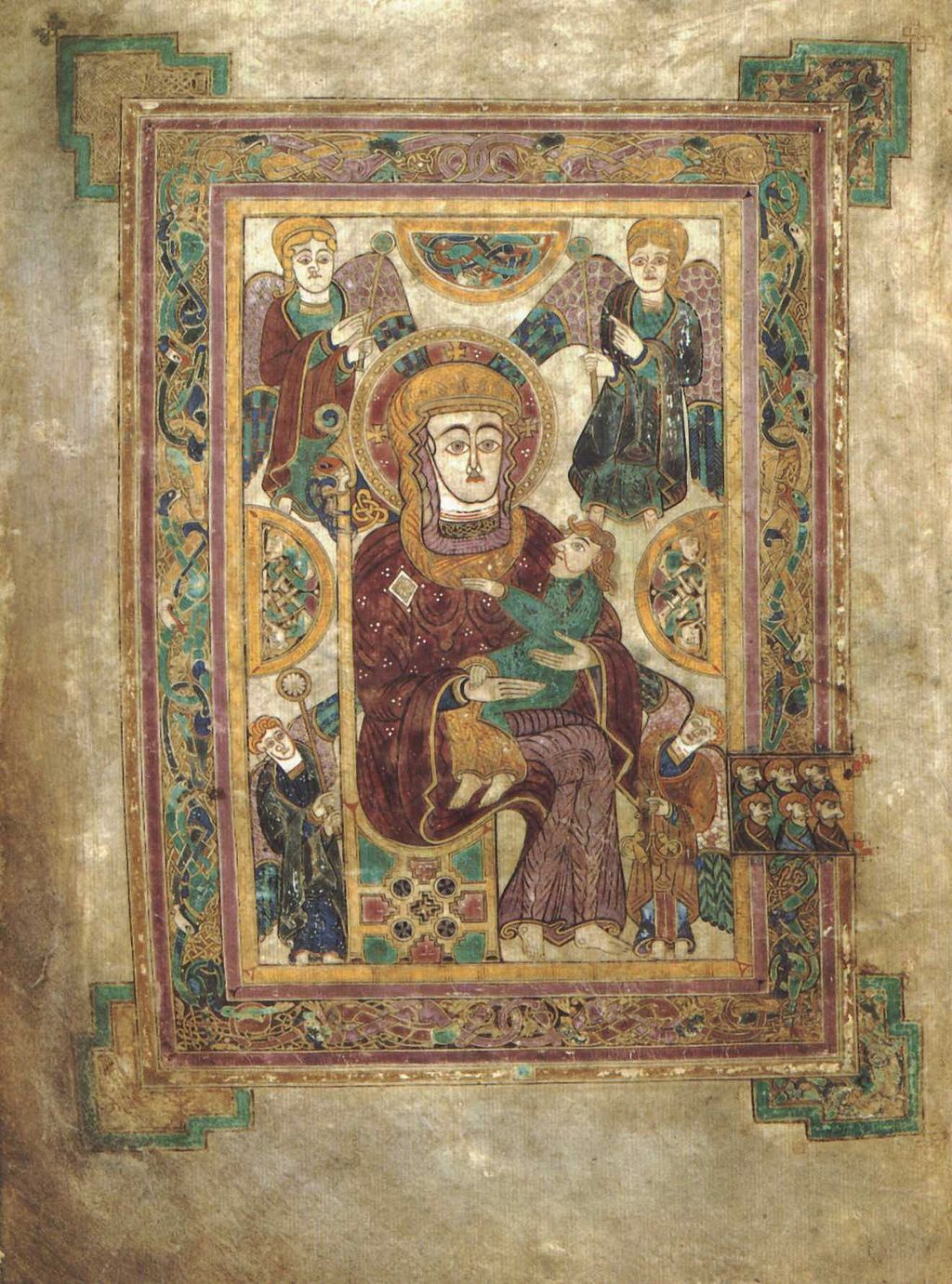

Professor Bruce Forbes writes that “In 567 the Council of Tours proclaimed that the entire period between Christmas and Epiphany should be considered part of the celebration, creating what became known as the twelve days of Christmas, or what the English, called Christmastide. On the last of the twelve days, called Twelfth Night, various cultures developed a wide range of additional special festivities. The variation extends even to the issue of how to count the days.” (Christmas: A Candid History, 2008; see p. 27).

Forbes also notes that there are divergent chronologies at work in different parts of the church: “If Christmas Day is the first of the twelve days, then Twelfth Night would be on January 5, the eve of Epiphany. If December 26, the day after Christmas, is the first day, then Twelfth Night falls on January 6, the evening of Epiphany itself.”

There’s a suggestion that The Twelve Days of Christmas song was originally sung in French . . . or, at least, that the line for the First Day originally included both French and English terms for the bird; thus, “partridge” (in English, and then in French, “perdrix” (pronounced per-dree) . . . which makes no sense, really; but this is a Christmas Carol, and such songs don’t really have to make sense, do they?

On the Second Day, two turtledoves are to be given. But for what purpose? Since this song relates to Christmas, can we assume that there is some religious or spiritual significance with this gift??

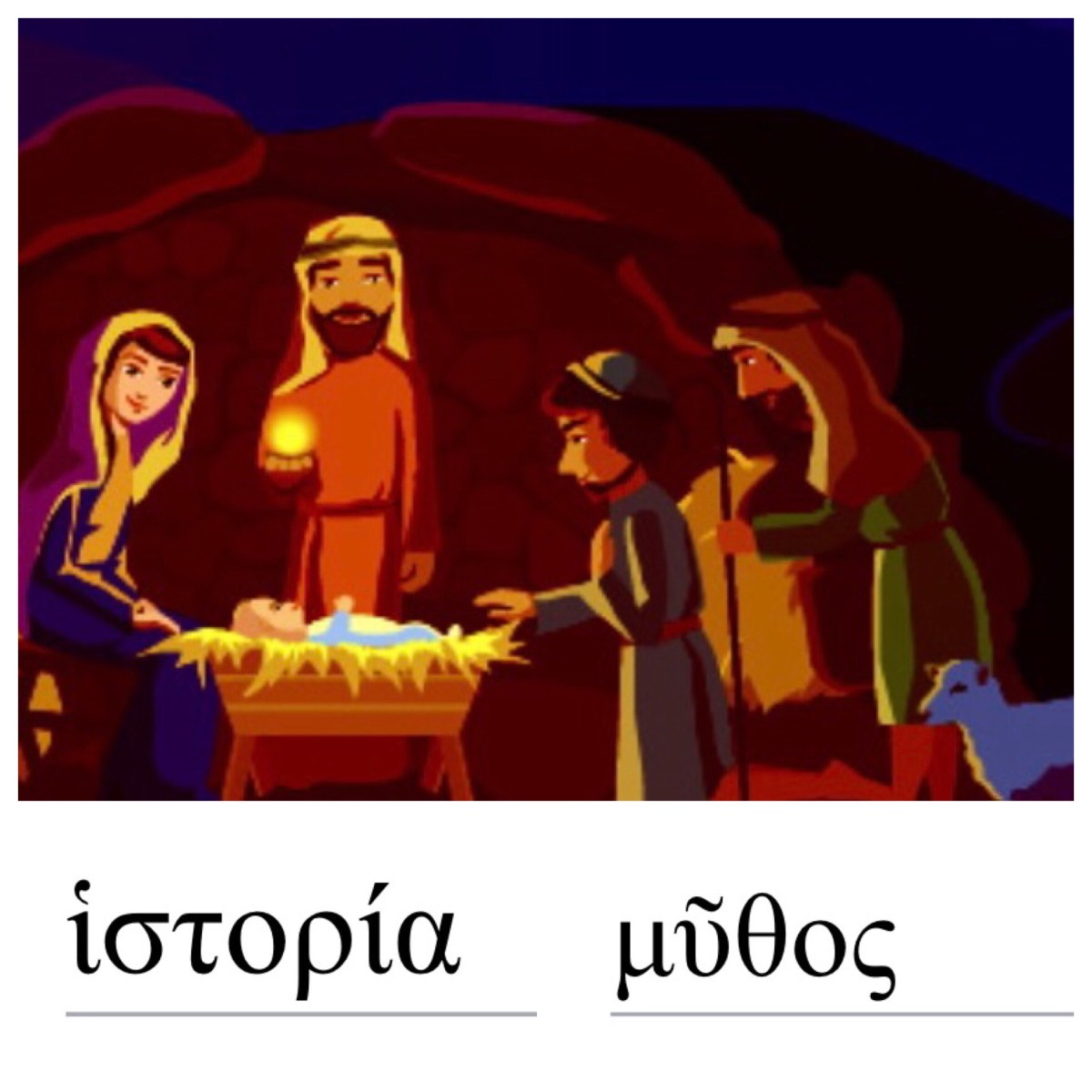

Turtle doves could be offered as a sin-offering (Lev 5:7). Is this why they were given? Or perhaps, as the alternate offering for a poor woman, seeking purification after giving birth (Lev 12:8)? This at least links in to the Christmas story (at Luke 2:24), which is what the song is supposed to be about! But it does seem like a long shot …

So, what about as a guilt-offering when cleansing a leper (Lev 14:22)? Or maybe for a Nazirite who has touched a corpse (Num 6:9)? Or as a means of cleansing after sexual discharge (Lev 15:14)? Or maybe the text is multivalent, and we are supposed to bring all of these allusions to mind. Because we know our Bible so well. And we know this is meant to be symbolic. Eh?

Next, on Day Three, the gift to be given is three French hens. Some suggest they are Faith, Hope and Charity, the key Theological Virtues. But only three? There are actually four types of French Hens (Faverolles, La Fleche, Crevecoeurs and Marans). So do we know which one of the four missed out on its moment of glory in this Christmas carol? It’s a worry.

On Day Four, four birds form the gift. Ah, but what type of birds? Calling birds? So you might think. But older versions of the song identify them as Colly Birds. Which are … …??? A colly bird is a black bird. A coal mine is called a colliery, so ‘colly’ or ‘collie’ is a derivation of this and means black like coal. So, no more whitewashing, let’s sing “four black birds”, and be clear about it, eh?

And … while we are at it … Day Five: Five Golden Rings? But they are surrounded by flocks of birds (swans, geese, colly birds, hens de la France, turtle doves, and a partridge). Rings are out of place. So, it is believed that this verse originally referred not to jewellery but to ring-necked birds such as the ring-necked pheasant. So, let’s now sing: “five ring-necked birds”! Context is everything!

The sixth of the #twelvedaysofchristmas is the midpoint of the 12 days, when we can look back on the story of Christmas (the birth and the shepherds), and forward to the story of Epiphany (the visit of the Magi). The gift for the Sixth Day focusses on new life: six geese a-laying.

It is said that, while chickens lay eggs regularly (usually each day ), geese only lay 30-50 eggs a year. This means they are a less productive bird to keep. It takes longer to increase the size of the flock for meat production. And their eggs are very high in cholesterol. Was this a wise gift? (Of course, you may well score the goose that lays the golden egg.)

On Day Seven, the gift is seven swans a-swimming. Well, yes; that’s what swans do. But who in their right might give this as a gift? Where would they all be put so that they could keep swimming? In a huge bathtub? This is quite unrealistic. Anyway, I guess it proves that the carol was not written by a football-mad fanatic. (They would have had swans kicking goals.)

On Day Eight, we are exhorted to give eight maids a-milking. In older English, to “go a-milking” could mean to ask a woman for her hand in marriage; OR to ask a woman to go “for a roll in the hay”, as it were. Is this Christmas carol concealing a reference to illicit sexual encounters? And does that make it more interesting than just getting some milk in order to make some cheese?

Next: Day Nine. Nine ladies dancing. Liturgical dances, I presume? In explore the significance of these ladies, I am somewhat stumped. Any clues, anyone?

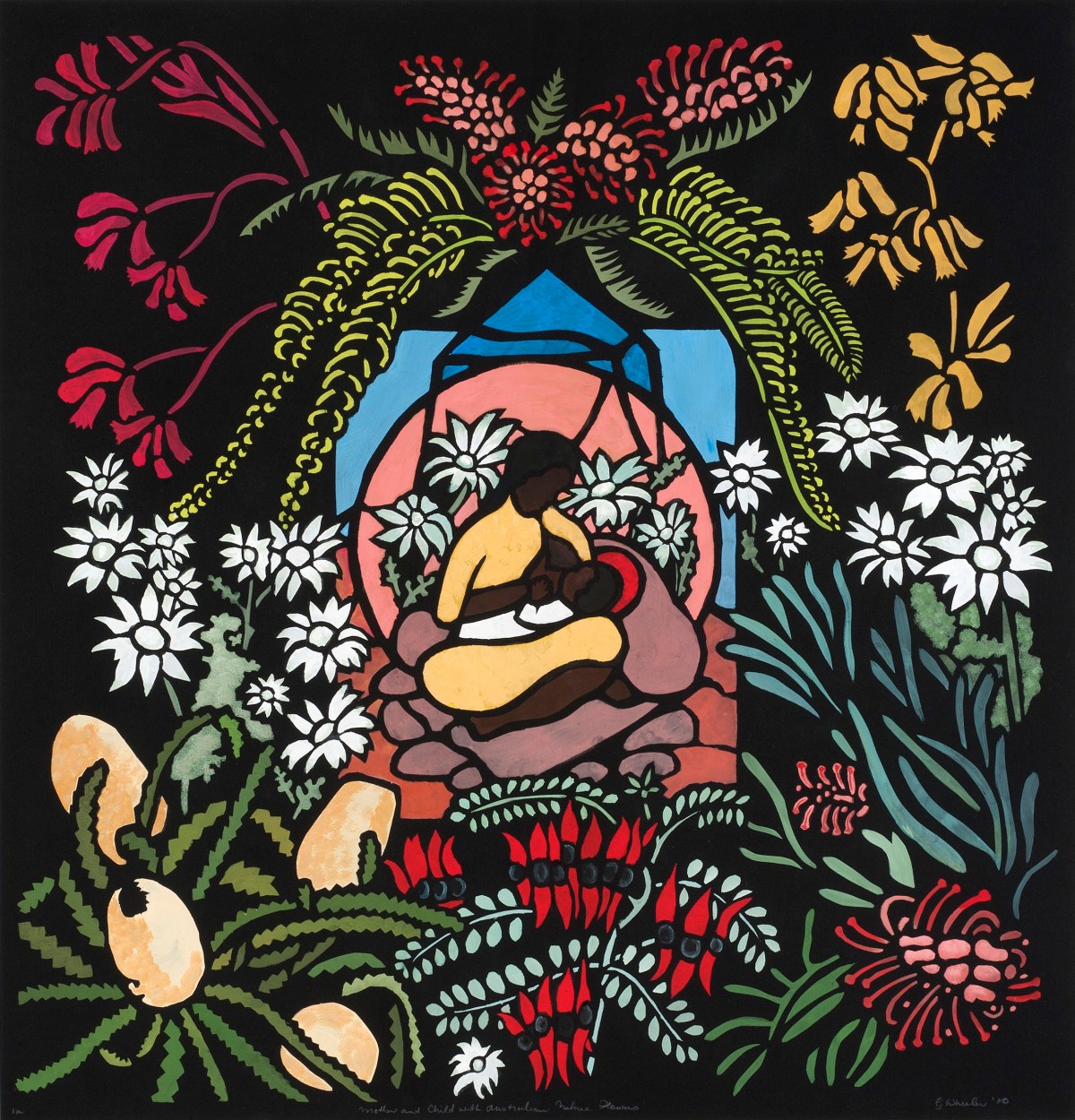

Meanwhile, I am starting to compile my list of ‘not relevant in Australia’ secular Christmas carols. Because here, downunder, we are in the midst of summer—not winter, as all the upover northern hemisphere Christmas songs assume. So, not relevant to downunder would include: Anything with snow, for a start. And bells. And holly. And fir trees. And … well, the possibilities are endless.

On Day Ten, the gift is to be ten Lords a-leaping. Alliteration, indeed; but why leaping? Perhaps there is a textual transmission problem here. Maybe it should be: Lords a-leasing? (what to do with their huge old castles and manors)? Or Lords a-sleeping? (in the upper chamber of the British parliament)? Or perhaps Lords a-weeping? (at the decline of their much- loved aristocratic powers). Who knows?

Which brings us to the eleventh day of (the season of) Christmas. On Day Eleven we meet eleven pipers piping. So perhaps this comes from a Scottish variant (like day one comes from the French version). Perhaps the Scots packed their song full of food? In this, the gifts would include twelve alka seltsers, eleven Blue Lagoons, ten creme de menthe, nine vodka and limes, eight nips of whisky, seven rum and cokes, six Carlsberg specials…you get the picture? (Yes, I know, this is becoming quite speculative!!)

Or — does the Scottish reference (bagpipes) mean that I should refer to the crackpot theory that this whole carol was a coded reference to the right of Bonny Prince Charlie to regain the British throne? Yegods … …

But I do note that, in other versions, there are eleven ladies spinning, eleven ladies dancing, eleven lads a-louping, eleven bulls a-beating, and eleven badgers baiting!! Make of them, what you will.

And then, we come to the ultimate (last) of the #twelvedaysofchristmas. Day Twelve. Twelve drummers drumming.

Since the gifts are cumulative, and repeated on each day, on Day Twelve we actually have drummers drumming, along with piping pipers, leaping lords, bleating cows, tapping toes, shuffling shoes, a horde of aviary escapees, and the whole schemozzle. 78 gifts in all (count them) just on this last, twelfth, day. Presumably the others gifts from earlier days are still there. That’s one heck of a menagerie!! It’s all too loud, I think — and the incessant fights amongst all those squawking birds! Oh dear; time for a doze, instead.

The evening of Day Twelve is thus Twelfth Night. The day after is Epiphany, a day to celebrate the coming of the magi to the infant Jesus. Time, indeed, to rest—when you get there. But, for the moment, there’s some geese to be sourced. And some drummers. And milkmaids … and Lords (Lords??) … and ………….

*****

See also https://claudemariottini.com/2022/12/26/the-12-days-of-christmas/