The Uniting Church Basis of Union declares that we are followers of Jesus, and that in Jesus, God made a representative beginning of a new order of righteousness and love. It is righteousness and love which is at the heart of God, and it is righteousness and love which is at the centre of the work that Jesus undertakes. That is the perpetual dynamic that expresses the essential nature of God—and, indeed, that describes the demands and requirements of living with others in society.

We have considered prophets from Miriam in the story of the Exodus, through Deborah in the prime of the judges, through the time of the divided kingdoms (Amos, Hosea, Isaiah, Micah, and others), after the conquest of the northern kingdom, as the southern kingdom continues (Huldah and Jeremiah) into the time of exile in Babylon (Jeremiah, still, as well as Ezekiel and Second Isaiah), and on into the return to the land after exile (Third Isaiah, Haggai, and Zechariah). Today we move beyond those periods into the ongoing life of post-exiled Israel.

Each of these prophets wrestles with this dynamic; how does God express deep seated covenant love to show his mercy, whilst holding the covenant people to the terms of their agreement, living in a just and righteous manner, and executing punishment for their failure to uphold what that covenant requires. Righteousness and mercy, judgement and grace, belong together in an unbroken whole within God. That is the dynamic that each prophet is aware of, and that each prophet articulates in the oracles the speak to their people.

As the later Jewish writer Ben Sirach, a scribe and sage in the 2nd century BCE, wrote: “Do not say, ‘His mercy is great, he will forgive the multitude of my sins,’ for both mercy and wrath are with him, and his anger will rest on sinners” (Sir 5:6). That phrase, “both mercy and wrath are with him”, articulates the tensions inherent in the developing Jewish understanding of God.

The final group of prophets that we consider now are also grappling with that same dynamic. The tension between mercy and anger, between gracious forgiveness and fierce punishment, between righteousness and love, runs through these books. How do they deal with this?

*****

The prophet Malachi was active after the Babylonian Exile, soon after Haggai and Zechariah had been prophesying. The city and temple had been fully restored and worship was now active in the temple. In this context, Malachi called the people to repentance, starting with the priests, whom he attacks for their corruption (1:6–2:9); “the lips of a priest should guard knowledge, and people should seek instruction from his mouth, for he is the messenger of the Lord of hosts; but you have turned aside from the way; you have caused many to stumble by your instruction; you have corrupted the covenant of Levi, says the Lord of hosts” (2:8–9).

He then turns to the religious profanity of the people; “Judah has been faithless, and abomination has been committed in Israel and in Jerusalem; for Judah has profaned the sanctuary of the Lord, which he loves, and has married the daughter of a foreign god” (2:11), and instructs them to “take heed to yourselves and do not be faithless” (2:16). God threatens punishment in graphic terms: “I will rebuke your offspring, and spread dung on your faces, the dung of your offerings, and I will put you out of my presence” (2:3).

Malachi then identifies a range of ways by which social inequities are practised; God threatens, “I will be swift to bear witness against the sorcerers, against the adulterers, against those who swear falsely, against those who oppress the hired workers in their wages, the widow and the orphan, against those who thrust aside the alien, and do not fear me, says the Lord of hosts” (3:5). He notes that people regularly shortchange the Lord with incomplete tithes (3:8–15); rectifying this will result in blessings from God (3:10–12).

The prophet looks to the coming of a messenger from God (3:1) who will bring judgment “like a refiner’s fire and like fullers’ soap; he will sit as a refiner and purifier of silver, and he will purify the descendants of Levi and refine them like gold and silver, until they present offerings to the Lord in righteousness” (3:2–3).

The fierce imagery continues with a description of “the day [which] is coming, burning like an oven, when all the arrogant and all evildoers will be stubble; the day that comes shall burn them up, says the Lord of hosts, so that it will leave them neither root nor branch” (4:1). The motif of “the day” has run through the prophets, from before the exile (Amos 5:18–20; Isa 2:12, 17; 13:6–8; 34:8; Zeph 1:7, 14–15), during the years of exile (Jer 35:32–33; 46:10), and on into the years after the return from exile (Joel 2:1–3, 30–31).

What is required of the people is clear: “remember the teaching of my servant Moses, the statutes and ordinances that I commanded him at Horeb for all Israel” (4:4). Adherence to the covenant undergirds the claims of this prophet, as indeed it does with each prophet in Israel.

This short book ends with a memorable prophecy from Malachi: “Lo, I will send you the prophet Elijah before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes. He will turn the hearts of parents to their children and the hearts of children to their parents, so that I will not come and strike the land with a curse.” (4:5–6). These words are picked up in the Gospel portrayals of John the Baptist as the returning Elijah (Matt 17:9–13; Luke 1:17), turning the hearts of people so that they might receive the promise offers by Jesus. Whether Malachi himself understood these words to point to John and Jesus, of course, is somewhat dubious.

*****

The final two “minor prophets”, Jonah and Joel, are hard to locate within the timeline of Israel. Whether Jonah was an actual historical figure is hotly debated; in fact, the four chapters of this book tell a rollicking good tale, that makes us suspect that it was, in fact, “just a story”, rather than actual history.

The large city in this book is Nineveh (Jon 1:2; 3:1–10); it was the capital of Assyria (2 Ki 19:36; Isa 37:37) and we learn at the end of the story of Jonah that it had a huge population of more than 120,000 people. The story thus appears to be set during the period of Assyrian ascendancy, in the 8th century BCE. But many of the literary characteristics of this book reflect a later period, perhaps even a post- explicitly time.

It is true that 2 Kings 14:25 mentions that God speaks through “Jonah son of Amittai, the prophet” during the time of Jeroboam II (about 793–753 B.C.), but this was a time before Nineveh was the capital of Assyria. There is no other indication that this individual was the prophet whose story is told in the book of Jonah, for it does not provide any specific dating; nor does the mention of Jonah in 2 Kings indicate how he exercised his prophetic role.

The charge that Jonah is given is a stock standard prophetic charge: “go to Nineveh, that great city, and cry out against it; for their wickedness has come up before me” (1:2; cf. Amos 1:3; Isa 6:9–13; Jer 1:9–10; Ezek 2:3–4; 3:18–21; Nah 1:2–3; Hab 2:2–5; Zeph 1:2–6). The response of Jonah is like some of those prophets: an initial reluctance to accept the charge (Isa 6:5; Jer 1:6; and see Moses at Exod 3:11, 13; 4:1, 10).

However, whilst other prophets accede to the divine pressure to take up the challenge and declare the judgement of the Lord to a sinful people, Jonah holds fast to his reticence—when commanded to go northeast to Nineveh, he immediately flees in the opposite direction, boarding a ship that was headed west across the Mediterranean Sea, to Tarshish, “away from the presence of the Lord” (Jon 1:3).

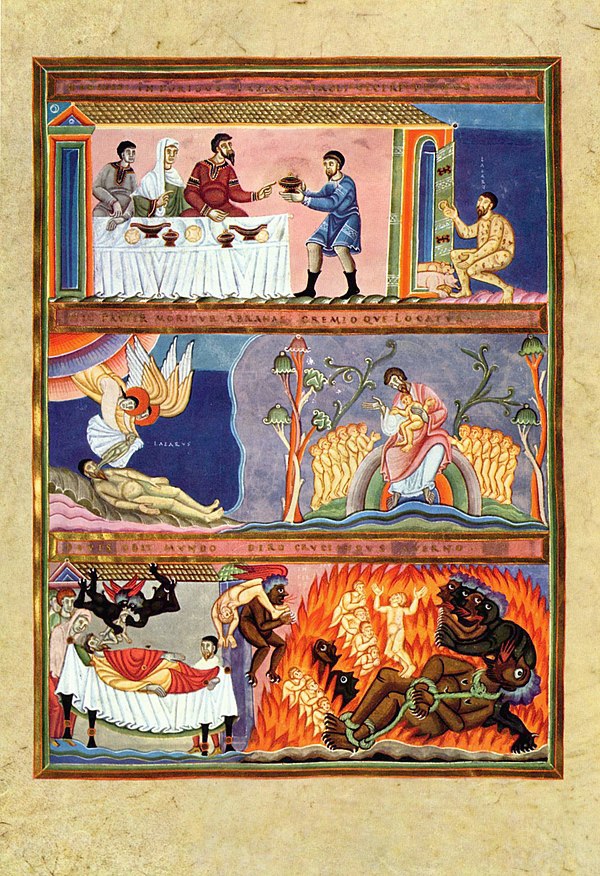

The escape of Jonah from the command of the Lord may be deeply troubling; but the narrative spins the story into burlesque, as “the Lord hurled a great wind upon the sea”, all the cargo on the ship is thrown overboard, and then Jonah (blissfully sleeping, apparently unaware of the great storm—as if!) is interrogated by the sailors, and eventually offers himself as a sacrifice to save the boat (1:12).

The sailors try in vain to save the ship; realising that this is futile, they throw Jonah into the sea—and immediately “the sea ceased from its raging” (1:15). Then, adding further incredulity to the unbelievable narrative, “the Lord provided a large fish to swallow up Jonah” (1:17). The three days and three nights that he spends “in the belly of the fish” before he is vomited onto dry land (2:10) add to the comic exaggeration.

The psalm that Jonah prays from inside the fish (2:1–9) and the successful venture to Nineveh, where even the king “removed his robe, covered himself with sackcloth, and sat in ashes” (3:1–10) apparently demonstrate that Jonah should have obeyed the command of the Lord in the first place. However, Jonah’s response continues the exaggerated response of a burlesque character; “this was displeasing to Jonah, and he became angry” (4:1).

Jonah’s resentment and his plea for God to take his life (4:2–4) and his patient waiting for God to act (4:5) lead to yet another comic-book scene, as a bush grows and then is eaten by a worm and Jonah is assaulted by “a sultry east wind” (4:6–8). The closing words of the book pose a rhetorical question to Jonah (4:9–11) which infers that God has every right to be concerned about the lives of pagans in Nineveh. The last laugh is on Jonah; indeed, he has given his readers many good laughs throughout the whole story!

******

The final prophet for us to consider is Joel, who speaks words of lament and calls for repentance amongst the people of Judah. Nothing in this book provides any clues as to the time when Joel was active. The identification of the prophet as “son of Pethuel” (Joel 1:1) gives no clue, as Pethuel appears nowhere else in the Hebrew Scriptures—indeed, the name Joel, itself appears nowhere else. The name appears to combine the divine names of Jah and El, suggesting that it may be a symbolic creation. Was Joel an historical person?

Joel calls on the “ministers of God” to “put on sackcloth and lament” (1:13); this reminds us of the response of the pagans in Nineveh (Jonah 3), whilst his remonstrations that “the day of the Lord is near” (1:15) echoes the motif of “the day” already sounded by other prophets (Amos 5:18–20; Isa 2:12, 17; 13:6–8; 34:8; Zeph 1:7, 14–15; Jer 35:32–33; 46:10).

This day forms the centrepiece of Joel’s undated prophecies, as he describes that day as “a day of darkness and gloom, a day of clouds and thick darkness!” (Joel 2:2), when “the earth quakes before them, the heavens tremble, the sun and the moon are darkened, and the stars withdraw their shining” (2:10). He describes the response of the people “in anguish, all faces grow pale” (2:6).

However, Joel adheres to the constant thread running through Hebrew Scriptures, that the Lord is “gracious and merciful, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love, and relents from punishing” (2:13). Because of this, he yearns for the people to “turn with all your heart, with fasting, with weeping, and with mourning” (2:12), sensing that there might be hope of restitution for the people.

Joel calls for the people to gather (2:15–16); the oracle that follows paints a picture of abundance and blessing (2:18–27), affirming that “my people shall never again be put to shame” (2:27).

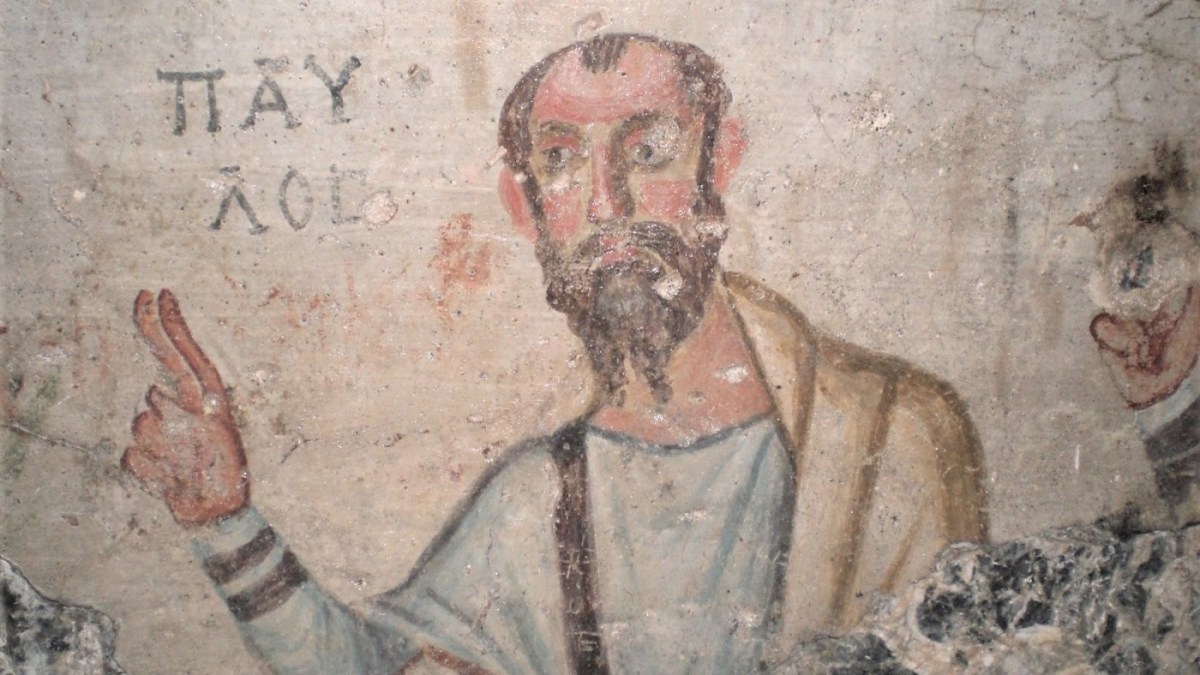

The prophet then speaks words which have been given a central place in the later story of the Christian church, when he foreshadows that the blessings of God will be manifest through the outpouring of the spirit: “your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, your old men shall dream dreams, and your young men shall see visions; even on the male and female slaves, in those days, I will pour out my spirit” (2:28–29). This promise is specifically for “all flesh”; this universal vision informs the whole outward impulse of the movement of followers of Jesus, after the day of Pentecost, which Peter interprets as being a fulfilment of this prophecy (Acts 2:14–21).

The day of the Lord that is then envisaged (2:31) will signal a significant reversal for Israel. The Lord laughs at other nations (3:1–8), a reversal that pivots on a turn from despair to hope, from the threats of judgement to a glorious future (3:9–21). Joel repeats the irenic vision of swords being beaten into ploughshares (3:10; see Isa 2:4; Mic 4:3); he sees a ripe harvest (3:13), the land will drip with sweet wine, and there will be milk and water in abundance (3:18). The voice of the Lord “roars from Zion, and utters his voice from Jerusalem, and the heavens and the earth shake” (3:16; cf the similar pronouncement of Amos at Am 1:2; 3:8).

The last word of this book, “the Lord dwells on Zion” (3:21), provides assurance and certainty for the future. These words of hope promises a peaceful future for the nation. When Joel might have been speaking these words cannot be definitively determined; it could have been under the Assyrian threat, during the Babylonian dominance, in the time of exile, or after the return to the land—the promise of hope holds good in each of these scenarios.

********

See also