Next Sunday is the second Sunday in the season of Epiphany. The word epiphany refers to the manifesting of light, the shining forth of revelation. It is applied to this season, which follows on from Christmas, and is initiated by the story of “the star in the east” told in Matthew 2:1-12.

The birth of Jesus, and the story of the Magi following the star, signals the early Christian belief that God was acting in a new way through this child. The Magi come from the east, following the star, to pay homage to the infant Jesus. Light is of symbolic significance in this story, as is the theological claim that the child Jesus provides a revelation of God.

Throughout the five Sundays of Epiphany, as indeed throughout much of the year, we hear and read the stories contained in the earliest account of Jesus, the beginning of the good news of Jesus, which we know more typically as the Gospel according to Mark. During these five Sundays, we will hear and read most of the opening chapter of this Gospel (with a detour this coming Sunday to the first chapter of John’s Gospel).

Alongside these Gospel excerpts, the passages set by the lectionary from the Hebrew Scriptures for the season of Epiphany have been carefully chosen. These passages illuminate the message of the Gospel which we hear each week from the New Testament, as we celebrate Christ as the light that comes into the world, illuminating and enlightening.

This week, we hear the story of the call of Samuel to be a prophet of the Lord (1 Sam 3:1–20). We may think of prophets as loud and assertive, boldly proclaiming their “word of the Lord” in the marketplace; but today we learn that Samuel was different. In this story, he is marked by obedience and an openness to listen.

Young Samuel was in the temple, where the elderly Eli was priest. In the evening, while the lamp was still burning, Samuel hears a voice. The voice simply calls his name. “Here I am”, Samuel responds when he hears that voice. He is sure that it is Samuel,speaking to him—there is nobody else around. Three times, he hears “Samuel”; and three times, he responds “here I am” (vv.4,6,8).

Samuel had been thinking that it was Eli speaking to him; but it was not the priest, it was the voice of the Lord. The story conveys a sense of confusion and unknowing. This reflects something of the uncertainty that people of faith often have with regard to “hearing the voice of the Lord”.

Indeed, the fragility of living by faith without clear and obvious demonstration of he presence of God is signalled in the opening verse: “the word of the Lord was rare in those days; visions were not widespread” (v.1). The poor vision of the elderly priest, Eli (v.2), is a second signal of this uncertainty. The priest cannot see; the child hears but does not understand.

Paying attention to the voice of the Lord is a persistent refrain in Hebrew Scriptures. Indeed, the psalmist rejoices in the clarity of God’s voice: “the voice of the Lord is over the waters; the God of glory thunders, the Lord, over mighty waters; the voice of the Lord is powerful; the voice of the Lord is full of majesty” (Ps 29:3–4). Yet another psalmist recalls the time, in the wilderness, when the people of Israel “grumbled in their tents, and did not obey the voice of the Lord” (Ps 106:25). The people were not always faithful, even though the voice sounded with clarity. They needed reminders of that voice.

In the foundational saga of Israel, Moses is called by the voice of God while tending sheep on Mount Horeb (Exod 3:4). In obedience, he leads the people to freedom—and then informs the people, “if you will listen carefully to the voice of the Lord your God, and do what is right in his sight, and give heed to his commandments and keep all his statutes”, then God promises not to inflict them with disease (Exod 15:26). Later, when Moses has delivered to them “all the words of the Lord and all the ordinances”, the response of the people is an affirmative “all the words that the Lord has spoken we will do” (Exod 24:3).

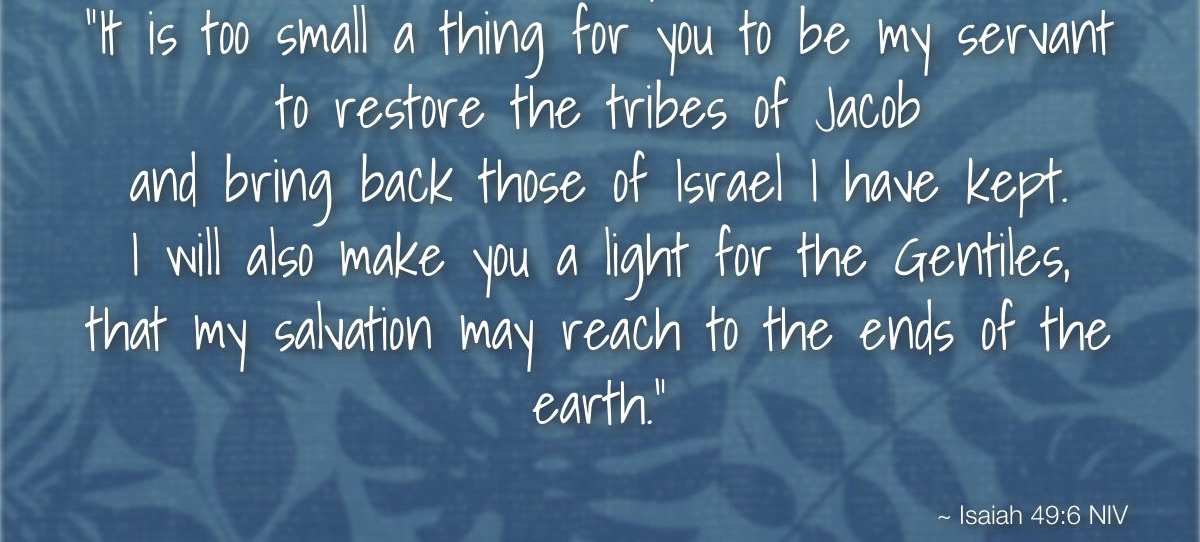

A number of the prophets indicate that they are impelled to declare “the word of the Lord” to a sinful people because they have heard, and are obedient to, “the voice of the Lord”. Isaiah hears the voice of the Lord calling him: “whom shall I send, and who will go for us?” (Isa 6:8). Isaiah is given words of woe to pronounce over the people (Isa 6:9–13); he warns the leaders of Israel, “listen, and hear my voice; pay attention, and hear my speech” (Isa 28:23).

His fellow-southerner, the shepherd Amos, opens his words with the bold declaration, “the Lord roars from Zion, and utters his voice from Jerusalem” (Amos 1:2), before he launches into his long series of oracles against the surrounding nations (Amos 1:3—2:3) and then against Judah and Israel (Amos 2:4–16).

The image of the Lord God as a roaring lion is used also by Joel, “the Lord roars from Zion, and utters his voice from Jerusalem, and the heavens and the earth shake” (Joel 3:16), while in another oracle he says, “the Lord utters his voice at the head of his army; how vast is his host!” (Joel 2:11).

Joel’s words of judgement penetrate to the heart of the evil of the people: the coming day will be “a day of darkness and gloom, a day of clouds and thick darkness!” (Joel 2:2), and so he calls the people to “return to [the Lord] with all your heart, with fasting, with weeping, and with mourning; rend your hearts and not your clothing” (Joel 2:12–13).

Micah also declares, “the voice of the Lord cries to the city (it is sound wisdom to fear your name)” (Mic 6:9) before he lambasts the people for their wickedness: “your wealthy are full of violence; your inhabitants speak lies, with tongues of deceit in their mouths” (Mic 6:12; the whole damning oracle is 6:9–16).

Called as a youth by “the word of the Lord” (Jer 1:4–8), Jeremiah hears the assurance, “I have put my words in your mouth” (Jer 1:9); the prophet later instructs the people, “amend your ways and your doings, and obey the voice of the Lord your God, and the Lord will change his mind about the disaster that he has pronounced against you” (Jer 26:13). Again, he tells them, “obey the voice of the Lord in what I say to you, and it shall go well with you, and your life shall be spared” (Jer 38:20). Eventually, the people affirm, “whether it is good or bad, we will obey the voice of the Lord our God to whom we are sending you, in order that it may go well with us when we obey the voice of the Lord our God” (Jer 42:6).

In the return from exile, both Haggai (Hag 1:12) and Zechariah (Zech 6:15) rejoice that Israel “obeyed the voice of the Lord their God”; but Daniel laments that his people “have not obeyed the voice of the Lord our God by following his laws, which he set before us by his servants the prophets; Israel has transgressed your law and turned aside, refusing to obey your voice” (Dan 9:10).

And yet, various prophets had hesitated when first hearing “the voice of the Lord”. The initial response of Moses is “who am I that I should go to Pharaoh, and bring the Israelites out of Egypt?” (Exod 3:11), followed by a series of further objections that he raises (Exod 3:13; 4:1; 4:10). Amos explains to the priest Amaziah how his call had surprised him: ““I am no prophet, nor a prophet’s son; but I am a herdsman, and a dresser of sycamore trees” (Amos 7:14).

Isaiah seeks to excuse himself from the prophetic task: “I am lost, for I am a man of unclean lips, and I live among a people of unclean lips” (Isa 6:5). Jeremiah objects, “truly I do not know how to speak, for I am only a boy” (Jer 1:6). A number of the prophets are, initially at least, reluctant spokespersons for the Lord God.

By contrast, in the story told in 1 Sam 3, after hearing his name spoken by the Lord for a third time, Samuel responds with a declaration of obedience: “speak, for your servant is listening” (v.10). This was just as the priest Eli had instructed him (v.9). Here, Samuel demonstrates careful listening, patience, openness to what he encounters, and complete obedience to that voice.

His response is similar to that of Mary when she is given startling news: “Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word” (Luke 1:38). Soon after that, she produced an amazing prophetic oracle, which we know as the Magnificat, declaring that God has “scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts … brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly … filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty” (Luke 1:51–53). Like Samuel, she proves to be an important prophetic voice.

This story from the early years of Samuel’s life is remembered and retold because it instructs those who hear it in later generations, to listen, and to obey. It is a reminder that being “guided by God” is not always clear and obvious. It is also a reminder of the need to respond with faith and openness; to be obedient. It is a story worth hearing, and pondering.