Elizabeth and I are leading a weekly study on The Prophets, because excerpts from these books appear in the Revised Common Lectionary as the Hebrew Scripture selection each week during the current church season (the long season of Pentecost). See

Our study series kicked off last week with two sessions of robust, engaged discussion (one on Thursday morning, the same session repeated on Thursday evening). I’ll be blogging material relating to this series and these readings 8n coming weeks.

The concept of a prophet was widely-known in the ancient world. Marvin Sweeney writes that “prophets were well known throughout the ancient Near Eastern world as figures who would serve as messengers or mouthpieces for the gods to communicate the divine will to their human audiences.”

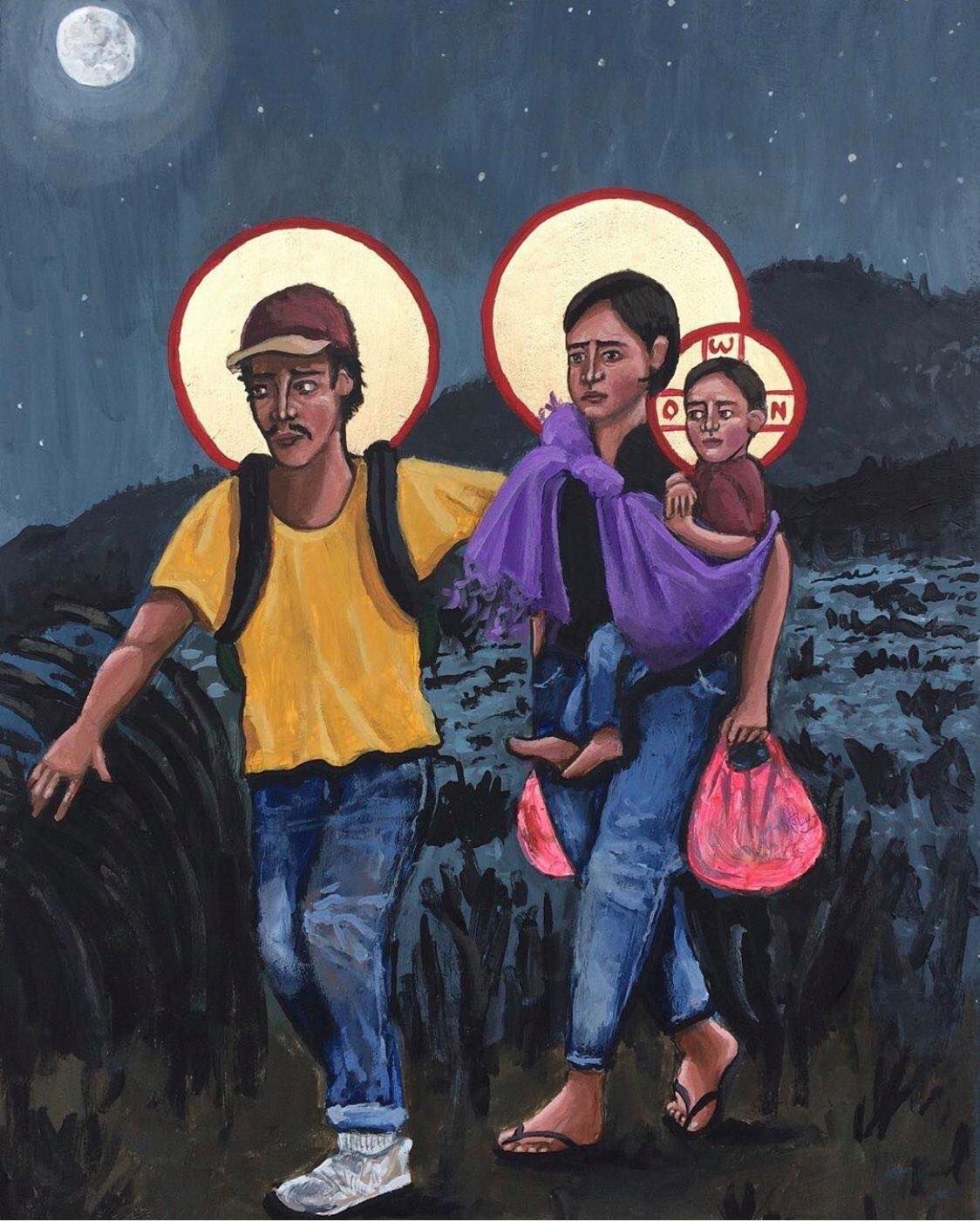

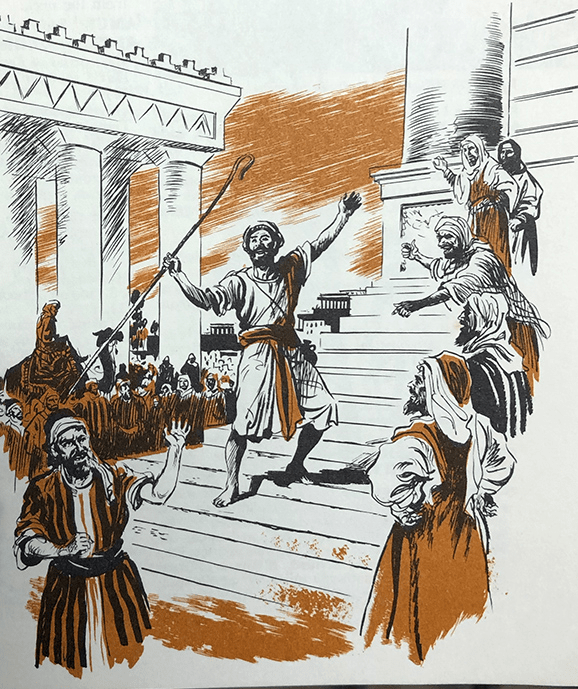

He notes, in particular: “Mesopotamian baru priests who read smoke patterns from sacrificial altars, examined the livers of sacrificial animals, read the movements of heavenly bodies … ecstatic muhhu prophets from the Mesopotamian city ofMari drew blood from themselves and engaged in trance possession as part of their preparation for oracular speech … the assinu prophets of Mari were well known for emulating feminine characteristics and dress as they prepared themselves to embody the goddess Ishtar of Arbela to speak on her behalf … Egyptian lector priests (see image) engaged in analysis of the worlds of nature and human beings in preparation for the well-crafted poetic compositions that gave expression to the will of the gods”. (“The Latter Prophets and prophecy”, pp.234–235 in The Cambridge Companion to the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, ed. Stephen B. Chapman and Marvin A. Sweeney, CUP, 2016)

The Hebrew Prophets typically claim that the word of the Lord came to me and pepper their speeches with the interjection, thus says the Lord. They often report visionary experiences which provide the divine authorisation for what they speak. Some are reported as having had ecstatic experiences where they travel out-of-body and, they say, see things from God’s perspective. A number of prophets engage in symbolic activities which underline the message delivered by their words. Woe to you is a standard introductory phrase, leading to condemnations on nations or people for their sinfulness.

Adherence to the covenant of the Lord lies at the root of all that the prophets say—they recall Israel to their distinctive task of being a holy people, dedicated to the Lord. “I have given you as a covenant to the people, a light to the nations”, Isaiah declares (Isa 42:6); “cursed be anyone who does not heed the words of this covenant”, cries Jeremiah (Jer 11:3); “I pledged myself and entered into a covenant with you, and you became mine”, Ezekiel declaims (Ezek 16:8).

Daniel prays, saying, “Ah, Lord, great and awesome God, keeping covenant and steadfast love with those who love you and keep your commandments, we have sinned and done wrong … turning aside from your commandments and ordinances” (Dan 9:4–5). Amos announces that Israel has “rejected the law of the Lord, and have not kept his statutes” (Amos 2:4); Hosea denounces the people, for “you have forgotten the law of your God” (Hos 4:6); Malachi berates the people in the name of God, for “ever since the days of your ancestors you have turned aside from my statutes and have not kept them” (Mal 3:7).

Similar declarations of the sinfulness of Israel, turning away from the covenant, recur in other prophetic books (Isa 30:9–11; Jer 2:20–22; Ezek 18:21–22, 24; Hos 8:1; Mal 2:4–17). So many of the oracles of judgement pronounced by the prophets are built on the assumption that the sinful behaviours being described indicate that Israel and Judah have turned from the covenant and are ignoring the commandments that God gave.

Ezekiel also notes that God says “I will establish with you an everlasting covenant” (Ezek 16:60), whilst Jeremiah says that God promises “I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah … I will put my law within them and I will write it on their hearts” (Jer 31:31–33). Hosea declares that God promises, “I will make for you a covenant … I will make you lie down in safety” (Hos 2:18).

The prophetic call for repentance is heard often (Isa 1:27; 45:22; 59:20; Jer 15:19; 18:11; 22:1–5; 35:15; 36:5–7; 44:4-5; Ezek 3:19; 14:6–8; 18:21–32; 33:8–9; Mal 4:4–6). This call is based on the premise that God will relent, and redeem those who turn from sinful practices. Sadly, Jeremiah notes that “the Lord persistently sent you all his servants the prophets”, but “you did not listen to me, says the Lord” (Jer 25:4-7). The work of a prophet is often thankless.

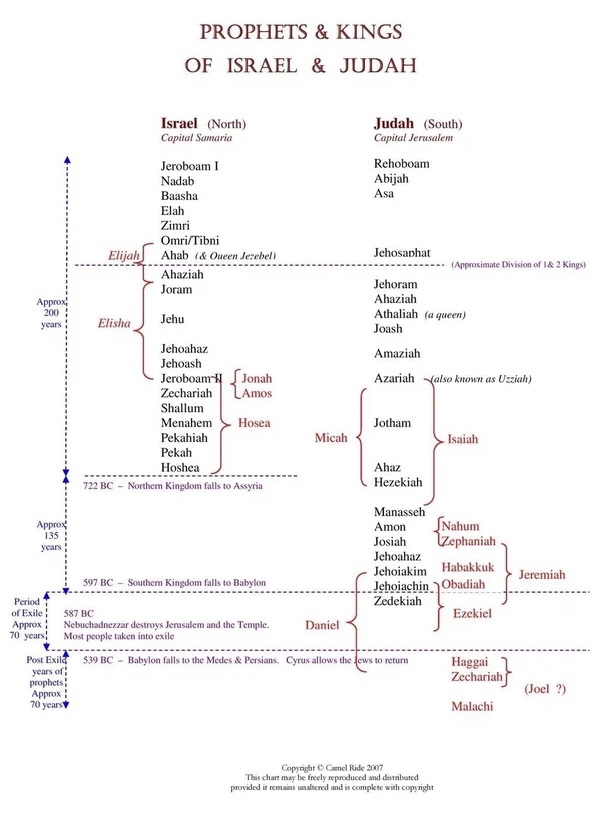

In the course, we are exploring each of the named prophets in our Bibles: the four Major Prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel) and the twelve Minor Prophets (Hosea—Joel—Amos—Obadiah—Jonah—Micah—Nahum—Habakkuk—Zephaniah—Haggai—Zechariah—Malachi); the latter ones are collected together in one scroll by Jews, who call this The Book of The Twelve. Some merit more detailed attention than others (because their works are longer), but all of them share a common concern to “set right” the people of Israel and Judah.

We have noted that there are others in scripture who are declared to be prophets, but who do not have a book dedicated to them. We’ll be paying some of them some attention as we work through the books. The first prophet mentioned in scripture is Miriam, the sister of Moses, who led the women of Israel in song, to celebrate victory over the Egyptians; the short Song of Miriam (Exod 15:20–21) was then attributed also to Moses, and placed at the head of a much longer song in his name (Exod 15:1–18).

Such musical leadership is recognised as an act of prophecy in the story of Saul: “you will meet a band of prophets coming down from the shrine with harp, tambourine, flute, and lyre playing in front of them; they will be in a prophetic frenzy” (1 Sam 10:5). Both males and females were able to serve as musicians who prophesied (1 Sam 18:6; 1 Chron 25:1–8).

Miriam is described as a prophet at Exodus 15:20 and again at Micah 6:4. She shares this designation with Deborah, who is introduced as a prophet “who was judging Israel” (Judg 4:4);. Deborah sits under a palm tree, the place for exercising judgement (Judg 4:5). However, the function of a “judge” was more akin to that of a military leader—a tribal elder who led military activities to protect their tribe from enemies and to establish justice within their group.

Deborah exercises such military leadership against Sisera, who led the army of King Jabin of Canaan. She recruits Barak to lead the fight (Judg 4:6–7); persuaded by her oracle, Barak insists that he will not fight unless Deborah goes out with him (Judg 4:8). When the Israelites gain victory over the Canaanite general (Judg 4:23–24), Deborah sings a song to celebrate her victory (Judg 5:1–31), maintaining the musical connection already noted in Miriam.

After the conquest and settlement of the land of Canaan, Samuel and Nathan figure significantly in the historical narratives about Israel. Samuel anoints Saul as the first king (and one interesting story about Saul ends with the question, is Saul also among the prophets? (1 Sam 19:18–24). Nathan, of course, is the prophet who promises David that “your house and your kingdom shall be made sure forever before me; your throne shall be established forever” (2 Sam 7:14). This is the oracle that assures the Davidic dynasty in Israel.

Nathan also is the one who confronts David about his adultery with Bathsheba, ending his famous parable of “the poor man [who] had nothing but one little ewe lamb” with the scathing denunciation: “you are the man” (2 Sam 12:1–7). Still later, Nathan tells the dying David of the plot by Adonijah to become king (1 Ki 1:11–14), leading to David’s final machinations which saw Solomon appointed as king (1 Ki 1:15–53) and the death of Adonijah (1 Ki 2:13–25).

Later in the time of the divided kingdoms, Elijah and Elisha serve as prophets to call the king to account for the sinfulness of the court, and of all the people. Elijah spectacularly defended Yahweh against the might of the prophets of Baal, who were being worshipped in Israel, even by King Ahab. The prophets of Baal were unable to call down fire for the sacrifice (1 Ki 18:26–29), but Elijah, building an altar and drenching it with water, was able to call down “the fire of the Lord [which] fell and consumed the burnt offering” (1 Ki 18:30–40).

Elisha raised the son of a Shunnamite woman (2 Ki 4:8–37), turned a poisoned pot of stew into an edible meal (2 Ki 4:38–41), and fed a hundred men with twenty loaves of barley (2 Kings 4:42–44); these stories evoke Jesus.

Elijah is taken up into heaven in a whirlwind (2 Ki 2), passing his mantle to Elisha. The last words of the prophet Malachi indicate that Elijah would return “before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes” (Mal 4:5–6); this prophecy plays an important role in New Testament texts. Just as it is not said that Enoch dies, but “walked with God, because God took him” (Gen 5:21–24), so this ascension of Elijah is believed to indicate that he did not die.

The final words uttered over Elisha were the same as those uttered over Elijah: “my father, my father! the chariots of Israel and its horsemen!” (2 Ki 13:14; cf. 2 Ki 2:12). His miraculous power lived on after his death; it is said that the body of a Moabite soldier killed in battle was thrown into his grave, and immediately “he came to life and stood on his feet” (2 Ki 13:20–21).

We might also include the woman of Endor as a prophet; despite the condemnation of divination (Deut 8:10–11), this woman provides Saul with guidance at the point where traditional means have failed. She consults with the ghosts; she sees “an old man is coming up, and he is wrapped in a robe” (1 Sam 28:14), and Saul recognises this as the ghost of Samuel. The deceased prophet thus directs the terrified king (1 Sam 28:15–19).

Later, we meet Huldah the wife of Shallum son of Tikva, son of Harhas, keeper of the wardrobe (2 Kings 22; 2 Chronicles 34). Both narratives tell of the reforms that took place under King Josiah, when a “Book of the Law” was discovered, and the king ordered that its prescriptions be followed. It is striking that Huldah, a female prophet, was consulted in relation to this book (not a male prophet). In a detailed oracle (2 Ki 22:16–20; 2 Chron 34:23–28), she speaks the word of the Lord to the king. Huldah validates the book that has been discovered.

Another female prophet is the wife of Isaiah, noted (without name) at Isa 8:3, who become the mother of one of Isaiah’s children; all of these children are given to be “signs and portents in Israel from the Lord of hosts” (Isa 8:18).

There were many more prophets active alongside Elijah and Elisha. Throughout the historical narratives, there are regular refences to “the prophets” (1 Sam 10:11–12; 1 Ki 18:4, 13, 20; 20:41; 22:6, 13; 2 Ki 23:2), “my servants the prophets” (2 Ki 9:7; 17:13, 23; 21:10; 24:2), a “band of prophets” (1 Sam 10:5, 10), a “company of prophets” (1 Sam 19:20; 1 Ki 20:35; 2 Ki 2:3, 5, 7, 15; 4:1, 38; 5:22; 6:1; 9:1), 2 Chron 18:5, 12), and “all the prophets” (1 Ki 19:1; 22:10–12; 2 Chron 18:9–11).

Indeed, later Jewish tradition refers to the forty-eight prophets and the seven prophetesses who prophesied on behalf of the Jewish people. The relevant section of the Talmud reads: “In fact, there were more prophets, as it is taught in a baraita*: Many prophets arose for the Jewish people, numbering double the number of Israelites who left Egypt. However, only a portion of the prophecies were recorded, because only prophecy that was needed for future generations was written down in the Bible for posterity, but that which was not needed, as it was not pertinent to later generations, was not written. Therefore, the fifty-five prophets recorded in the Bible, although not the only prophets of the Jewish people, were the only ones recorded, due to their eternal messages.” (Talmud, Megillah 14a) [* A Baraita is an ancient teaching that was not recorded in the Mishnah]

That would make the sum total of prophets a whopping 1,200,000 prophets! (This assumes the number of 600,000 “men on foot” as given at Exod 12:37—a gross exaggeration, by any account—-and also overlooks the complicating comment, “besides children”, and the complete omission of any reference to women!) We can at least say that there were more people undertaking prophetic activity than are named or designated in the scrolls of Hebrew scriptures. Whether each of them would meet the criteria that is set out for a true prophet (Deut 18:15-22), we will never know!

The seven female prophets are identified by later rabbis as Sarah, Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Hilda, and Esther. To read a brief contemporary Jewish discussion of the seven female prophets, see https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/4257802/jewish/The-7-Prophetesses-of-Judaism.htm

In the New Testament, the words of Joel that Peter cites on the Day of Pentecost indicate that the gifting of prophecy continues in this new era: “God declares that I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh, and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy … even upon my slaves, both men and women, in those days I will pour out my Spirit” (Acts 2:17–18).

So we find Anna described as a prophet (Luke 2:38), as is Zechariah (Luke 1:67) and his son, John the Baptist (Mark 6:15; Matt 11:9; 21:26; Luke 1:76; 7:26; 20:6), while Jesus himself is recognised as a prophet (Matt 14:5; 21:11, 46; Luke 7:16; 24:19; John 4:19; 6:14: 7:40–42; 9:17).

There were prophets active at the time of Jesus, as we see in his saying about welcoming a prophet (Matt 10:41). The movement that continued after the time of Jesus had prophets active such as the four daughters of Philip (Acts 21:9) and Agabus (Acts 21:10), as well as those gifted by the Spirit with the gift of prophecy (Rom 12:6; 1 Cor 12:10, 28–29; 13:2; 14:1–5, 22–25, 29, 37; Eph 2:20; 4:11; 1 Tim 4:14), although the activity here described as prophecy may well differ in significant ways from what is found throughout Hebrew Scripture.

*****

See also