We don’t have “signed autograph copies” of any of the Gospels in the NT, and we also don’t have any clear and explicit identification, in the texts of those Gospels, of who actually wrote them. I’ve already considered what we can reasonably deduce from within the contents of the Gospels; see https://johntsquires.com/2020/10/15/what-do-we-know-about-who-wrote-the-new-testament-gospels-1/

This post explores what was said about the Gospels by others.

1. Oral preferred to written. The first thing to note will seem rather curious to us. That is, the value placed on written accounts was far less than the value given to oral accounts, at least in the first few centuries of the history of the church.

A writer named Eusebius, who was Bishop of Caesarea from 314 until his death in 340, quotes an earlier bishop, Papias of Hierapolis (who lived 60-130 CE) as saying that he “did not suppose that the things from the books would aid me so much as the things from the living and continuous voice” (quoted in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 3.39.5).

Gnostic writers claimed that the sayings of Jesus were preserved in secret oral traditions (Ptolemaeus, Letter to Flora 3.8; Valentinus, Epistle to Rheginos 22, 25). These oral traditions were seen to validate their distinctive understandings of the faith. These writers came to be regarded as “heretical”; but a solidly “orthodox” theologian, Titus Flavius Clemens, a teacher in the Catechetical School of Alexandria in the later second century, wrote that he greatly valued the oral traditions because the early preachers all relied on the oral rather than the the written means of communicating (Clement, Stromata 5.26.5).

Likewise, Justin Martyr, a Samaritan who was trained in philosophy and became a Christian after encountering a very persuasive Syrian preacher, refers favourably to the oral traditions in his second century writings (Dialogue with Trypho 122.1, First Apology 61.4) even though he identifies and quotes from written sources.

So Eusebius of Caesarea writes that Matthew only wrote down his Gospel because he “compensated by his writing for the loss of his presence to those from whom he was sent”, and John had long preferred “unwritten preaching” but “finally resorted to writing also” (Ecclesiatical History 3.24.5). Written Gospels were originally seen as a second-best option.

2. The Gospel of Mark. Eusebius seeks to validate Mark’s Gospel by directly associating this written work with the verbal preaching of Peter. Mark, said Eusebius, simply wrote down “the things that Peter said”, and when Peter learnt of this, “he neither obstructed nor commended it” (Ecclesiastical History 6.14.5). In another place, Eusebius claimed that Peter had ratified the finished written product as acceptable “for study in the churches” (Ecclesiastical History 3.15.1).

The association of Mark’s Gospel with Peter’s preaching is subsequently claimed in the early third century by by Tertullian (Against Marcion 4.5) and Origen (quoted by Eusebius at Ecclesiastical History 6.14.5), and later in the fourth century by Jerome (in his Prologue to In Matt). There is no explicit link with the teachings of Peter in the text of Mark’s Gospel, however.

Likewise, the connection with Rome, where Peter is claimed to have died, is not found in any text until the fourth century Prologues (see further below).

3. The Gospel of Matthew. However, not everyone saw it this way. Augustine, in the early fifth century, considered that Mark’s Gospel was rougher than Matthew’s Gospel. Along with Origen and Jerome, Augustine considered that Matthew’s Gospel was written in Hebrew–and Mark, he wrote, “followed him closely and looks like his imitator and epitomiser” (Augustine, On the harmony of the Gospels 1.2.4).

Modern scholarly study of the Gospels has clearly demonstrated that Mark’s Gospel was earlier than Matthew’s, that Matthew used Mark as his source, and that it is quite unlikely that Matthew wrote in Hebrew, given that his Greek follows that of Mark so often! So we can discount Augustine’s claim—as almost all biblical scholars do today.

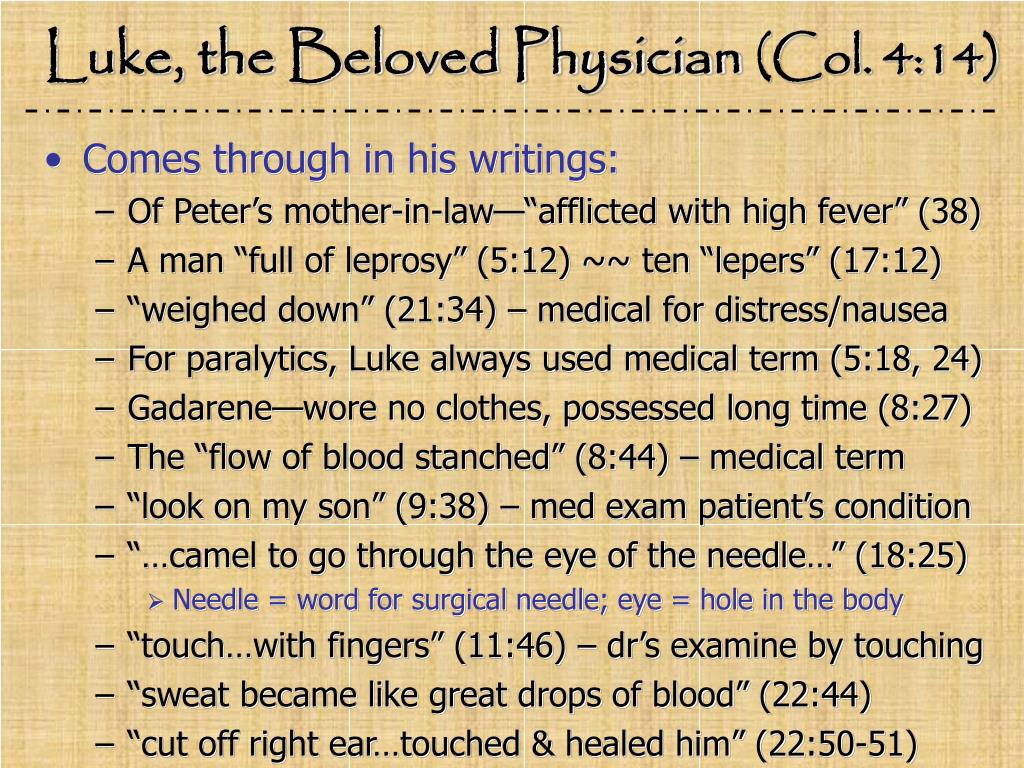

4. The Gospel of Luke. Eusebius argues that the limited value and significance of oral traditions is conveyed in the opening verses of Luke’s Gospel (Ecclesiastical History 3.24.15). Luke, he infers, had found the written narratives which he consulted to be somewhat unreliable, so he conferred with “eyewitnesses” to gain better insight from the oral traditions. (Eusebius identifies those “eyewitnesses” as Paul and other Apostles).

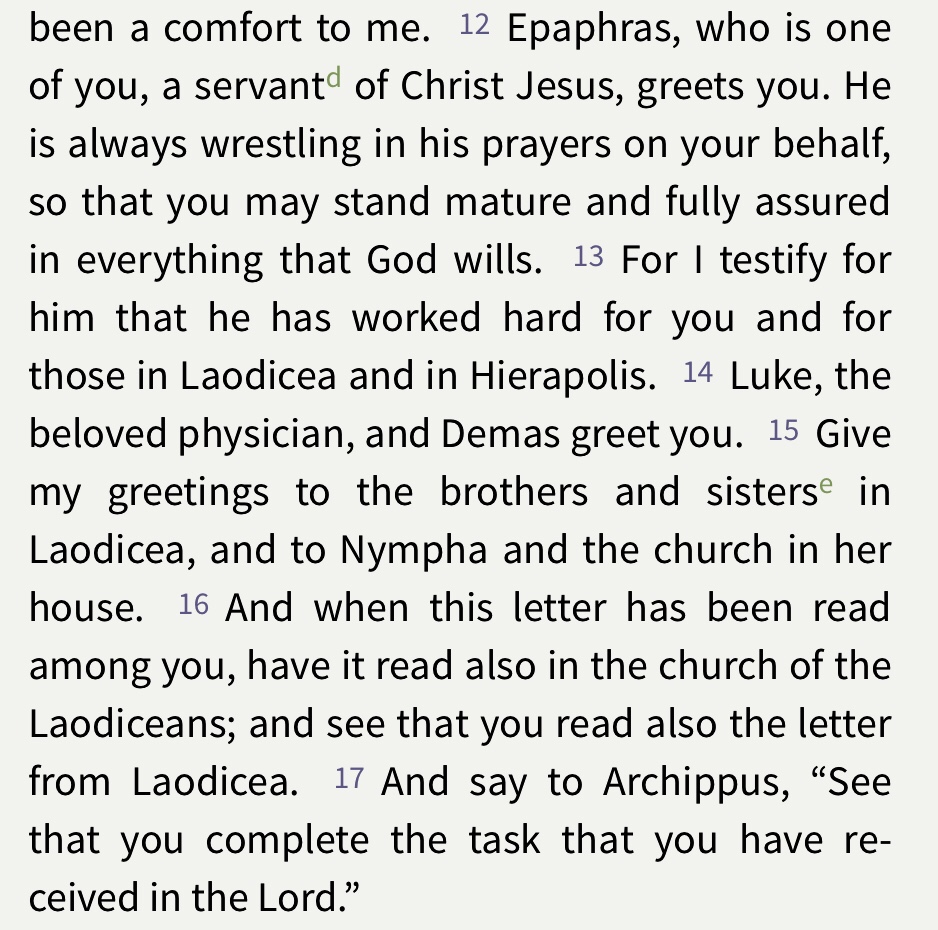

In the early discussion of Luke’s Gospel, the author is described simply as the companion of Paul: we find this in Origen (quoted in Ecclesiastical History 6.25) and Jerome (On Famous Men 7). This is also the description of the author found in the Muratorian Canon, a list of books which most likely dates from the fourth century, as well as the Anti-Marcionite Prologue to Luke, and the Monarchian Prologue to Luke, from the same period.

Luke is first claimed as a doctor in the Anti-Marcionite Prologue to Luke, which simply states that Luke “was born in Antioch, by profession was a physician … he died at the age of 84 years”. This is also claimed in the Monarchian Prologue to Luke. These are fourth century documents; this claim about Luke had not been made in any extant work before this time.

Around the same time, Jerome affirms that the author of Luke’s Gospel was indeed a doctor who offered “medicine for the sick soul” (Jerome, Epistle 53.9). Whilst this aspect of Luke’s identity appears not ever to have been noted in the second or third centuries, it was apparently well-known in the fourth century.

Also in the fourth century, Epiphanius of Salamis placed Luke amongst the seventy people who were sent out on mission (who are described only in Luke’s account, Luke 10:1-20) (Epiphanius, Panarion 51.11), whilst John Chrysostom, the famous preacher of Antioch and later Bishop of Constantinople, identified him as “the brother who is famous among all the churches for his proclaiming the good news”, who is mentioned by Paul in 2 Cor 8:18 (Chrysostom, Homily 18 on Second Corinthians). In neither case it is claimed that Luke had medical expertise.

This leads to a striking observation: the further away in time we get from when the Gospels were actually written, the more that we seem to know about who wrote each of them! Or, to put it the other way, close to the time of writing we know very little about the authors; some centuries later, after discussion of these texts by Christian writers, we seem to know much more about the authors!! Traditions grew and expanded over time, under the impetus of “needing to know” more about the authors of the Gospels.

5. The Gospel of John. The differences of context between the first three Gospels and John’s Gospel did not escape the notice of early writers. Clement of Alexandria states that “John, noticing that the physical things had been set forth in the Gospels … wrote a spiritual Gospel” (quoted by Eusebius at Ecclesiastical History 6.14.5).

The fourth-century Muratorian Canon claims that John wrote his Gospel in response to the urgings of “his fellow disciples and bishops”, especially Andrew. Jerome has a similar claim, that John wrote “when asked by the bishops of Asia” (Jerome, On Famous Men 9).

It needs to be noted that Jerome was reading back his fourth century context into the first century, assuming that there were bishops in all the churches. Of course, that is what is claimed by later church tradition; but historical reality was probably that bishops did not emerge until some time in the second century, and were not universally in place until later in the third century. So this is a confected story, surely.

Jerome says more about the author of John’s Gospel, who, “reclining on the breast of the Lord, drank the purest streams of teachings”. Even though he wrote “in haste”, nevertheless “he was saturated with revelation and burst forth into that heaven-sent prologue” (Jerome, prologue to John In Matt.)

Then, in the Monarchian Prologue to John, John is portrayed as an incorruptible virgin, writing to reveal deep mysteries, which he can do because he is not merely one of the Apostles; he is “one of the disciples of God”, a totally inspired writer.

In like manner, in these prologues, Luke is praised as “serving God without blame … never having either a wife or children”, whilst Mark, a Jew who was “a Levite according to the flesh”, was said to have “amputated his thumb after he embraced the faith, that he might be accounted unfit for the priesthood”, and thus able to devote himself to his writing task. And thus arose the story that Mark was colobodactylus (“stump-fingered”).

But now, we are such a long way from any rigorous historical investigation into the actual identity of the writers of the Gospel, and deep into the developing myths and traditions of the church!

*****

For interest sake, here are the three anti-Marcionite Prologues (the prologue to Matthew is not extant). They come from later in the fourth century and contain far more “information” about the evangelists than is evident in any earlier literature. How reliable, really, is all of this additional “information”?

Mark made his assertion, who was also named stubby-fingers, on account that he had in comparison to the length of the rest of his body shorter fingers. He was a disciple and interpreter of Peter, whom he followed just as he heard him report. When he was requested at Rome by the brethren, he briefly wrote this gospel in parts of Italy. When Peter heard this, he approved and affirmed it by his own authority for the reading of the church. Truly, after the departure of Peter, this gospel which he himself put together having been taken up, he went away into Egypt and, ordained as the first bishop of Alexandria, announcing Christ, he constituted a church there. It was of such teaching and continence of life that it compels all followers of Christ to imitate its example.

The holy Luke is an Antiochene, Syrian by race, physician by trade. As his writings indicate, of the Greek speech he was not ignorant. He was a disciple of the apostles, and afterward followed Paul until his confession, serving the Lord undistractedly, for he neither had any wife nor procreated sons. [A man] of eighty–four years, he slept in Thebes, the metropolis of Boeotia, full of the holy spirit. He, when the gospels were already written down, that according to Matthew in Judea, but that according to Mark in Italy, instigated by the holy spirit, in parts of Achaea wrote down this gospel, he who was taught not only by the apostle, who was not with the Lord in the flesh, but also by the other apostles, who were with the Lord, even making clear this very thing himself in the preface, that the others were written down before his, and that it was necessary that he accurately expound for the gentile faithful the entire economy in his narrative, lest they, detained by Jewish fables, be held by a sole desire for the law, or lest, seduced by heretical fables and stupid instigations, they slip away from the truth. It being necessary, then, immediately in the beginning we receive report of the nativity of John, who is the beginning of the gospel, who was the forerunner of our Lord Jesus Christ, and a partaker in the perfecting of the people, and also in the induction of baptism, and a partaker of his passion and of the fellowship of the spirit. Zechariah the prophet, one of the twelve, made mention of this economy. And indeed afterward this same Luke wrote the Acts of the Apostles. And later John the apostle from the twelve first wrote down the apocalypse on the isle of Pathmos, then the gospel in Asia.

John the apostle, whom the Lord Jesus loved very much, last of all wrote this gospel, the bishops of Asia having entreated him, against Cerinthus and other heretics, and especially standing against the dogma of the Ebionites there who asserted by the depravity of their stupidity, for thus they have the appellation Ebionites, that Christ, before he was born from Mary, neither existed nor was born before the ages from God the father. Whence also he was compelled to tell of his divine nativity from the father. But they also bear another cause for his writing the gospel, because, when he had collected the volumes from the gospel of Matthew, of Mark, and of Luke, he indeed approved the text of the history and affirmed that they had said true things, but that they had woven the history of only one year, in which he also suffered after the imprisonment of John. The year, then, having been omitted in which the acts of the tribes were expounded, he narrated the events of the time prior, before John was shut up in prison, just as it can be made manifest to those who diligently read the four volumes of the gospels. This gospel, then, after the apocalypse was written was made manifest and given to the churches in Asia by John, as yet constituted in the body, as the Hieropolitan, Papias by name, disciple of John and dear [to him], transmitted in his Exoteric, that is, the outside five books. He wrote down this gospel while John dictated. Truly Marcion the heretic, when he had been disapproved by him because he supposed contrary things, was thrown out by John. He in truth carried writings or epistles sent to him from the brothers who were in Pontus, faithful in Christ Jesus our Lord.

And here are the four Monarchian Prologues from a similar timeframe, with equally loquacious and imaginative expositions about each of the evangelists.

Matthew, from Judea, just as he is placed first in order, so wrote the gospel first in Judea. His calling to God was from publican activities. He presumed in the genealogy of Christ the beginnings of two things, the first of which was circumcision in the flesh, the other of which was election according to the heart, and by both of which Christ was in the fathers. And, the number having thus been put down as three fourteens, he shows by extending the beginning from the faith of the believer unto the time of election, and directing it from the election to the day of the deportation, and defining it from the deportation up to Christ that the generation of the advent of the Lord had been reached, so that, in making satisfaction both in number and in time, and in showing itself for what it was, and in demonstrating that the work of God in itself was still in these whose race he established, the time, order, number, economy, or reason of all of these matters might not deny the testimony, which is necessary for faith, of Christ, who was working from the beginning. God is Christ, who was made from a woman, who was made under the law, who was born from a virgin, who suffered in the flesh, who fixed all things on the cross so that, triumphing over them for eternity, rising in the body, he might restore both the name of the father to the son in the fathers and the name of the son to the father in the sons, without beginning, without end, showing that he is one with the father, because he is one. In this gospel it is useful for those desiring God to know the first things, the medial things, and the perfect things, so that, reading of the calling of the apostle and the work of the gospel and the choosing of God, born into the universe in the flesh, they might understand and recognize it in him, in whom they have been apprehended and seek to apprehend. It was certainly possible in this study of the subject matter for us to both convey the fidelity of what was done and not be silent that the economy of God at work must be diligently understood by those seeking to do so.

This is John the evangelist, one from the twelve disciples of God, who was elected by God to be a virgin, whom God called away from marriage though he was wishing to marry, for whom double testimony of his virginity is given in the gospel both in that he was said to be beloved by God above others and in that God, going to the cross, commended his own mother to him, so that a virgin might serve a virgin. Furthermore, manifesting in the gospel that he himself was starting up the work of the incorruptible word, he alone testifies that the word was made flesh and that light was not comprehended by darkness, placing the first sign which God did in a wedding so as to demonstrate to those reading, by showing what he himself was, that where the Lord is invited the wine of weddings ought to cease and also that all things which have been set up by Christ, now that the old things have been changed, might appear new. Concerning this the reason for [composing] the gospel to those seeking shows the separate things which were done or said in a mystery. Moreover, he wrote this gospel in Asia, after he had written the apocalypse on the island of Patmos, so that, to whom the incorruptible beginning was attributed in the beginning of the canon, in Genesis, to him also the incorruptible end through a virgin in the Apocalypse might be attributed, since Christ says: I am the alpha and the omega. And this is the John who, knowing that the day of his departure had come upon him, his disciples having been called together in Ephesus, producing Christ through the many signs that were accomplished, descending into the place dug out for his sepulture, after a prayer was made, was laid with his fathers, as much a stranger to the pain of death as he was found alien to the corruption of the flesh. And, if he is said to have written the gospel after all [the others], he is however placed after Matthew in the disposition of the canon as it is ordered, since in the Lord those things that are newest are not as if last and rejected for their number, but rather have been perfected by the work of fulness; and this was due to a virgin. Neither the disposition of the writings by time nor the order of the books, however, are exposited by us in the details, so that, when the desire to know has been settled, both the fruit of labor and the doctrine of teaching for God might be reserved for those who seek.

Luke, Syrian by nationality, an Antiochene, physician by art, disciple of the apostles, later followed Paul up until his confession, serving God without fault. For, never having either a wife or sons, he died in Bithynia at seventy-four years of age, full of the holy spirit. When the gospels through Matthew in Judea, through Mark, however, in Italy, had already been written, he wrote this gospel at the instigation of the holy spirit in the regions of Achaea, he himself also signifying in the beginning that others had been written beforehand. For whom, beyond those things which the order of the gospel disposition implores, there was that necessity of labor especially, that he should labor first for the Greek faithful lest, after all the perfection of God come in the flesh was made manifest, they either be intent on Jewish fables and held by a sole desire for the law or slip away from the truth, seduced by heretical fables and stupid instigations; furthermore, that in the beginning of the gospel, after the nativity of John had been taken up, he might indicate to whom it was that he wrote his gospel and by what [purpose] he elected to write it, contending that those things that had been started by others were completed by him. To him, therefore, was permitted the power [to record events] after the baptism of the son of God, from the perfection of the generation fulfilled and to be repeated in Christ, from the beginning of his human nativity, so that he might demonstrate to those who thoroughly seek, insofar as he had apprehended it, that, by the admitted introduction of a generation which runs back through a son of Nathan to God, the indivisible God who preaches his Christ among men made the work of the perfect man return into himself through the son, he who through David the father was preparing a way in Christ for those who were coming. To this not immeritorious Luke was given the power in his ministry of writing also the acts of the apostles so that, when God had been filled up in God and the son of treachery extinguished, and prayers made by the apostles, the number of election might be completed by the lot of the Lord, and that thus Paul, whom the Lord elected despite long kicking against the pricks, might give a consummation to the acts of the apostles. Though it were also useful for those reading and thoroughly seeking God that this be explained by us in the details, nevertheless, knowing that it is fit for the working farmer to eat from his own fruits, we have avoided public curiosity, lest we should be seen as, not so much demonstrating God to those who are willing, but rather having given it to those who loathe him.

Mark, the evangelist of God and in baptism the son of the blessed apostle Peter and also his disciple in the divine word, performing the priesthood in Israel, a Levite according to the flesh, but converted to the faith of Christ, wrote the gospel in Italy, showing in it what he owed to his own race and what to Christ. For, setting up the start of the beginning with the voice of the prophetic exclamation, he showed the order of his Levitical election so that he, preaching by the voice of the announcing messenger that John the son of Zechariah was the predestinated one, might show at the start of the preaching of the gospel not only that the word made flesh had been sent out but also that the body of the Lord had been animated in all things through the word of the divine voice, so that he who reads these things might realize not to be ignorant to whom he owes the start of the flesh in the Lord and the tabernacle of the coming God, and also that he might find in himself the word of the voice which had been lost in the consonants. Furthermore, both going on with the work of the perfect gospel and starting that God preached from the baptism of the Lord, he did not labor to tell of the nativity of the flesh, which he had conquered* in prior portions, but rather right at first he offered the expulsion into the desert, the fasting for the number, the temptation by the devil, the gathering of the beasts, and the ministry by angels, so that, in setting us up to understand by sketching out the details in brief, he might not diminish the authority of what was already done, nor deny the work to be perfected in fulness. Furthermore, he is said to have amputated his thumb after faith so that he might be held to be unfit for the priesthood. But the predestinated election held such power, consenting to his faith, that he did not in his work of the word lose what he had previously merited by his race, for he was the bishop of Alexandria, whose work it was to know in detail and to apply the things said in the gospel on his own, and not to be ignorant of the discipline of the law for himself, and to understand the divine nature of the Lord in the flesh. These things we also wish to be sought first, and, when they have been sought, not to be ignored having the reward of the exhortation, since he who plants and he who waters are one; he who yields the increase, however, is God.