A Sermon –preached by James Ellis for Advent 4A – Sunday 18 December 2022 – at Tuggeranong Uniting Church, on the occasion of his commissioning into the specified ministry of Lay Preacher within the Uniting Church in Australia

Readings: Matthew 1: 18-25 (with reference to Isaiah 7: 10-16).

Christmas is coming – or so we have been saying over the past four Sundays! Our lighting of the fourth candle on our advent wreath this morning – the candle of ‘love’ – marks the final days of advent. Christmas is ever closer, but it is not quite here yet.

Some liturgical fusspots can get in a flap about crossing the Christmas threshold “too early” – that is before Christmas Eve, and I admit – not to great surprise I am sure – that I am usually one of these fusspots – especially when it comes to Lent and Advent.

Well, it seems that the lectionary is not so fussy and frequently prepares us for what lies ahead with a spoiler. That is the case today where our Gospel reading: Matthew’s account of the birth of Jesus. This account, a week before Christmas for us this year, invites us to start pondering the great marvel that is Jesus coming among us in anticipation of Christmas.

Matthew’s story of Jesus’ birth is very much from the point of view of Joseph. This is quite unique. We usually focus on Mary – and rightly so! We don’t know much about Joseph. We can guess, make assumptions, follow the ‘tradition’ attributed to him – but we simply don’t know. He seems to disappear from the story following the birth. Even when later in Matthew’s Gospel, when Jesus is lost in Jerusalem as a boy, it is his mother Mary who finds (and scolds) him, not Joseph. At the Cross, Mary is there, but Joseph is not. Perhaps, as tradition assumes, Mary is a widow and Joseph has died.

So, where Luke is very much focussed on Mary’s story and journey, Matthew gives us some insight into Joseph and the situation he found himself in. In this we see the human side of this story…

Joseph is betrothed (NRSV – engaged) to Mary. At the time, this was not like how we view engagement today where it can be called off rather informally. But contracted to marry and considered bound by the laws of marriage, just not living together yet. Scholar Brendan Byrne makes this point in his commentary on this passage when he details the practice of the time to be betrothed young and not live together until much later. The “before they lived together” in verse 18 is to emphasise they had not had any kind of relations together.

It is during this waiting that Joseph becomes aware that Mary is pregnant. We can imagine the dilemma Joseph found himself in – the ambiguity; the lack of certainty; the confusion. He needs reassurance, but also society requires from him a posture of honour and respect. The initial assumption here – for Joseph and anyone who knew – is that Mary has committed adultery. An act which could get her stoned to death under the Deuteronomic laws.

Joseph, as the man ‘wronged’, would be expected at a minimum to divorce (dismiss) her in public and have her attract the shame and humiliation of many other women who have been in a similar situation. We read however that Joseph was a righteous man – and unwilling to expose Mary to such public disgrace (v19). So, he plans to dismiss her ‘quietly’. Still somewhat harsh in our context, but compassionate in his. This reveals to us something of Joseph’s character that he doesn’t want to bring Mary public shame but instead wants to protect her. He cares about her. He loves her.

This is attitude and plan before the truth is revealed to him in a dream – where an angel tells him that Mary is in fact pregnant by the Holy Spirit and not because she has been up to no good. Compared to other Angel appearances, Joseph listens and acts. He doesn’t argue or dismiss or come up with excuses. It is almost as though this was what he wanted to hear or needed to hear.

While we could argue around the who, where, how of a virgin birth, that isn’t the point here today. The Focus here is instead to consider the mysterious and the miraculous as the way that God deals with humanity. Whether it is Abraham and Sarah, Moses (particularly his survival as an infant), Samson, Samuel, Elizabeth and Zechariah … this is the way God deals with the humanly impossible and brings in the new – with impossible births. This is powerful, very powerful, and is the story that speaks through this story.

Matthew understands this of this story also and we see this by the way he links this event with those contained in Isaiah, also read this morning. “Look, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel”, which means God with us (v23). Isaiah 7 speaks of the birth of a child, who will be named “Emmanuel”. His birth is a “sign” of God’s promise to deliver and bless King Ahaz and the Judean people with abundance, but also of devastating judgment if the sign is refused. When the son born of the “virgin,” or young woman, is rejected, he becomes a sign of judgment rather than deliverance. Matthew uses the citation of Isaiah 7:14 to indicate that Jesus’ person and mission compel people to make choices, resulting in both redemption and judgment.

The use of “God with us” in Matthew 1:23 and 28:20 thus frames the whole Gospel, which serves as a comprehensive narrative that defines what it means for Jesus to be God with us. The culmination of Jesus’ mission in his death and resurrection means that God’s work of redemption has reached its climactic moment, when Israel is gathered and restored, the mission to the nations has begun, and the whole creation—heaven and earth—will be restored and renewed as God’s dwelling place.

What role might disciples—all of us—play in the continuing realization of this story?

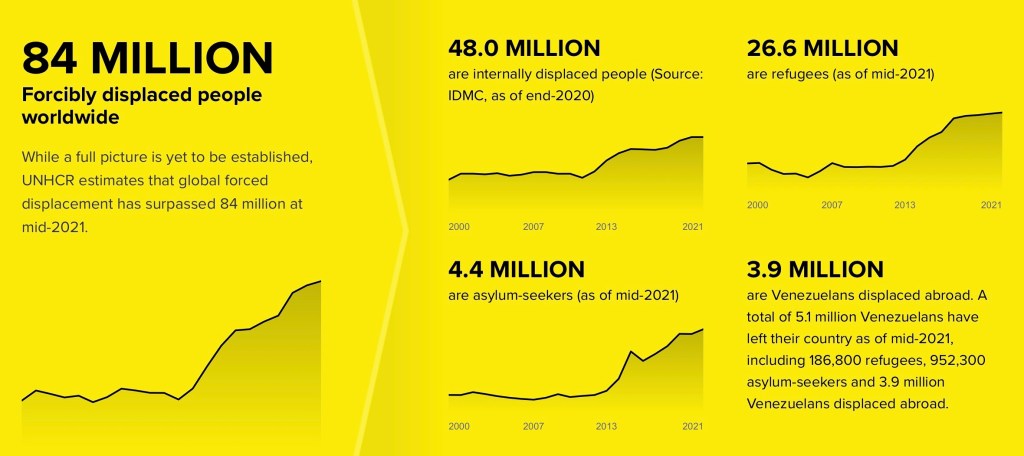

How is this story still our story in a world ever more filled with greed, exploitation, violence, and death?

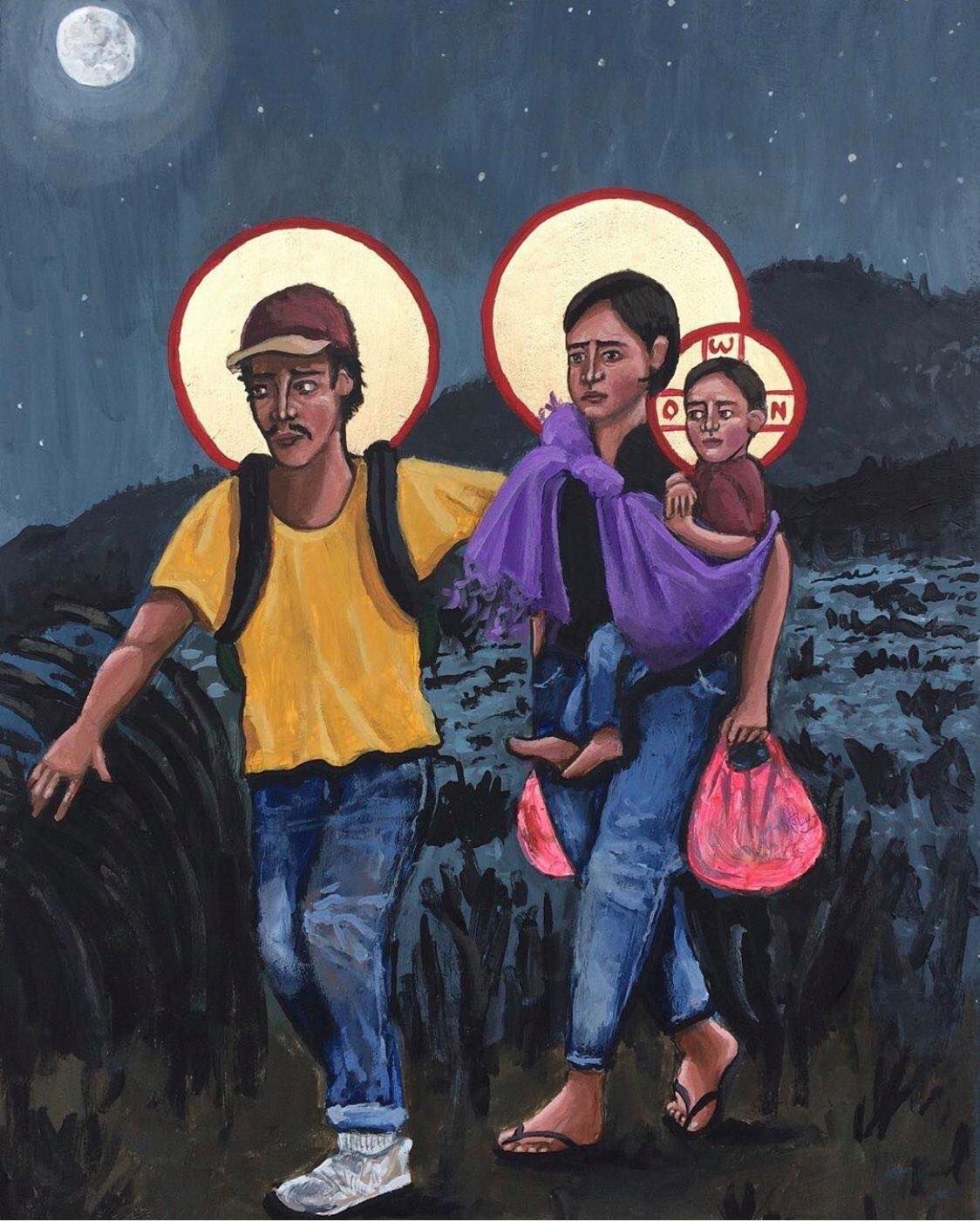

The birth narrative ends with an act of love and commitment from Joseph – where it is he that names Jesus. They become a family, a family of choice. Because of this choice of Joseph’s, Jesus becomes part of the line of David. This family is far from the typical family at the time, but perhaps speaks well into our context.

Rev Dr Jo Inkpin, in her lectionary reflections for the latest issue of Insights, says this about the example of Joseph and the Holy family: “It is an extraordinary family, and as such should give courage to all other families that do not fit neatly into what society says they should. For those who do live within typical expectations this family may also give strength to acknowledge hidden differences and to support those who face other hurts and condemnations. Without the courage of both Joseph and Mary in choosing to step outside conventional boundaries, exercising compassion and common sense, the Christian story could not have begun”.

I have often heard it said: you don’t know true love until you become a parent. And while the love I experienced when my daughter was born truly made me experience love I never had before – to say I didn’t really know love until then feels … shallow? diminutive?

It seems to me, then, that there are all kinds of love we don’t know until we know it. The love of true, deep friendship. The love of finding a vocation that fills you with purpose. The love of a place that becomes home, perhaps unexpectedly. The love of children birthed or adopted, fostered or through partnership. The love of a community that is a family – like here at Tuggeranong.

Advent is a journey of God’s unfolding love for us, with us, and before us; it is a time of living in the “here” of a world where Christ came as an infant 2,000 years ago and a time of “not yet” as we live in the midst of sin and sorrow and despair. Advent challenges us to live in this paradox without resolving it.

And Advent is a time where we are pushed to trust that the love God has for us is going to carry us through – perhaps through unknown paths, or along a winding highway, and almost definitely not where we thought we would go. But the love of God will never, never fade or tire. For God’s love for us is greater than the love parents have for their children, and greater than the love friends have for each other, and greater than the love Joseph showed to Mary and Jesus.

May we journey together in love this last week of Advent.

The Lord be with you.

*****

Source material: By the Well podcast and Working Preacher podcast, Brendan Byrne, Lifting the Burden: Reading Matthew’s Gospel in the Church Today (Liturgical Press, 2004)