Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light. (Matt 11:28-30)

The book of origins, the first of four accounts of Jesus in the New Testament (known to us as the Gospel according to Matthew), locates Jesus firmly within his historical context, as a teacher and prophet within Israel. He is the one who has come to renew the covenant, to restore Israel, to instruct them in the ways of righteous-justice. He is the one who brings the Law to fulfilment and establishes the way into the kingdom.

This book has a high view of Jesus within that Jewish context. It positions Jesus as the most authoritative teacher in his community, the one who guides, directs, and inspires those who listen to him.

It is to the words of Jesus that believers are to look for guidance in their lives (7:24–27). In this Gospel, Jesus is the one and only teacher (23:8), the one and only instructor (23:10). Whilst “heaven and earth will pass away”, the words spoken by Jesus will endure (24:35). The last words of Jesus reported in this book are the instructions from Jesus, to his disciples, to go to the nations, “teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you” (28:20). His teachings stand supreme.

In the lectionary for this coming Sunday, we find a striking passage from Matthew’s Gospel (11:25–30) which depends this understanding of Jesus the Teacher. In this passage, Jesus offers a prayer to God in which he lays claim to this distinct, even unique, place.

The first part of this passage (11:25-27) is often nicknamed “the Johannine Thunderbolt from a Synoptic Sky”, because it seems so out of place in this Gospel; the language used (“Father” and “Son”, amongst other things) invites comparison with the Fourth Gospel, as does the insistence on Jesus as the one who “knows the will of the Father” and thus reveals “the gracious will” of the Father (11:26-27). How these verses found there way into this particular Gospel is an intriguing question. (If you have a compelling answer to this question, I would love to hear it!)

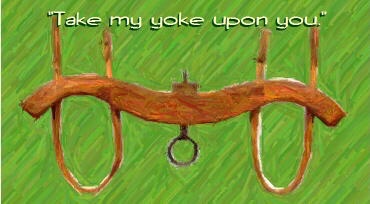

As this prayer continues (11:28-30), Jesus is depicted as laying claim to be the authoritative teacher; his words claim an absolute authority to interpret the Law, which is here portrayed as “the yoke”, a term for the Law which is found in rabbinic writings (Mishnah, Aboth 3:5, Berakoth 2:5; see also 2 Enoch 34:1 and 2 Baruch 41:3).

Jesus here is portrayed as claiming this high authority for himself; his yoke provides a sure understanding of the Law. His language is filled with scriptural words; he speaks in a way that is strongly evocative of certain passages in Sirach concerning Wisdom (Sirach 6:18–33; 24:19–22; 51:23–28). In this book (dating from around 200-250 years before the time of Jesus), Wisdom commands attention (“draw near to me”, “come to me”), offers instruction, commands submission to the yoke of her teaching, and offers rest.

A hymn on the values of Wisdom concludes that book, with the invitation to “acquire wisdom for yourself … put your neck under her yoke and let your souls receive instruction” (Sir 51:25-26). Earlier in the book, this invitation to learn from Wisdom had been issued by Wisdom herself: “come to me, you who desire me, and eat your fill of my fruits” (Sir 24:19).

And in the opening chapters of this book, an extended poem in praise of wisdom includes the invitation to “come to her like one who plots and sows … put your feet into her fetter and your neck into her collar, bend your shoulders and carry her, and do not fret under her bonds … come to her with all your soul … search out and seek … when you get hold of her, do not let her go, for at last you will find the rest she gives, and you will be changed into joy for you” (Sir 6:19, 24-28).

The poem continues, “then her fetters will become for you a strong defence and her collar a glorious robe; her yoke is a golden ornament, and her bonds a purple cord; you will wear her like a glorious robe and put her on like a splendid crown” (Sir 6:29-31).

So many of these phrases resonate in the words attributed to Jesus in the book of origins (Matt 11:28-30). As he speaks, he claims the authority of Wisdom. His words provide insight, guidance, direction, as do the words of Wisdom in earlier Jewish traditions. Indeed, just a few verses earlier, the voice of Wisdom has been invoked by Jesus as he reflects on the criticisms he has received, as “a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners” (11:19). The proof of the pudding is in the eating—“Wisdom is vindicated by her deeds”, is what Jesus responds.

Wisdom appears in the book of Proverbs, where she is portrayed as a teacher of “good advice and sound wisdom” who offers insight and strength (Prov 8:14), leading people along “the way of righteousness, the paths of justice” (8:20). She is also portrayed as the one who worked beside God to bring the created world into being (8:22-31).

Wisdom then appears in later Jewish literature, including Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), always as the teacher, instructing people in God’s ways, instructing and guiding people of faith through their journeys in life.

We have noted in earlier blogs that this Gospel, the book of origins, came into being in a community which found itself in competition with regard to other streams of Judaism. (See the blog posts listed below.) This Gospel, it would seem, seeks to validate the interpretation of scripture promoted by the followers of Jesus over and above other understandings and interpretations of the Law.

Who better to call upon for such validating support than the master exegete, the authoritative teacher, Jesus, the one to whom “all things have been revealed by the heavenly Father”, the one who speaks with the voice of Wisdom herself?

This blog draws on material in MESSIAH, MOUNTAINS, AND MISSION: an exploration of the Gospel for Year A, by Elizabeth Raine and John Squires (self-published 2012)

See also

https://johntsquires.com/2019/11/28/leaving-luke-meeting-matthew/

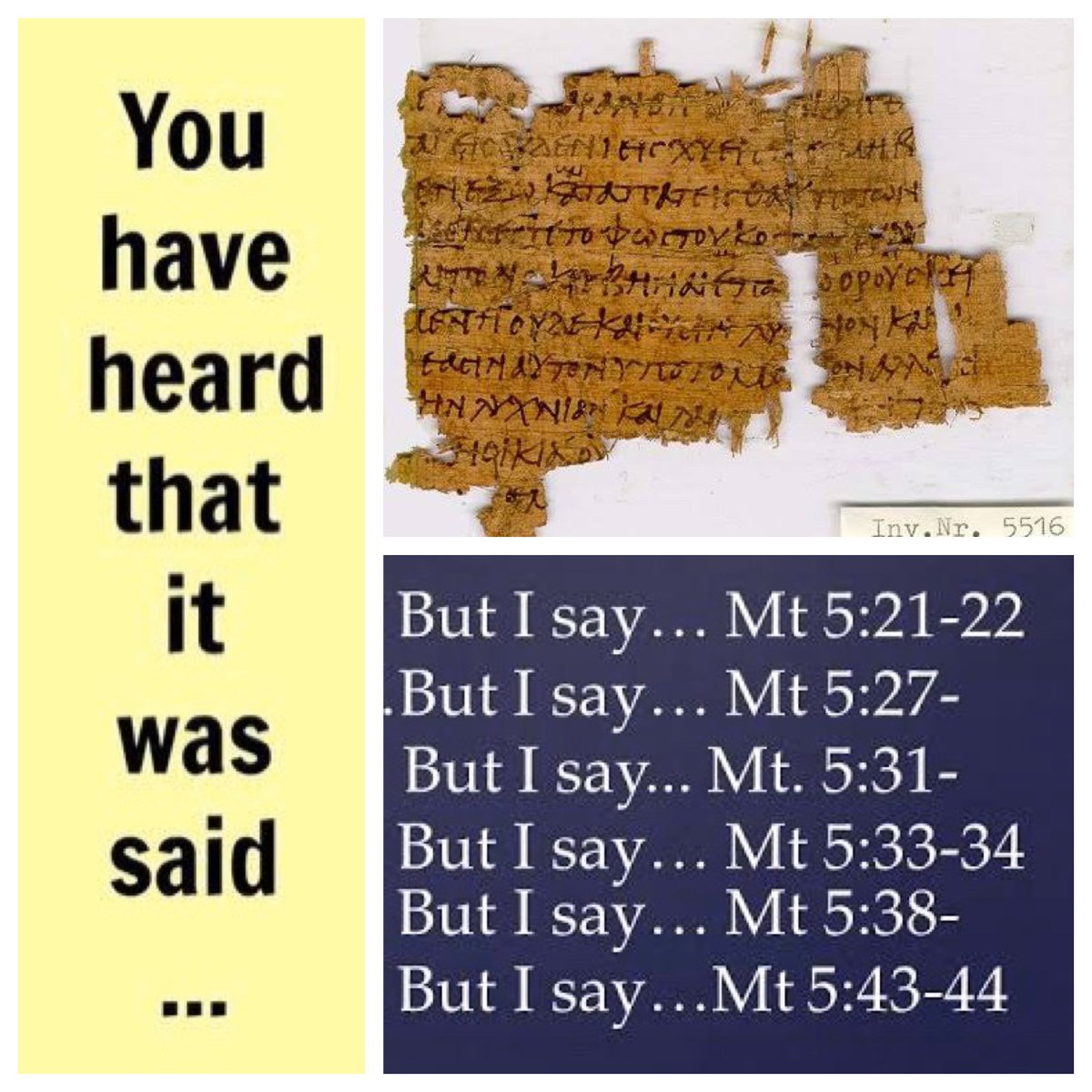

https://johntsquires.com/2020/02/13/you-have-heard-it-said-but-i-say-to-you-matt-5/

https://johntsquires.com/2020/02/06/an-excess-of-righteous-justice-matt-5/

https://johntsquires.com/2020/01/30/blessed-are-you-the-beatitudes-of-matthew-5/