During the long season after Pentecost in Year C, the lectionary includes a range of stories and oracles from the prophetic texts of Hebrew Scripture. The first three come from the books bearing the title of Kings—although the contents of these two books canvass more than the kings of Israel; prophets figure prominently at key points in the story.

Two of these passages are well-known because Jesus refers to them in the sermon he delivered at Nazareth: Elijah and the widow at Zarephath, and Elisha and the Syrian army commander, Naaman. Elijah is sent to a faithful woman, who perhaps typically remains unnamed; Elisha is sent to faithful man, identified by name as Naaman (Luke 4:25–27).

Both characters demonstrate trust in the stories told about them. The woman trusted Elijah when he said, “first make me a little cake of it and bring it to me, and afterwards make something for yourself and your son” (1 Ki 17:13). She did this, and there was enough for her and her son, and for Elijah “for many days … the jar of meal was not emptied, neither did the jug of oil fail” (2 Ki 17:15–16).

The army commander (eventually) trusted Elisha when he said, “go, wash in the Jordan seven times, and your flesh shall be restored and you shall be clean” (2 Ki 5:10). After an initial reluctance, Naaman did as the prophet said, and he was healed; “his flesh was restored like the flesh of a young boy, and he was clean” (2 Ki 5:14).

The woman, who was not an Israelite (Zarephath is in Sidon, a Gentile territory) is of low social status; the army commander, of course, is a high status person, even if he is a foreigner, as a Syrian. Jesus alienates his audience in Nazareth by focussing his attention on God’s merciful care for foreigners like the widow of Sidon and the soldier of Syria, regardless of their social status—and on the way each one of these foreigners modelled trusting obedience. As Luke reports, his audience was not impressed!

See more at

We hear the second of these stories this coming Sunday: the encounter between the prophet Elisha and the general Naaman is what is in the Hebrew Scriptures passage proposed by the lectionary. The story comes after Elisha has taken on the role of prophet in the kingdom of Israel, following on from Elijah. Elisha asked Elijah to grant him a double share of his spirit (2 Ki 2:9); Elijah agreed, and after Elijah departed, a company of prophets declared “the spirit of Elijah rests on Elisha” (2:15).

So, as I noted in last week’s blog post, Elisha performs miracles that replicate those performed earlier by Elijah; but he does more than Elijah, with an abundance of miraculous deeds. This particular miracle is given more space than any other miracle that either prophet performs.

The early and substantive miracle of Elijah, his reviving the widow ‘s son (1 Ki 17), is told in eight verses; the story of Elisha and Naaman (2 Ki 5) takes up fourteen verses, but the story continues for another thirteen verses, detailing the consequences for Elisha’s servant Gehazi after his intervention into the sequence of events.

The lectionary, of course, does not offer all of the elements of this long narrative. We hear, firstly, the opening two verses which introduce Naaman and his situation; we then skip to verse 6, to hear the course of events leading to the healing of Naaman. Whilst verse 2 also introduces a young Israelite girl who had been taken captive to serve Naaman’s wife, we do not hear her role in the narrative offered by the lectionary (vv.3–5). The lectionary, unfortunately, is good at minimising or informing female characters in the stories it includes.

As for Naaman, we learn much and observe much during the course of events. Naaman is introduced in a distinctive way. He is a “mighty warrior”, a commander “of the army of the king of Aram”—that is, a foreigner—who was “in high favour with his master, because by him the Lord had given victory to Aram” (5:1). Aram was a province in Syria, to the northeast of Israel, with Damascus as a key city. The province is perhaps best known through the fact that its name forms the basis of the language which came to be the dominant tongue across the Middle East: Aramaic.

In the days of Israel’s kings and prophets, foreigners were inevitably regarded as enemies, to be fought, subdued, and held captive. The regular battles recorded throughout the books of Samuel and Kings attest to this, and many psalms also reflect this deep-seated antagonism.

One psalmist sings “rise up, O Lord, in your anger; lift yourself up against the fury of my enemies” (Ps 7:9), another affirms that “surely God is my helper … he will repay my enemies for their evil” (Ps54:4–5), while yet another celebrates at length: “you made my enemies turn their backs to me, and those who hated me I destroyed. They cried for help, but there was no one to save them … I beat them fine, like dust before the wind; I cast them out like the mire of the streets” (Ps 18:40–42).

In the NRSV, no less than ten psalms have been given titles which include the words “Deliverance from Enemies” (Pss 4, 5, 10, 13, 31, 35, 59, 70, 140, 143). It was a standard element, it would seem, that was to be found in temple worship and in the prayers of faithful people, as these psalms attest.

This is one factor that helps explain the intractability of national relationships in the Middle East today; centuries of antagonism and conflict have led to hatred and demonising of the “other”. There is no clear and simple way back from this deeply-ingrained perspective, held by Jew and Arab alike.

In the context provided by these psalms, the celebration of Naaman as a military commander whose victory was enabled by the Lord God of Israel is striking. Whether Naaman was an historical person or not cannot be determined; his actual existence is as secure, or as fragile, as the existence of any other figure in the narratives found in the grand saga of Israel in these biblical books. There are no known references to him in sources outside the biblical texts.

To be sure, the story, first told by storytellers and then passed on through the growing oral tradition, would have struck a distinctive note in ancient Israel, given this ingrained antagonism towards foreigners—especially those in military service. By the time the Deuteronomic History was compiled and published, the Israelites had already experienced the beneficence of Cyrus, King of Persia. Under Cyrus—declared by the Lord in Second Isaiah to be “my shepherd [who] shall carry out all my purpose” as the Lord’s anointed (Isa 44:28, 45:1)—Israel had experienced a positive action by a foreign ruler. Naaman’s victory, empowered by the Lord God, would have had a resonance with that experience for this who heard, or read, his story.

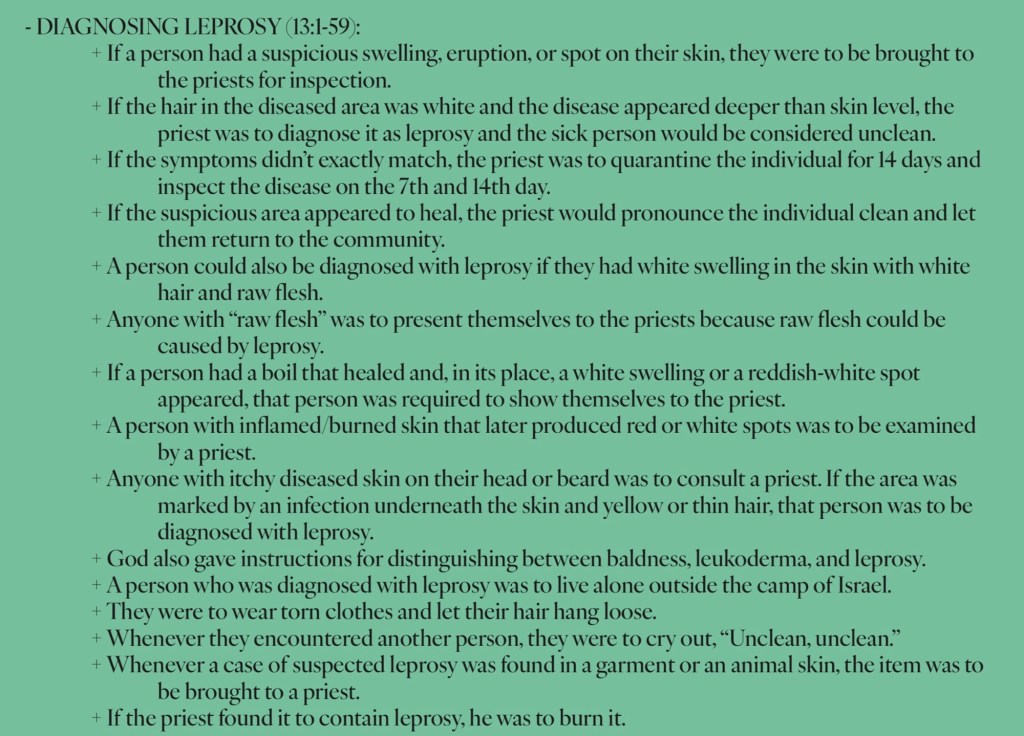

But Naaman is also introduced as a mezora, a person affected by the skin disease tzaraath (2 Ki 5:1). This latter term is traditionally rendered as “leprosy”, but it is clear that it was not at all what today we know as Hansen’s disease, a highly-contagious disease in which a bacterial infection can damage some or all of a person’s skin, nerves, eyes, and their respiratory tract. Biblical leprosy was, rather, a disfiguration of a person’s skin—usually manifested in white patches of skin—which rendered a person ritually unclean. There are a range of prescriptions for dealing with this disease in Lev 13–14.

Naaman’s condition renders him unclean in Israelite society. It is his his slave girl (taken into service from her home in Israel) who suggests to him that he might visit “the prophet who is in Samaria”, for “he would cure him of his leprosy” (5:3). Naaman goes to Elisha with the blessing of his king, whose army had previously been at war with the Israelite army (1 Ki 20, 22); now, however, Israel was battling the Moabites to the south (2 Ki3), so Aram was a beneficent neighbour.

The process that Elisha sets for Naaman to follow is symbolically rich and practically powerful. “Go, wash in the Jordan seven times, and your flesh shall be restored and you shall be clean” (5:10), the prophet commands him. The “seven times” signals a perfect, completed process, typical of Israelite practices (“seven times” appears four times in the ritual of Lev 14, and another five times in other ritual elsewhere in Leviticus).

This process is far simpler than the required ritual for Israelites: Leviticus prescribes a far more complex process. It begins with an investigation by the priest to determine whether the person is in fact unclean (Lev 13, with multiple options for consideration set out in the first 46 verses, and then 13 further verses relating to clothing and houses!)

If the disease is still active, a purification process then ensues in which “two living clean birds and cedarwood and crimson yarn and hyssop” are to be brought to the priest, who will then slaughter one bird and “take the living bird with the cedarwood and the crimson yarn and the hyssop, and dip them and the living bird in the blood of the bird that was slaughtered over the fresh water” (Lev 14:4–6). This blood is then sprinkled seven times on the one who is to be cleansed of the leprous disease; “then he shall pronounce him clean, and he shall let the living bird go into the open field” (Lev 14:7).

A further process is then required, with the person to be healed washing, shaving, living apart for a week, shaving again, and then taking another collection of items for this ritual: “two male lambs without blemish, and one ewe lamb in its first year without blemish, and a grain offering of three-tenths of an ephah of choice flour mixed with oil, and one log of oil” (Lev 14:10). Another ritual of sacrifice follows, with detailed instructions given (Lev 14:11–20). It is complex!

The response of Naaman, in the light of this complex process expected of Israelites, is striking. He is impatient! He had actually been expecting an instantaneous cure, and wondered why he could not simply was in a river closer to his home (2 Ki 5:12). In his anger, he dismisses Elisha as weak and ineffective (5:11–12). But after an intercession from his servants, he dutifully obeys, and the result (after seven immersions) is dramatic: “his flesh was restored like the flesh of a young boy, and he was clean” (5:14). Naaman returns to Elisha, to praise the God who has enabled the prophet to heal him and to offer a gift (5:15).

Why does the lectionary end the section of the text offered for this Sunday (5:1–14) before the following verse? Surely to end the section with the climactic confession, “I know that there is no God in all the earth except in Israel” would have been quite powerful! Perhaps it stops abruptly to avoid the apparently embarrassing words of Naaman, “please accept a present from your servant” (v.15b). This was to be expected in the patron—client society of antiquity; is it felt a little crass for modern ears, or does it unhelpfully suggest that grateful parishioners today should shower their ministers with gifts in gratitude? (That would be contrary to the Code of Ethics that I am bound to operate by.)

Or perhaps because the last part of this verse introduces a whole new act in the story of Naaman and Elisha? The suggestion of a gift for the prophet, his stern refusal (vv.16–18) and his final word of peace (v.19), all lead on into the final part of the long story told in this chapter. It takes us to Gehazi, the interfering servant of Elisha, and the consequences of his actions which are recounted in vv.20–27. Again, the lectionary ignores this part of the story; but its inclusion in the Deuteronomic History indicates that it had significance for the Israelites in subsequent years, and especially in the years after the Exile, when this lengthy document was put into a final form.

Elisha, in the end, is required to pronounce judgement over the miscreant servant. Gehazi intervenes, seeking additional money from Naaman—who willingly gives more than what is asked for. “Please give them a talent of silver and two changes of clothing”, the servant begs; Naaman responds by giving him “two talents of silver in two bags, with two changes of clothing” (5:22–23). So gratified was the Syrian for his healing that he gave in abundance.

But Elisha knows what his servant has done; “did I not go with you in spirit when someone left his chariot to meet you?”, he says (5:26). And so the story ends with a clear reversal: “the leprosy of Naaman shall cling to you, and to your descendants forever”, the prophet tells his servant (5:27). And so it does. The man who was once leprous is now healed, for “his flesh was restored like the flesh of a young boy, and he was clean” (5:14); whereas Gehazi now bears the stigma of Naaman’s leprosy, and as he departs from Elisha, “he left his presence leprous, as white as snow” (5:27).

In later Jewish tradition, the figure of Gehazi serves as a type for those who are avaricious in their dealings with others, as Gehazi was. An article in the Jewish Encyclopedia describes how he is portrayed in the Babylonian Talmud: “When Naaman went to Elisha, the latter was studying the passage concerning the eight unclean “sheraẓim” (creeping things; comp. Shab. xiv. 1).

“Therefore when Gehazi returned after inducing Naaman to give him presents, Elisha, in his rebuke, enumerated eight precious things which Gehazi had taken, and told him that it was time for him to take the punishment prescribed for one who catches any of the eight sheraẓim, the punishment being in his case leprosy. The four lepers at the gate announcing Sennacherib’s defeat were Gehazi and his three sons (b.Soṭ 47a).”

Gehazi is also identified as one of four individuals who deny the resurrection of the dead and have no portion in the world to come (b.Sanh 90a). See https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/6557-gehazi

In a Christian context, we might also note that the dynamics of this story in 2 Kings 5 foreshadow the dynamics of true faith spoken of by a later teacher in Israel: “whoever wants to be first must be last of all and servant of all” (Mark 9:35); “the greatest among you must become like the youngest, and the leader like” (Luke 22:26); “blessed are you who are hungry now, for you will be filled; blessed are you who weep now, for you will laugh … woe to you who are full now, for you will be hungry; woe to you who are laughing now, for you will mourn and weep” (Luke 6:21,25). What a pity the lectionary has omitted this potent conclusion to a well-known story.

See also