I have recently taken part in a most interesting series of conversations, on topics that are quite unlike others that I have participated in. I’ve been one of three members of the “Moon Knight Panel”, discussing the six episodes of this show, Moon Knight, which was released earlier this year on Disney Plus. The three of us—Will in Melbourne, Praxis in Hobart, and myself in Canberra—have recorded a series of seven podcasts that explore the issues that arise in each of the six episodes of Moon Knight. (Seven podcasts for six episodes, as the first podcast is an introduction to the panel members.)

The six episodes were released by Marvel Entertainment, which began life as the publisher of comic books (Spider Man, Doctor Doom, Captain America, She-Hulk, and Wolverine, amongst many others). It has now expanded to be a film production enterprise. Moon Knight is a character in Marvel comics, and this series represents a stepping-up from the role that Moon Knight has had in the printed comic books, for this character to become the star of his own television miniseries. The six episodes contain action, adventure, violence, drama, and suspense—it’s a really well-done artistic creation.

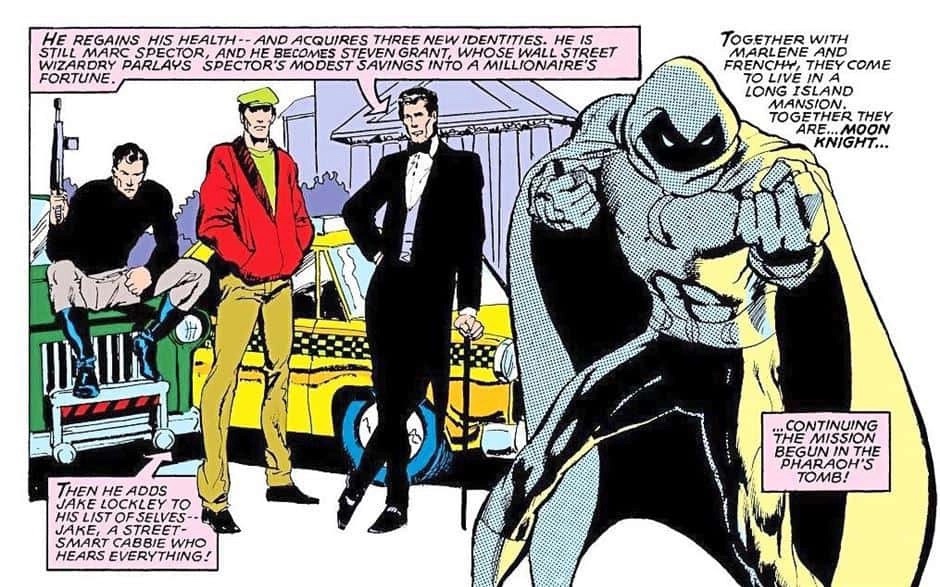

Moon Knight first appeared as a character in a 1975 comic, Werewolf by Night #32, where his character was a villain, aiming to kill Werewolf. Moon Knight continued to appear in various comics in subsequent years, in which he turns to become a “good guy”. His first solo series, Moon Knight #1, was published in 1980. There is a whole complex story that has evolved over the decades, as Moon Knight has appeared, as himself and in various guises, in various comic series during that time. I entered into this podcast series, however, in blissful ignorance of that long history of Moon Knight; I was viewing the episodes with Paul Ricouer’s “first naïveté”.

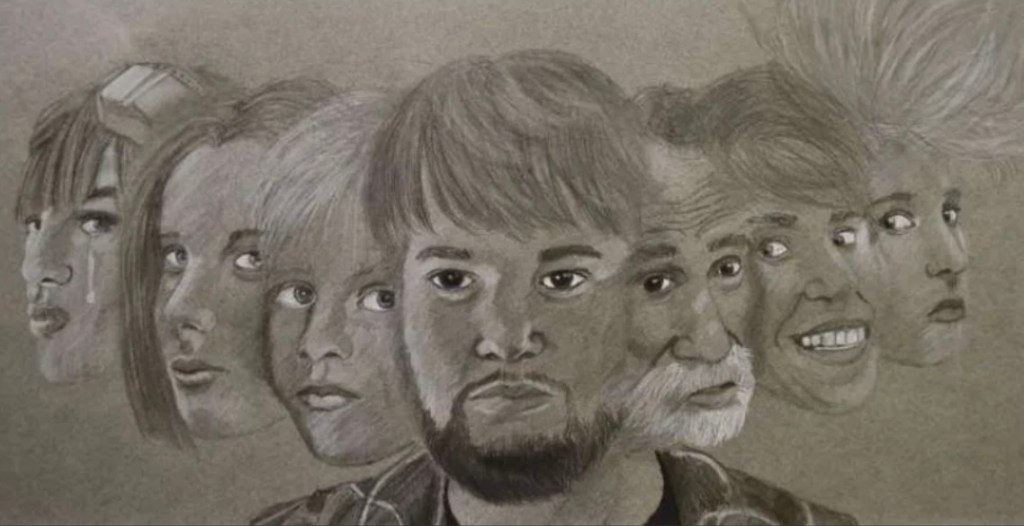

My involvement in the panel has come about, not because I am a Marvel comic aficionado—I am not—nor because I am a Disney Plus subscriber—I am not—and not even because I am an action movie buff—I most certainly am not! It was because the episodes reveal a situation in which the human character who is to the fore at the start of the first episode, mild-mannered British gift-shop employee Steven Grant, is revealed to have Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), and DID is something that I know about quite closely, from my own lived experience of the condition.

Steven Grant actually turns out to have been an identity created by Marc Spector, a Jewish-American mercenary who has been implicated in numerous murders. The series provides a gradual revelation of the relationship between Marc and Steven—and by the last episode, leaving us on the expected cliffhanger, we are aware that there is yet another identity, Jake Lockley, lurking in and around Marc and Steven. Jake is a ruthless Spanish assassin; how he figures in the complex scenario will, we presume, be revealed in the second series, yet to be recorded (although readers of the printed comics will have a good understanding of this already).

*****

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) was previously known as MPD (Multiple Personality Disorder), and it was MPD that I was diagnosed with about 30 years ago. The process of therapy that led to this diagnosis was a thoroughly challenging and deeply disturbing process for me. The therapy that followed, enabling me to deal with the dissociated identities that were lurking in my being, was a comprehensive and exhausting marathon over some years. I haven’t spoken about this before to many people in my life—and certainly never in such a public way as I have in the podcasts and now in this blog.

The series does a fine job, in my estimation, of portraying the confusion, disturbance, incomprehensibility, and fear that comes with a diagnosis of DID. Although I did not have many dramatic experiences of suddenly finding myself in a foreign and unknown situation—which is what happens, very dramatically, to Steven Grant in the earlier episodes—I certainly had the experience of complete and absolute confusion, of finding myself “gripped” in an intense way by a personality or force that felt quite alien, of enacting behaviours that were completely uncharacteristic for me and deeply troubling for others. All of these things are portrayed with vivid drama in the Moon Knight series—far more dramatically than what my own experiences were, but resonating deeply with the experiences I had, which still remember very clearly.

One of the other members of the Moon Knight panel, Praxis, also has lived experience of DID—although his experience is very different from mine. The “system” of Praxis that he is living with is quite different from the “system” that I identified in my therapy. His personalities identify in ways very different from the ways that mine did, and his “living with a ‘functioning multiplicity’ system of identities” is very different from the process that I undertook, of “fusing personalities piece-by-piece, seeking an ultimate integration into one person”. Talking with one another about our rather different experiences of DID has been mutually beneficial—and even through the differences, there are many key similarities that we have shared.

The series also accurately depicts the sheer exhaustion of the process of “switching” identities—something that was a very real experience for me in the height of the time when my “personalities” were emerging. Such “switching” would happen without warning, many times in a fierce, dramatic way. The sense of suddenly being “taken over” by another identity was an intensely draining experience for me, even when it happened in a relatively “smooth” way. So the dramatic portrayals of this aspect in Moon Knight, whilst not entirely “realistic” for me, certainly convey the intensity and dramatic impact of how such experiences felt at the time.

One critic of the comic book character made this assessment a few years ago: “When you look at Moon Knight’s story as a whole, it appears to be more and more of a story about perseverance, endurance, and coming to grips with who you are. That’s an extremely universal story. That’s something anyone can relate to, in one way or another. It’s a call to believe in yourself, and to never give up. And, really, that’s one of the most heroic tales you can get.” (Matt Attanasio, https://comicsverse.com/moon-knight-mental-health/, 22 May 2018)

That is a very positive and affirming conclusion for me to take from this story, and from my own experience. I hope that this is sensed by those who watch the television series. You don’t need to have experienced the condition of DID to take this lesson to heart.

The link to the first podcast (introducing the Moon Knight Panel) is at https://open.spotify.com/episode/5feSJb2qyVAhzBEfoeHj1x?si=29983b58d694477d

The podcast on Episode One is at https://open.spotify.com/episode/0Rk2PZKSvqKcc7yigju8pn?si=f7tXj0jnRk2ph9o1UpgKSw

I invite you to have a listen and explore these fascinating (and challenging) issues.

Good information about DID can be found at https://www.sane.org/information-and-resources/facts-and-guides/dissociative-identity-disorder