Every Sunday throughout the Christian year (save for the six Sundays in the season of Easter), the Revised Common Lectionary provides a passage from Hebrew Scripture as the First Reading in the set of four readings for that Sunday. (During Easter, a passage from Acts stands as the First Reading, providing stories from the early years of the movement which Jesus founded.)

Each year, during the season of Epiphany, the First Readings relate to the prophetic figures of ancient Israel. In Year A (this year), almost all of them are drawn from the book of Isaiah the prophet, with one from Micah and one from Deuteronomy (where the link is with Moses, the great prophet).

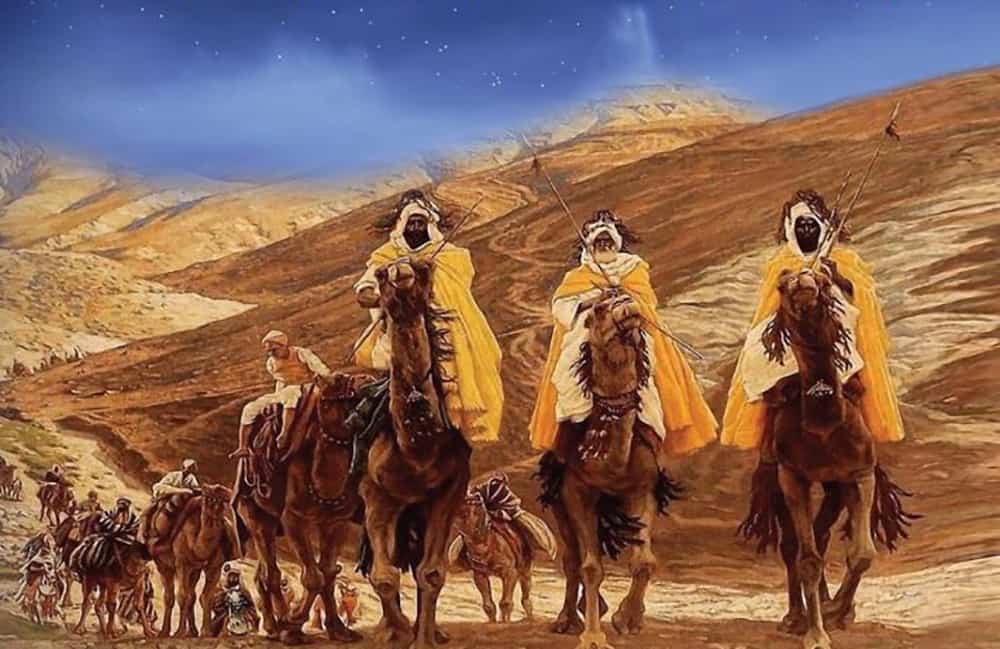

Each year, the Feast of Epiphany includes Isaiah 60:1–6 as the First Reading. In this passage, the prophet foresees that “nations shall come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn” (Isa 60:3); he specifies that when they come to the light of the Lord, “they shall bring gold and frankincense,

and shall proclaim the praise of the Lord” (Isa 60:6). The reason for reading this on Epiphany is obvious—it correlates well with the story in Matthew of when the magi came to visit Jesus, and “they offered him gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh” (Matt 2:11).

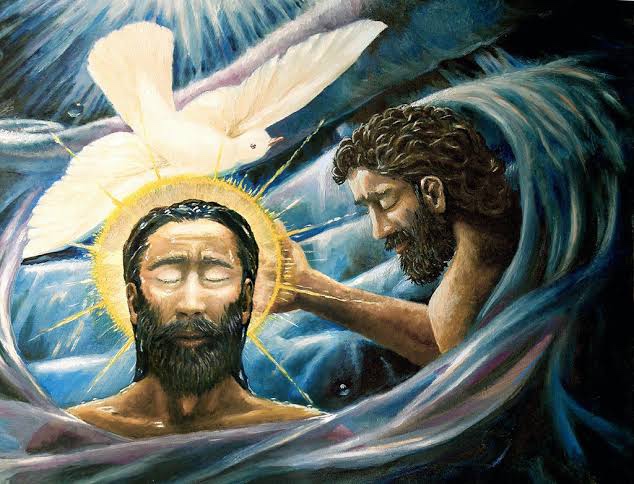

The first Sunday after the Feast of Epiphany is always the day on which the Baptism of Jesus is recalled. One year (Year B) places the beginnings of the priestly creation account (Gen 1:1–5) alongside this Gospel story. In the other two years, passages from Second Isaiah are offered; in Year C, this is Isaiah 43:1–7, which includes the affirmation, “do not fear, for I have redeemed you; I have called you by name, you are mine; when you pass through the waters, I will be with you” (Isa 43:1–2). The presence of water in both of these passages seems to be the reason for their linking with the baptism of Jesus.

This year, Year A, the prophetic excerpt is the first of four songs that are linked explicitly with the Servant (42:1–9; 49:1–7; 50:4–11; and 52:13–53:12). In this first song, the Servant is designated as the one in whom God delights (42:1); the phrase recurs in the message of the voice from the cloud which speaks at the baptism of Jesus, declaring that he is the one “with whom I am well pleased” (Matt 3:17).

The song also affirms that the Servant has God’s spirit within him (Isa 42:1), something which is directly enacted in the baptism of Jesus when he “saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and alighting on him” (Matt 3:16). It is clear, therefore, why this passage has been selected for this day.

On the ensuing Sundays, we are offered two further sections from Isaiah (Isa 49 and Isa 9), a famous passage from Micah 6, another passage from Isaiah (Isa 58), and then a section of the lengthy speech attributed to Moses after the covenant renewal ceremony (Deut 29–30), in which he speaks like a prophet: “I have set before you life and death, blessings and curses; choose life so that you and your descendants may live” (Deut 30:19).

The four prophetic passages that appear in weeks two to six this year offer some striking words from the times of ancient Israel. Their inclusion in a key lectionary of the Christian churches alongside Gospel passages recounting the early period of the public activity of Jesus invites us to appropriate these passages as pointing to Jesus as God’s chosen one (messiah).

This is particularly evident in this Sunday’s passage (Isa 49:1–7), where a number of elements have been interpreted as predictors of the role that Jesus undertook. There are six different elements in these seven verses which can be seen to serve as such predictors, pointing forward to Jesus.

The one who sings this song is declared by God to be God’s servant (49:3), in the same way that Jesus is acknowledged as servant (Acts 3:13, 26; 4:27, 30). The song was originally composed and sung during the Exile in Babylon, as the prophet looked to a return to the land of Israel and the resumption of Israel’s role as God.

See

This servant has an awareness that he has been chosen before his birth for his role (49:1, 5), a sense that is conveyed in the Gospel narratives that variously indicate God’s plan and purpose for Jesus was conveyed to his mother (Luke 1:32–33), his father (Matt 1:21), and then both parents (Luke 2:34–35, and 3:38). The sense of a purpose for Jesus that was determined long before his activities in Galilee and Jerusalem is also evident in the prologue to the book of signs (John 1:9–14) and in a later controversy reported in that book (John 8:42, 58).

The servant is the one in whom God would be glorified (49:3), pointing to a key theme in the book of signs, where the function of Jesus is to glorify God (Jon 17:1–5). The servant will gather Israel back to God (49:5), “to raise up the tribes of Jacob and to restore the survivors of Israel” (49:6). This is the mission that Jesus declares when he asserts that “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matt 10:24), and is inherent in his charge to the disciples, “you will sit on thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel” (Luke 22:30).

This particular servant song also includes two key statements which figure prominently in the orderly account of the early church which is told in two volumes and is attributed to Luke. First, the servant is told by God, “I will give you as a light to the nations” (49:6)—an image that is picked up by three evangelists. Simeon declares that Jesus will be “a light for revelation to the Gentiles and for glory to your people Israel” (Luke 2:38). The Johannine Jesus affirms of himself, “I am the light of the world” (John 8:12; 9:5). And the Matthean Jesus then extrapolates the image, telling his disciples, “you are the light of the world” (Matt 5:14).

Then, the servant is told that God has given him that light “that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth” (49:6). This phrase occurs in the definitive statement of the risen Jesus, in the second Lukan account of the ascension of Jesus, when he charges his followers, “you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8); the phrase recurs when this servant song is later quoted by Paul (Acts 13:47).

When we look back at this text, through the prism of Jesus, we can see just how well it seems to speak of Jesus. In Christian understanding, he was indeed the Servant, chosen by God, glorifying God in his life and his death, recalling Israel to their covenant with God, and shining as a light that would bring the good news of salvation to the ends of the earth. The text looks to be a clear prediction of Jesus.

And yet, interpreting this passage and other ancient Israelite prophetic passages as predictive of Jesus is a strategy that we should undertake with care. Christians have a bad track record of taking Jewish texts and Christianising them, talking and writing and thinking about them as if they were always intended simply to be understood as Christian texts. But first of all, they were Jewish (or, to be precise, ancient Israelite texts).

So the original setting of such passages needs always to be considered—the historical, social, political, cultural contexts in which they came into being, as well as the literary genre being used and the linguistic and literary conventions being deployed. Obliterating the original setting and acting as if the text was intended for a time many centuries later, is unfair and unethical.

Indeed, Christianising Old Testament texts can well become the first step in a dangerous process, as we firstly remove Judaism from our interpretive framework, and then treat the prophetic text as having nothing to do with Judaism, and everything to do with Christianity. This is the pathway that can lead to supercessionism—a view that Christianity has superseded and indeed replaced Judaism—and even antisemitism—actively speaking and acting against Jews and Judaism. And having arrived at such a destination, we are reinforced in our pattern of ignoring and obliterating the earlier meanings in the text.

Texts (whether biblical or other literature) are always multivalent—that is, open to being interpreted in a number of ways, offering multiple ways of understanding them. That’s why we have sermons, and don’t just read the biblical text and then put it down. We keep it before our minds, and explore options for understanding and appropriating it. Ignoring the multiple layers of meaning inherent in biblical passages is a reductionist and self-centred way of undertaking interpretation. Reducing the prophetic texts to predictive declarations solely about Jesus is a poor interpretive process.

See also