On Easter Sunday, we say: “Christ is risen! He is risen indeed!”, to celebrate that “God raised Jesus from the dead” (Gal 1:1; Rom 4:24; 10:9; Acts 2:32). Paul affirms this good news in this extract from his first letter to the saints in Corinth, which is the Epistle reading that the lectionary offers for Easter Sunday (1 Cor 15:1–11). Some verses in this passage have played a key role in the development of Christian tradition, which affirms in creeds and confessions a belief in “Jesus Christ … who was crucified, died, and was buried … who rose again from the dead on the third day”.

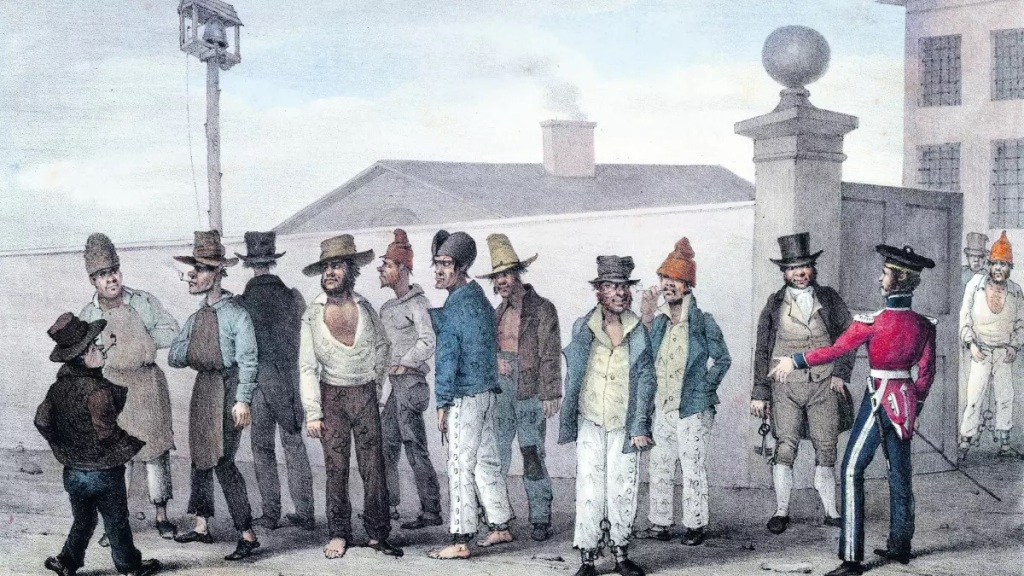

What is the nature of the confessional affirmation that Paul offers in this passage? The previous chapters of 1 Corinthians have alerted us to the disorganised ethos of the community in the cosmopolitan port city of Corinth. Those earlier chapters have indicated a number of problems that existed within the community of followers of Jesus. There was factionalism (chs.1–4), immorality (ch.5), resorting to civil lawsuits (ch.6), and dissension regarding marriage, celibacy, and sexuality (ch.7). There were differing attitudes towards consuming meat bought in the marketplace after it had been offered to idols (chs.8–10), and multiple issues that manifested in their gatherings for worship (chs.11–14).

Paul addresses each of these matters with the same intention, to bring about order in the midst of the chaos that he has been told about. His words in the midst of the lengthy discussion about marriage, celibacy, and sexuality state his purpose with clarity: “I say this for your own benefit, not to put any restraint upon you, but to promote good order and unhindered devotion to the Lord” (7:35).

The disorder and chaos evident in worship, in particular, led Paul, in the chapter immediately preceding this passage, to advise the Corinthians to seek to speak to others in worship “for their upbuilding and encouragement and consolation” (14:3). He advises them to exercise their spiritual gifts appropriately; to “strive to excel in them for building up the church” (14:12), to “not be children in your thinking … but in thinking be adults” (14:20). He advises them, “let all things be done for building up” (14:26), noting that “all things should be done decently and in order” (14:40), for “God is a God not of disorder but of peace” (14:33).

People speaking over the top of each other in worship, not attending to important words of prophecy and tongues, reflected the disordered chaos of the apparently quite libertine community. The infamous words ordering women to “keep silent” (14:33b—36), along with the adjacent commands to “keep silent” while one interprets tongues that are spoken (14:27–28) and “keep silent” to those seeking to offer a word of prophecy while others are still prophesying (14:29–31), are included in this letter precisely to address this chaotic disorder. And not for the first time in this letter, Paul invokes his higher authority to support his directions: “[you] must acknowledge that what I am writing to you is a command of the Lord” (14:37; see also 5:3–4; 7:40; 10:20–22; 11:27–28; 16:10; and cf. 7:25).

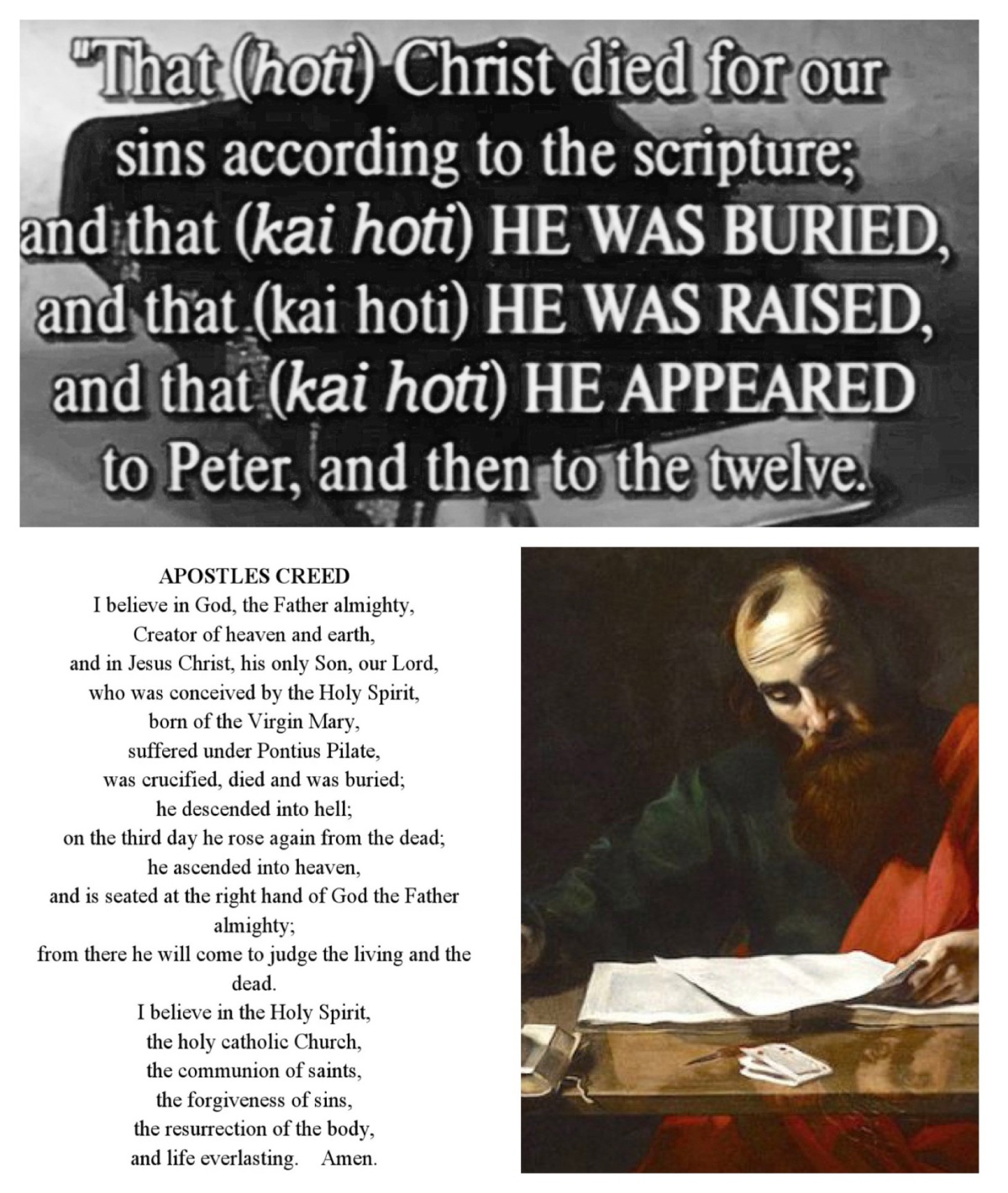

Immediately after this extensive discussion about worship, Paul turns to his foundational message about Jesus, in a four-part statement: Christ died—was buried—was raised—and then appeared to various people (15:3–5). He uses terms that denote the passing on of traditions: “I received … I handed on … which you received … in which you stand” (15:1); and he insists on the importance of what he passes on: “you are being saved, if you hold firmly to the message that I proclaimed to you” (15:2). These two verses provide a strong, insistent introduction to what follows in the ensuing verses.

We see this dynamic also in an earlier chapter, in the familiar words associated with the Last Supper: “I received from the Lord what I also handed on to you” (1 Cor 11:23), as well as in the commendation of the Corinthians as they “maintain the traditions just as I handed them on to you” (11:2).

The core tradition that Paul cites is the fourfold declaration that Jesus died, was buried, was raised, and appeared (vv.3–5). It may have already have been an existing formula; we know that Paul, in this letter and elsewhere, makes use of very short credal-like statements that it is likely had already been developed by others, some of which he cites in order to refute, such as: “is well for a man not to touch a woman” (7:1), “all of us possess knowledge” (8:1), “all things are lawful” (10:23), and “how can some of you say there is no resurrection of the dead?” (15:12).

There are other succinct sayings which Paul uses as the basis for further developments in his argument, such as “I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ, and him crucified” (2:2), “knowledge puffs up, but love builds up” (8:1), “there is no God but one” (8:4), and “all things are lawful, but not all things build up” (10:24). The discussion of factions in chs.1–4 is built off “I belong to Paul … I belong to Apollos … [but] what then is Apollos? what is Paul?” (3:4–5), while Paul’s lengthy discussion of spiritual gifts (12:4—14:40) jumps off from the unspiritual “Jesus be cursed!” and the spirit-inspired response, “Jesus is Lord” (12:3).

Furthermore, Paul writes a number of longer credal-like statements, some of which seem shaped for liturgical usage: the words which became the “words of institution” in the church’s eucharistic practice (1 Cor 11:23–26), and others such as Rom 8:28; 2 Cor 4:14; Gal 1:3–5; Phil 2:6–11. The writers in the school of Paul who later wrote letters claiming to have his authority ( the “pastoral epistles”) followed this practice (see 1 Tim 2:5–6; 3:16; 2 Tim 2:11–13; Titus 2:11–14).

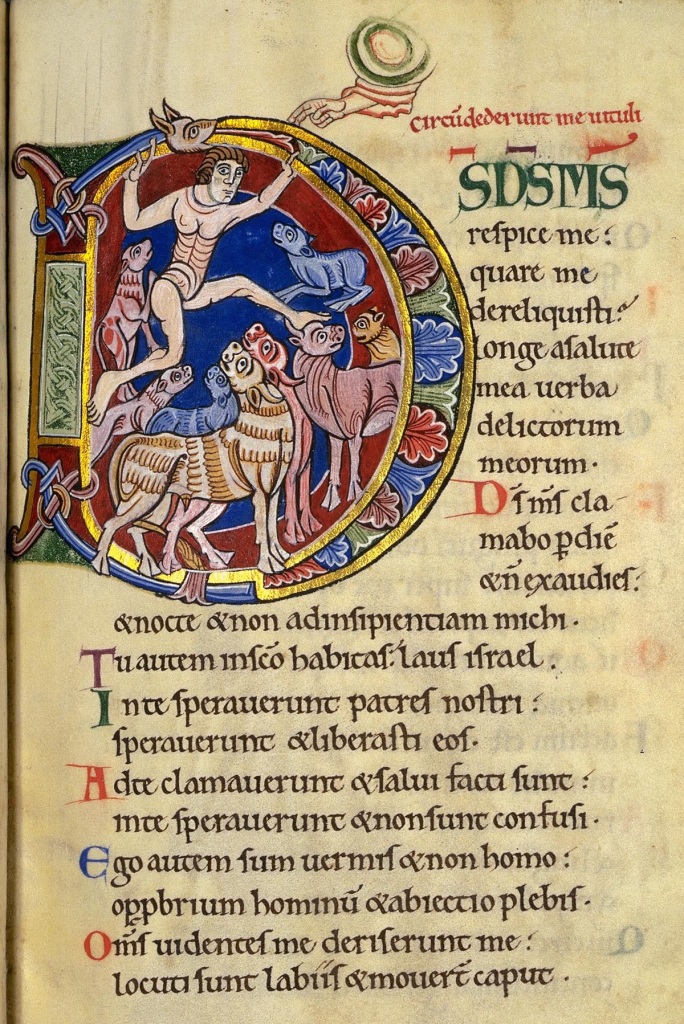

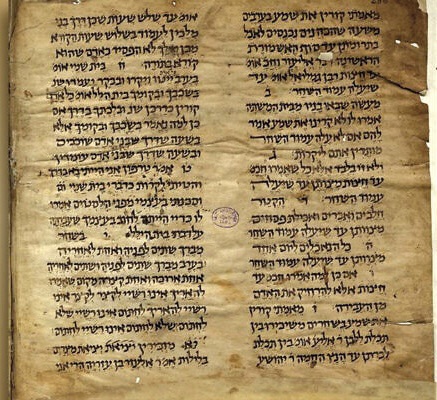

Two clauses in Paul’s tradition-based affirmation of 1 Cor 15:3–5 are buttressed by reference to scripture, another voice of authority alongside “the tradition”. What the specific scripture passages are, Paul does not state; this has left open the door for speculation by later interpreters.

Supporting arguments by reference to scripture is not unknown in Paul’s writings; as a Pharisee, he had attained a good awareness of Torah and its application to life (see Gal 1:14; Phil 3:5–6). He bases his magnum opus, Romans, on a scripture citation (Rom 1:17, citing Hab 2:4) and there is barely a chapter of this letter that does not contain scripture quotations and allusions in abundance.

Key moments in 1 Corinthians are likewise supported by verses from Hebrew Scripture (1 Cor 1:19, 31; 2:9, 16; 3:19–20; 14:21; 15:54–55), and the well-known “words of institution” themselves (11:23–26) reference the tradition which emerges in later decades in the Synoptic Gospels, recording the words of Jesus himself at the last supper (Mark 14:22–25; Matt 26:26–29; Luke 22:14–20).

By using the terminology of traditions being received and handed on, Paul is reining in the wayward Corinthians, recalling them to the fundamentals of their faith. So he sets out the dynamic of died—buried—raised—appeared (15:3–5) as the foundation for then discussing, in the remainder of the chapter, issues associated with the resurrection of Jesus (15:6–58).

Who saw the risen Jesus? First, Paul tells of an appearance to the early leaders, Cephas (Peter) (v.5) and James (v.7)—of which, neither appearance is reported in any Gospel. Then, Paul indicates that Jesus appeared to “the twelve” (v.5) and “all the apostles” (v.8)—apparently alluding to narratives found in the later texts of three Gospels Matt 28:16–20, Luke 24:33–48; John 20:19–23, 24–29; 21:1–14. (The appearances narrated in the shorter and longer endings of Mark, added after 16:8, are not relevant; these are later patristic additions based on the other three Gospels, designed to harmonise the ending of Mark with these others.) Acts 1:6–11 might also be relevant here.

An interesting question is, how did he distinguish between these two groups—“the twelve” on the one hand, and “all the apostles” on the other. Indeed, these terms appear to be inherited by Paul from earlier traditions. This is the only place in all Pauline letters which refer to “the twelve”; and besides, the Gospel narratives noted above do not have Jesus appearing to “the twelve”, as Judas was absent from all of them, and so was Thomas in John 20:19–23.

As far as the word “apostle” is concerned, in 16 of the 18 occurrences in the Pauline corpus (including those not authentic to Paul) Paul explicitly apply the term to himself. Paul acknowledges others as apostles: James (Gal 1:19), Peter (Gal 2:8), perhaps Barnabas (1 Cor 9:1, 5–6), an unspecified number of believers who were given gifts to be apostles (1 Cor 12:28–29; see also Eph 4:11), and most strikingly, Andronicus, a male, with Junia, a female (Rom 16:7). Are these the people that Paul has in mind at 1 Cor 15:8? Or is this simply a phrase inherited from the tradition, which Paul has repeated?

Next, Paul identifies an appearance to “more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time” (v.6), which again has no place in any Gospel account. Last, Jesus appears to Paul himself (v.8), which he briefly reports at 1 Cor 9:1 and Gal 1:1. Strikingly absent from his list is the empty tomb and the appearances to Mary in the garden (John 20:14), to the women as they left the tomb (Matt 28:9–10), to the two travellers to Emmaus (Luke 24:15), or to the seven fishing by the Sea of Tiberias (John 21:1–4). What a perplexing inconsistency between the various testimonies to these appearances!!

This is an early collection of “witnesses to the resurrection”; Paul wrote to the Corinthians in the mid 50s. But there is no mention of what was important to all four evangelists, writing in later decades: the women at the empty tomb and the role that women played in bearing testimony to the risen one. Is this accidental? or deliberate? Given what we have noted about 1 Corinthians as a whole—and especially what ch.14 reveals about the disorderly behaviour of Corinthian women—we might well wonder, is Paul shaping the received tradition to “fit the context” already at this early stage? It is a tantalising suggestion.

There is a wonderful quote that is pertinent to this issue, which is attributed to Gustav Mahler, the late 19th century Austro—Bohemian composer: “Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.” These words indicate that if tradition stands still, it will run out of momentum and fizzle out of energy. Tradition always needs to be reinvigorated and renewed, in the way that fire sizzles and snaps as it continually changes its shape and form.

And that’s a fine thought for us to have as we consider the resurrection of Jesus. As the Apostles Creed affirms, echoing 1 Cor 15:3–5, “we believe in Jesus Christ … who was crucified, died, and was buried … who rose again from the dead on the third day”. We need to renew and rekindle that tradition, to find fresh ways to understand and proclaim that mysterious happening, which sits at the heart of classic Christian confessions.

I’ve offered my own initial reflections on precisely that task in this blog: