This Sunday the lectionary invites us to revisit the wonderful song of praise that Luke says that the young, pregnant Mary offered (Luke 1:46–55; see https://johntsquires.com/2021/12/07/magnificat-the-god-of-mary-luke-1-is-the-god-of-hannah-1-sam-2-advent-4c/)

This follows soon after the account of how an angel appeared to Mary and informed her of God’s plan for her, a virgin, to be overshadowed by the Holy Spirit, conceive, and bear a child (Luke 1:26-38; see https://johntsquires.com/2020/12/14/advent-four-the-scriptural-resonances-in-the-annunciation-luke-1/)

Of course, Matthew tells a very different version of how this news was conveyed: a scene in which an angel explains Mary’s pregnancy to Joseph, completely omitting any communication with Mary herself (Matthew 1:20–25; see https://johntsquires.com/2019/12/17/now-the-birth-of-jesus-the-messiah-took-place-in-this-way-matthew-1/)

So how did Joseph inform Mary of this news? Perhaps Matthew hints at a very early example of mansplaining?

There is more that we want to know, to fill in the gaps, in the accounts that both evangelists provide. And we are not alone in that desire to know more than what is in these Gospels. From early in the Christian movement, there were people whose curiosity led them to construct narratives which provided “more information” than what the earliest Gospels offer.

We find this, for example, in second century text, the Protoevangelium of James (also known as the Proto-Gospel of James, or the Infancy Gospel of James). This work weaves a long tale, commencing with Joachim and Anna, the parents of Mary, incorporating distinctive versions of the various events reported by both Luke and Matthew in their first two chapters—Zechariah and Elizabeth, Mary and Joseph, the census, Herod and the Magi—and it runs through until the mention of Simeon in the temple (towards the end of Luke 2).

In a later chapter, it describes a test that Mary had to take, when her pregnancy was discovered by the local authorities. The test follows the biblical prescription set out in Numbers 5:11-31, in which “if any man’s wife goes astray and is unfaithful to him … the man shall bring his wife to the priest; and he shall bring the offering required for her”.

After this, the priest shall make a mixture of “holy water that is in an earthen vessel … and some the dust that is on the floor of the tabernacle”, to form “the water of bitterness that brings the curse”. The priest is then instructed to make the woman take the oath of the curse, and say to the woman: “The LORD make you an execration and an oath among your people, when the LORD makes your uterus drop, your womb discharge; now may this water that brings the curse enter your bowels and make your womb discharge, your uterus drop!” The woman is then expected to reply, “Amen. Amen.”

In the Protoevangelium of James, both Mary AND Joseph are made to drink a potion in accordance with this test, to reveal whether they have committed adultery. If they have, it is anticipated that they will develop all sorts of physical ailments, to signal that they have, indeed, sinned by committing adultery. Chapter 16 reads:

16. And the priest said: “Give up the virgin whom you received out of the temple of the Lord.” And Joseph burst into tears. And the priest said: “I will give you to drink of the water of the ordeal of the Lord, and He shall make manifest your sins in in your eyes.” And the priest took the water, and gave Joseph to drink and sent him away to the hill-country; and he returned unhurt.

And he gave to Mary also to drink, and sent her away to the hill-country; and she returned unhurt. And all the people wondered that sin did not appear in them. And the priest said: “If the Lord God has not made manifest your sins, neither do I judge you.” And he sent them away. And Joseph took Mary, and went away to his own house, rejoicing and glorifying the God of Israel.

So Joseph and Mary return unscathed, and their examiner believes their story. They have survived the ordeal of the water of bitterness! But the story of miracles continues. This work provides a detailed description of events surrounding the birth of Jesus.

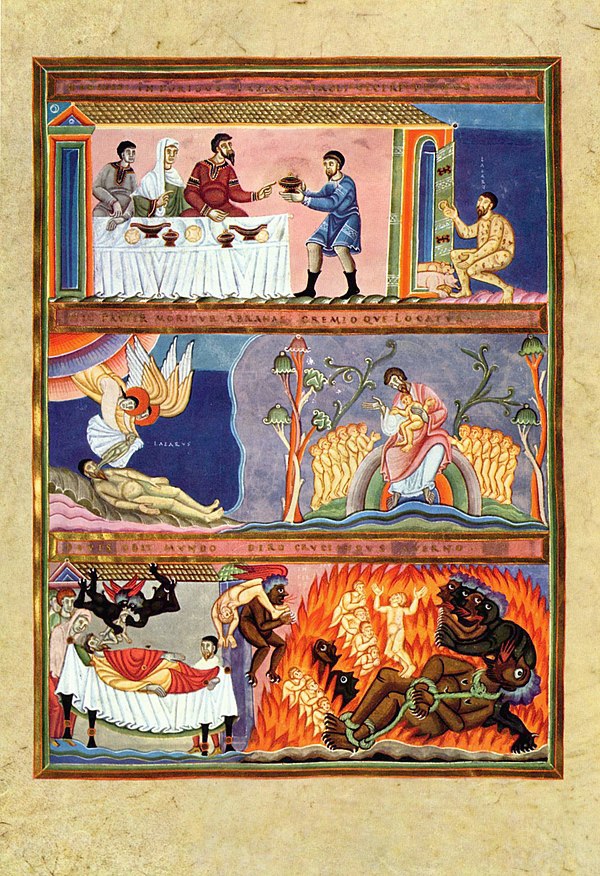

With no proper birthing room, let alone an epidural, one might think Mary had a tough time during labour. Matthew and Luke skip over the birth, mentioning it only off-handedly (Matthew 2:1; Luke 2:6–7), but some Christians were curious about the labour. As opposed to Luke’s account of the new-born Jesus lying in a Jesus manger (2:7), the Protoevangelium of James describes how Mary gives birth in a cave.

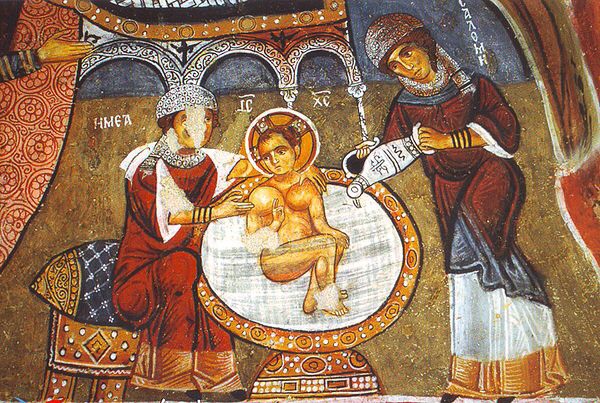

As soon as Mary enters the cave, it shines with bright light—reminiscent of the scene of the Transfiguration in our canonical Gospels. A midwife, arriving too late to help, is shocked when she sees the minutes-old Jesus walking over to Mary and suckling at her breast. Mary is said to have experienced no pain at all during the birth. The midwife then verifies that Mary retained her virginity even after giving birth.

A 12th-century fresco from Cappadocia.

Chapters 19-20 tell of the scene of the birth of the child in the cave.

19. And behold a luminous cloud overshadowed the cave. And the midwife said: “My soul has been magnified this day, because my eyes have seen strange things — because salvation has been brought forth to Israel.”

And immediately the cloud disappeared out of the cave, and a great light shone in the cave, so that the eyes could not bear it. And in a little that light gradually decreased, until the infant appeared, and went and took the breast from His mother Mary. And the midwife cried out, and said: “This is a great day to me, because I have seen this strange sight.”

And the midwife went forth out of the cave, and Salome met her. And she said to her: “Salome, Salome, I have a strange sight to relate to you: a virgin has brought forth — a thing which her nature admits not of.” Then said Salome: “As the Lord my God lives, unless I thrust in my finger, and search the parts, I will not believe that a virgin has brought forth.”

20. And the midwife went in, and said to Mary: “Show yourself; for no small controversy has arisen about you.” And Salome put in her finger, and cried out, and said: “Woe is me for mine iniquity and mine unbelief, because I have tempted the living God; and, behold, my hand is dropping off as if burned with fire.”

Of course, this offers us sooooo much information—too much information! There are intimate personal details, known in so much detail, that are recounted. At one level, it piques the interest and satisfies the curiosity of the human reader. But we should note that this comes from a writer who, according to scholarly consensus, was writing at a later time, many decades after the events reported. How did he have access to such detailed information, so many personal elements, so much later in time? We rightly adopt a scepticism about such a piece of literature. The “hermeneutic of suspicion” is clearly warranted in this instance.

(The author self-identifies as writing very soon after the events recounted: “I James that wrote this history in Jerusalem, a commotion having arisen when Herod died, withdrew myself to the wilderness until the commotion in Jerusalem ceased, glorifying the Lord God, who had given me the gift and the wisdom to write this history.” Nevertheless, contemporary scholars are unanimous in the view that the work was written by a person unknown, at least a century and a half, if not more, after the death of Herod in 4 BCE.)

It is worth noting, also, the way the story is written, throughout all 24 chapters. The book adopts a style that clearly and self-consciously imitates a scriptural way of writing. The author ensures that as many scriptural events and incidents are referred to in this work as is possible. The style is reminiscent of biblical passages which self-consciously evoke earlier writings, as a technique designed to bolster their validity. The method is a standard one, that nestles the later work into the stream of the earlier works. Some key sections of our canonical Gospels clearly adopt this technique—including Luke 1–2 and Matthew 1–2. Perhaps that is part of the reason why they were canonised?

Furthermore, the author, who calls himself James, seems to have enjoyed the tasks of harmonising the infancy narratives of Matthew and Luke, and adding in much more detail than is offered in either of these works. It feels to me that the author is working incredibly hard to establish his credentials as valuable and authoritative—perhaps too hard?

We know that the process of harmonising the Gospels became an industry in later centuries, as church fathers grappled with apparent discrepancies between the Gospels; witness the 2nd century Diatessaron by Tatian, the Gospel of the Ebionites from the same period (which unfortunately we don’t have in a full extant form), the Ammonian Sections, the Eusebian Canons, Augustine’s Harmony of the Gospels, and then a series of manuscripts from late antiquity and the Middle Ages. The Protoevangelium sits in this company, as it works exclusively to harmonise the infancy narratives. It is a later enterprise, from beyond the first century.

I wonder whether, as we lay aside our curiosity to know more, and adopt a rigorously critical approach to this particular text (and others like it, from later centuries, presenting themselves in the mode of earlier documents), we might also consider the value of the “hermeneutics of suspicion” and the historical-critical approach taken, when we read our canonical texts? It seems easier to be critical of works that have not been incorporated into our canon of scripture. Why can we then not take the same approach to the works that have been deemed to be canonical?

You can read the whole text of the Protoevangelium of James at https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0847.htm

Postscript

The Protoevangelium of James provides the earliest assertion of the perpetual virginity of Mary (meaning she continued as a virgin during the birth of Jesus and afterwards). In this it is practically unique in the first four centuries. The only other place this view is expressed is by Origen, in his Commentary on John 1, 4, and also in his Commentary on Matthew 10, 17.

An edited version of the Protoevangelium, along with a set of letters alleged to have been exchanged between the scholar, Jerome, and two Bishops, Comatius and Heliodorus, forms the first part of a seventh or eighth century document entitled The Infancy Gospel of Matthew, also known in antiquity as The Book About the Origin of the Blessed Mary and the Childhood of the Saviour. It is followed by an expanded account of the Flight into Egypt (it is not known on what this is based), and an edited reproduction of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas.

The Infancy Gospel of Matthew, of course, is the basis for developing Catholic traditions about Mary which still hold sway in popular piety. It provides the first known mention that an ox and a donkey were present at the birth of Jesus. The work also helped popularize the image of a very young Mary and relatively old Joseph. We see both of these features in the classic “nativity scene” which was first created by Francis of Assisi.

clearly showing features from the apocryphal tradition.

Salome (far right), ox and ass at the manger from Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew.

Finally, the Infancy Gospel of Matthew tells of how Mary, Joseph, and a two-year-old Jesus are surrounded by dragons. Jesus, unafraid, walks over and stands in front of them. The dragons worship him and then leave in peace. This event is linked to the prophecy of Psalm 148:7: “Praise the Lord from the earth, O dragons and all the places of the abyss.”

On Mary as a virgin in the canonical Gospels, see https://johntsquires.com/2019/12/21/a-young-woman-a-virgin-pregnant-about-to-give-birth-isa-714-in-matt-123/ and https://johntsquires.com/2020/12/22/on-angels-and-virgins-at-christmastime-luke-2/

James McGrath has used this ancient document as the basis for a very creative consideration of “what Jesus learnt” from both his mother and his grandmother, in his fine book, What Jesus Learned from Women. See