Contextualising our Carols: the work of Shirley Erena Murray

Shirley Erena Murray, of Aotearoa New Zealand, has been one of the most prolific and important hymn writers of the 20th century. One of my favourite quotes from her is “I’m despairing of outdated hymns and songs that are irrelevant to contemporary life and the way we live it”. As you may have guessed, I am right on the same wavelength as Shirley Murray!

“I choose to write with liberal intent, persuading people to look again at what the Gospels actually say and what new truths can come out of them”, she said. With over 400 hundred hymns written by her over her life, and many of them published in more than 140 collections across denominations, countries and continents—including Together in Song—she is well-qualified to speak about this. “What has nudged and provoked me”, she continued, “are the people I admire who have gone to the edge in terms of taking the gospels seriously and followed the Jesus principles.”

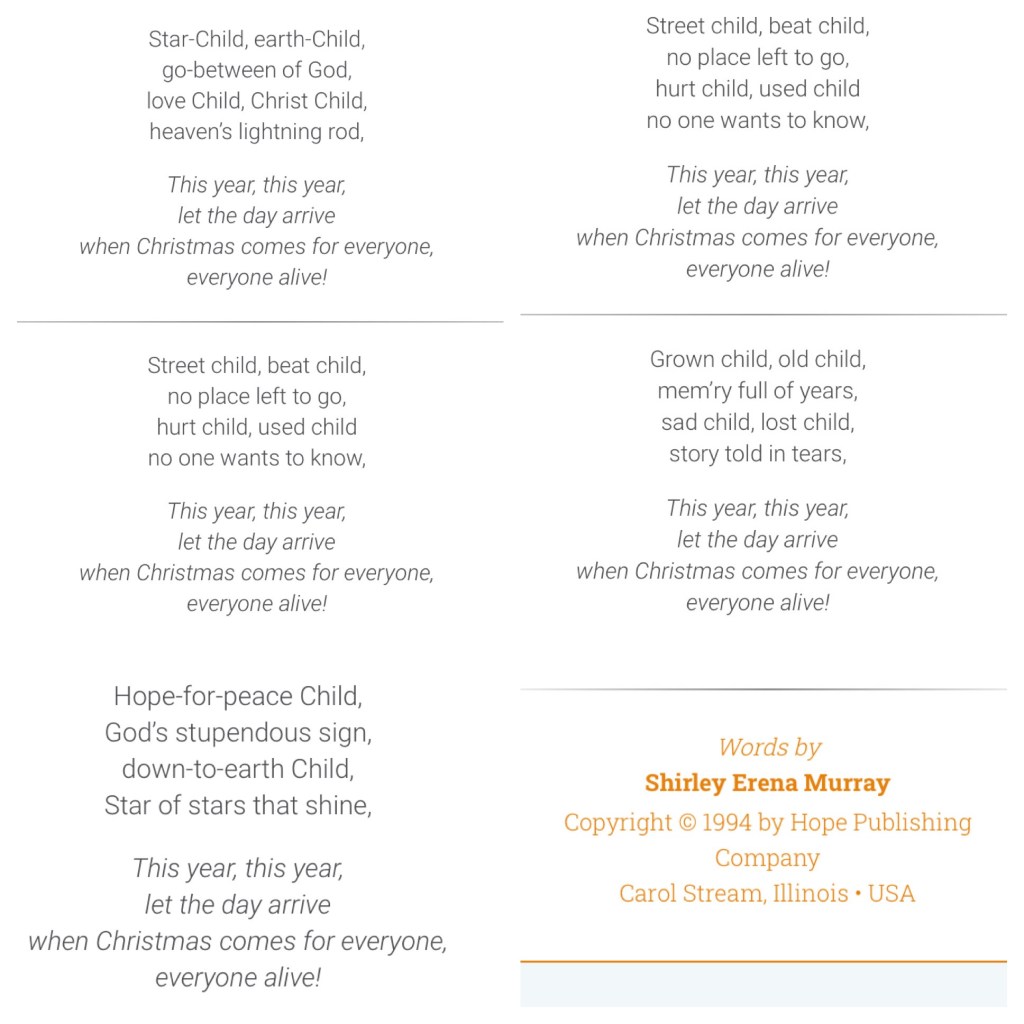

Perhaps her best-known Christmas hymn is surely Star-Child, earth-Child:

See https://musiklus.com/product/star-child/

Another insightful carol reflects the “upside-down” nature of Christmas in the southern hemisphere. It begins:

Carol our Christmas, an upside-down Christmas: /snow is not falling and trees are not bare. / Carol the summer, and welcome the Christ Child, / warm in our sunshine and sweetness of air.

See https://folksong.org.nz/nzchristmas/upside_down_xmas.html

Commenting on how she approaches such seasonal carolling in a 1996 interview, Shirley said: “All our theology in New Zealand is upside down. We don’t have springtime at Easter. Instead, we think of burning leaves and planting bulbs for the spring. We can’t talk about robins and reindeer and snow at Christmas time, which is why I wrote Upside Down Christmas. This explores the images that make sense to us in summertime.” (Peace is Her Song p.137).

Joy Cowley, in her introduction to the 1996 collection that was entitled Carol Our Christmas, wrote: “For this country and its people, the prevailing symbol of the Christmas season is not snow but light. The star that heralds the Christ child in our midst is the sun, and even the sound of its name is symbolic blessing … In this volume of New Zealand carols … not only do the words and the music here reflect Christmas in Aotearoa, they offer us a wide experience of music and rejoicing.” (Peace is Her Song p.115)

In a 2004 interview, Shirley Murray said: “Carols are one of my favourite areas of work, because they are so challenging, not just because I am a southern hemisphere person when Christmas comes. They are the most theologically challenging part of the story for me. Incarnation is much more important than arguing about resurrection; being embodied is more important than talking about where we go hereafter.”

So in “Summer sun or winter skies”, she writes a carol with many of the “classic” carol elements (Christmas, shepherds, angels, silent night, lullabies) but with a potent message for the contemporary world: “silent night a violent night, hawks are in control of a nation’s soul … goodness will outclass the gun, evil has no tooth that can kill the truth”.

See https://www.hopepublishing.com/find-hymns-hw/hw8388_44.aspx

She continued: “Carols have always posed a lot of questions. How do you relate to what might be called the gaiety and festivity of what Christmas is meant to be and how do you say something about the child in the manger? … I have written about 20 carols and every Christmas, I struggle again to deal with humanity and God and this amazing baby. Carols have kept hustling me, annoying me, making me work on them.” (Peace is Her Song p.114)

So in 2013 she published The Christmas Child is a Troublesome Child, containing the insightful words that this child was “as troublesome as the Word that stirred the waters from the deep … who questions given rule, who flouts convention’s pious face … whose vision takes a thorny path whose cross may be our own”.

See https://musiklus.com/product/troublesome-carol/

Commenting on this carol, Murray observed: “The childhood of Jesus … was surely like any other kid’s. Jesus became very annoying to the system. When you remember that, carols cease to be throw-away, jolly songs, and start to dig at you, to make you worry and wonder what God is saying through this. I sometimes introduce imagery from my own country but generally I write songs that will apply to almost anybody wanting to talk about the Jesus person, not just the Jesus baby.” (Peace is Her Song p.114)

I am going to include the words of a wonderful Epiphany hymn that she wrote in tomorrow’s post in this series. But for today, perhaps a novel way to end this exploration of Murray’s Christmas carols is to offer the words of her Lullaby for Judas (2001). In Peace is Her Song, her grandson Alex specifically notes this hymn, and reflects on how his grandmother “wanted to picture the human experience in its highs and lows, humans as fallible beings, with weaknesses and strengths. She dealt with the light and the dark of human experience—she didn’t gloss over things. She had the courage to confront the difficult topics, I find this particularly inspiring, and it is what makes her reputation so great.” (p.167)

The child is sleeping sound whose star is yet to rise.

Like any baby born, an innocent he lies,

this Judas child, a happy child, with laughter in his eyes.

The child can never dream the wonders he will meet:

the hungry filled with bread, the bitter lives made sweet,

the friend, forgiving to the end, who sees his heart’s deceit.

The child is sleeping sound who knows no horoscope:

his kiss that will betray, his hand to grasp, in hope,

the money bag, the silver swag, and then, the knotted rope.

An extensive list of the Christmas carols written by Shirley Murray can be accessed at https://www.hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com/Hymns_and_Carols/Notes_On_Carols/christmastide_carols_of_shi.htm

Unfortunately the hyperlinks no longer appear to be active.

Shirley’s life and contribution to the worldwide church are now told in a biography, Peace is Her Song: The life and legacy of hymn writer Shirley Erena Murray. Written by journalist Anne Manchester, the book draws on rich sources of material, particularly Shirley’s own words as recorded in several audio and video interviews, and published articles.

The book can be ordered directly from New Zealand via the website www.philipgarsidebooks.com or you can order it via Amazon (Kindle $28 or Paperback $60) at https://www.amazon.com.au/Peace-Her-Song-Legacy-Shirley/dp/1991027826