A sermon on Matthew 20:1–16, written and preached by the Rev. Elizabeth Raine

The Gospel of Matthew was the subject of my PhD research, and I so enjoy teaching that Gospel to groups of people, especially when it comes around in the lectionary (as it has this year). And this might well lead you to think that I look forward to being able to share something of my interest in that gospel in weekly sermons.

However, I have found that as much as I like teaching Matthew, I actually don’t like preaching Matthew—at least not the passages that have fallen to my lot in recent months. You may have noticed that in most of the gospel readings we have heard over the few months, there is almost always a line or two about judgment, eternal punishment, and wailing and gnashing of teeth. Last week’s reading was no exception, with the unforgiving slave finding himself not only unforgiven, but also condemned to be tortured.

Matthew is very fond of predicting a harsh judgment and eternal punishment for his enemies. His gospel contains more references to hell and eternal punishment that most of the New Testament put together, with the possible exception of the book of Revelation. He sneaks these references into his material wherever possible, changing his Markan source to reflect his own interests in God’s wrath.

Now while this is interesting to teach, it is not very helpful when trying to construct a sermon that is meant to give food for thought and help folk reflect on their faith. Not all of us want our enemies to be gnashing teeth and wailing in hell. When I teach and research Matthew, I find myself often asking this question of Matthew’s gospel: what are its redeeming features as far as nurturing faith goes?

This is actually tricky to answer. Even last week’s teaching on forgiveness was undermined by the harsh punishment of the slave. And Matthew is actually a grace-free gospel, in that the Greek word for grace, charis, is never used by the author. Many of the stories in Matthew have a pronounced down side. Matthew often includes things such as alienation from family, name-calling, murder, impossible ethical demands and eternal damnation in his gospel.

However, Matthew does have one unique and I think, extraordinary act of redemption in his gospel, apart from Jesus’ death.

I will start with explaining what this is by using this week’s reading. The parable we encounter in this passage (Matt 20:1–16) is unique to Matthew’s Gospel. As such, it may be considered an insight into the special focus of the Gospel, and reflect something of the writer’s understanding of life around him in first century Palestine.

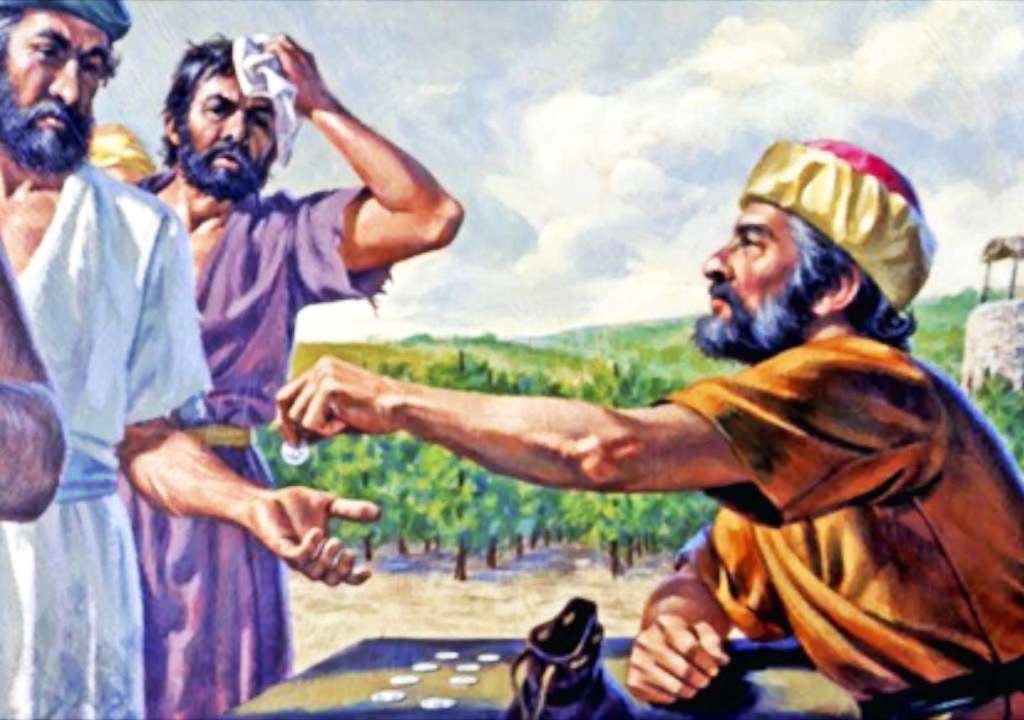

This story of the vineyard workers may well be taken straight from agricultural life in a Palestinian village. Like many of Jesus’ parables, it draws on images and practices familiar to the lifestyle of the crowds who gathered around Jesus to listen to him. Such familiarity would have caught the crowd’s attention and helped them understand the religious teaching that Jesus wanted to convey.

Like many of Jesus’ parables, though, the story has an unexpected twist. Even in first century Palestine, the concept of equal work for equal pay was an established principle. But here we find the vineyard owner paying the same wage to the labourers, regardless of how much or how little time they worked during the day. Such an uneconomical practice must have taken the crowd by surprise. What lord or owner would make such a foolishly generous offer?

The clue is in the last verse of the story, in a saying that Jesus has used a number of times, and one that was no doubt familiar to his disciples and regular followers: “the last shall be first and the first shall be last”.

With this phrase, the vineyard is revealed as the kingdom of heaven, and the owner is, of course, God – the God who is as generous to those who seek his kingdom at the last minute as he is to those who found it much earlier.

The verses which follow after this parable show that it must have been difficult for the disciples to hear, especially James and John! The request of the mother of James and John made it clear that they and the other disciples had given up everything they had to follow Jesus, with the expectation of heavenly reward. Now those who would join the movement later, who have not given up so much or suffered as long, would be greeted by God as equals.

Most scholars think that Matthew may have included this story to defend Jesus’ inclusion of sinners in the kingdom as well as the righteous, though this doesn’t explain why the emphasis is on those who come to the kingdom later. Maybe Jesus meant the story to be understood symbolically, with the ‘last’ being the same as the ‘least’, and thus servanthood and humbleness are being emphasised.

I have another take on this. In a swift segue, I am now jumping into another story in Matthew that does not make it into the lectionary. And that is the story of Judas.

What do we remember Judas for? What is his story? Does anyone remember how Judas died?

All the gospels state that Judas goes to the chief priests and asks for money to betray Jesus. Luke and John both state that Satan entered into Judas. John also calls him a devil and a thief. All the gospels have Judas arrive in the Garden of Gethsemane to betray Jesus with a kiss. It is what happens after this that is unique to Matthew.

Judas, as befitting his actions, meets with an untimely end. There is one version of Judas’ death in Acts: this man acquired a field with the reward of his wickedness; and falling headlong, he burst open in the middle and all his bowels gushed out. This became known to all the residents of Jerusalem, so that the field was called in their language Hakeldama, that is, Field of Blood. (Acts 1:18).

Another less familiar version of Judas’ death is found in the second century church father Papias. Papias obviously had a colourful imagination. A fourth century bishop named Apollonius cites what a second century bishop named Papias apparently claimed about Judas: Judas did not die by hanging, but lived on, having been cut down before choking. And this the Acts of the Apostles makes clear, that falling headlong his middle burst and his bowels poured forth.

Apollonius goes on to say that Papias the disciple of John records this most clearly, saying thus in the fourth of the Exegeses of the Words of the Lord: Judas walked about as an example of godlessness in this world, having been bloated so much in the flesh that he could not go through where a chariot goes easily, indeed not even his swollen head by itself. For the lids of his eyes, they say, were so puffed up that he could not see the light, and his own eyes could not be seen, not even by a physician with optics, such depth had they from the outer apparent surface. And his genitalia appeared more disgusting and greater than all formlessness, and he bore through them from his whole body flowing pus and worms, and to his shame these things alone were forced [out]. And after many tortures and torments, they say, when he had come to his end in his own place, from the place became deserted and uninhabited until now from the stench, but not even to this day can anyone go by that place unless they pinch their nostrils with their hands, so great did the outflow from his body spread out upon the earth.

One of the exercises we do in introduction to New Testament Studies is to examine which, or indeed, any account of the death of Judas could be historical. Most of the students find these two versions to be fiction. But we do have another account in the gospel of Matthew.

Matthew treats Judas differently from the beginning. For a start, only Matthew mentions the sum of 30 pieces of silver being Judas’ fee for the betrayal. The sum of 30 shekels of silver was the value put on the Lord by the corrupt leaders of Israel in the book of Zechariah.

Only in Matthew does Judas ask the question “Is it I, Rabbi?” when Jesus states that one of them will betray him. Just as an aside here, in Matthew’s gospel, Jesus is only called rabbi twice, and both times it is by Judas.

At the moment of the betrayal, only in Matthew does Jesus refer to Judas as ‘friend’, and he also tells him “may that for which you are here be done”. This is rather different to the question of Luke’s Jesus: “Judas, do you betray me with a kiss?” The Jesus of Mark and John says nothing to Judas at this point.

Whilst the account found in Luke—Acts indicates that Judas goes off to enjoy his ill-gotten gains, and is only cut short in this aim by some judicious punishment on God’s part, the story is very different in Matthew.

In a passage unique to this gospel, the Judas of Matthew is overcome with remorse when he sees Jesus is condemned. He repents, returns the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and elders, and states that he has “sinned by betraying innocent blood”. Met with disinterest and no compassion by the priests, Judas throws the money down in the temple, then leaves, to hang himself. The Greek in Matthew leaves us in no doubt as to Judas’ self-inflicted fate, despite Papias’ attempts to resurrect him so he can then unrepent, and go off and buy his field as per the account in Acts.

Judas, through Christian history, has been demonized for his actions. One can see this beginning in the later gospels of Luke and John, who insist that Judas was a sinner possessed by the devil or Satan, and of course in the later Papias, whose Judas is a very caricature of evil. Matthew does not join in this demonisation of Judas. Not only that though, Matthew goes even further, in that Matthew offers to Judas one of the greatest acts of salvation in our New Testament – he actually redeems Judas.

How can you be sure of that?, I hear you cry. Firstly, note that Judas repents. Repent is a word used sparingly in this gospel. It first appears with John the Baptist, he cries to people to ‘repent for the kingdom of heaven draws near”. John also tells them to ‘bear fruit worthy of repentance’. Jesus echoes the cry of ‘Repent, for the kingdom has drawn near’ in the next chapter.

In chapter 11, Jesus upbraids the cities of Chorazin and Bethsaida for not repenting, despite having many miracles carried out in them. In chapter 12, he reminds the unrepentant that the city of Ninevah repented when hearing Jonah’s proclamation about God. Where does Judas’ repentance fit with this?

The depiction of Judas throughout Christian history as infamy embodied has led most exegetes to the conclusion that this repentance in Matthew is merely regret, and not genuine repentance.

I have two things to say to this view. Firstly, it would seem that suicide is a rather drastic reaction to mere regret. Suicide speaks of deep remorse and repentance to me. Secondly, Matthew does not use ‘repent’ unless he means it. In fact, in the parable that follows this one in chapter 22, Matthew uses this very word to describe the actions of the son that initially refused to work in the vineyard, then changed his mind (or repented) and went. Jesus makes the point it is this son who did the will of the father.

So we should assume that Judas’ repentance is genuine. This is underscored by Judas not keeping the money but returning it.

Last of all, we need to consider Judas’ motivation in his act of betrayal. In looking at this, we should note firstly that Jesus goes to his death obedient to the will of God. Judas, therefore, becomes part of enacting the will of God. So the question is raised, “Does Judas have a choice”? I am sure that Matthew doesn’t think so, despite Jesus saying earlier ‘woe to the one who betrays the son of man’. The eventual fate of Judas bears out Jesus words, but does not damn him eternally.

The next surprise is that Jesus calls Judas ‘friend’ at the moment of betrayal, and makes the thoughtful statement “may that for which you are here be done” to Judas, implying some sort of foreordained action.

The knock down argument is the scriptural fulfillment that follows hard on the telling of Judas’ demise, when the priests decide to purchase a field with the money:

Then was fulfilled what had been spoken through the prophet Jeremiah, “And they took the thirty pieces of silver, the price of the one on whom a price had been set, on whom some of the people of Israel had set a price, and they gave them for the potter’s field, as the Lord commanded me.” (Matt 27:9–10)

And Judas’ actions in betraying Jesus for 30 pieces of silver, is from the prophet Zechariah, another scriptural fulfillment allusion to the betrayal and sale of the Lord.

Now Matthew’s God is somewhat wrathful in his judgments, but is always just. If Judas had no choice, how can he then be condemned?

Judas’ suicide resembles that of Ahithophel, the man who had assisted Absalom in his rebellion against King David, and was thus the betrayer of David. Like Judas, Ahithophel hangs himself, yet is still described by many of the rabbis as having entered the world to come, or heaven as this world was known.

Judas not only shows regret and remorse, he repents, and in doing so, makes a confession to the priests of his guilt. He returns his ill-gotten gains. When the priests refuse to take the money, Judas throws it into the temple. When they do not reconsider his crime for the shedding of innocent blood, Judas enacts the appropriate punishment on himself. He seeks to make atonement through his own death.

Christians have always given lip service to the notion that even in the last days of life, true repentance is possible. However, the tradition in regard to Judas has consistently and systematically denied him this.

Not so Matthew. His parable of the workers in the vineyard insists that all who come to the right understanding of Jesus and God, even if it be very late in the day, will be welcome in the kingdom. Surely, in accord with the story he tells, this must include Judas.

Matthew, this grace-free, most judgmental of gospels, is also the gospel that extends the most mercy to one of Christianity’s most hated characters. Whatever Matthew’s exact reasons for his version of events, the parable – and its corollary in the story of Judas – surely must remind us of God’s overwhelming grace, a grace that is inclusive of all who would seek God.