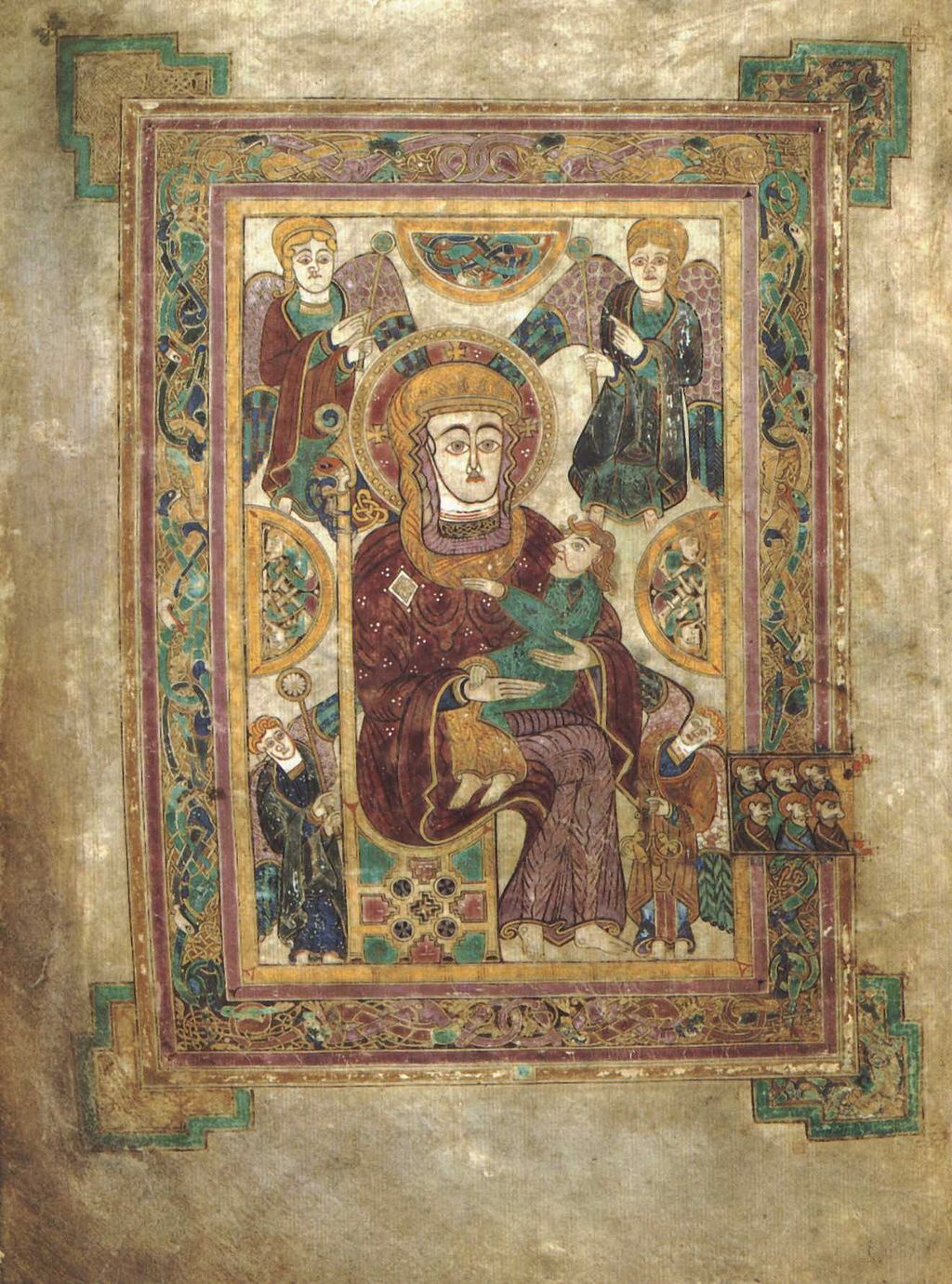

“You will be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth.” (Acts 1:8) So Jesus declares at the start of the second volume of the orderly account of the things being fulfilled among us—the work we know as the book of Acts.

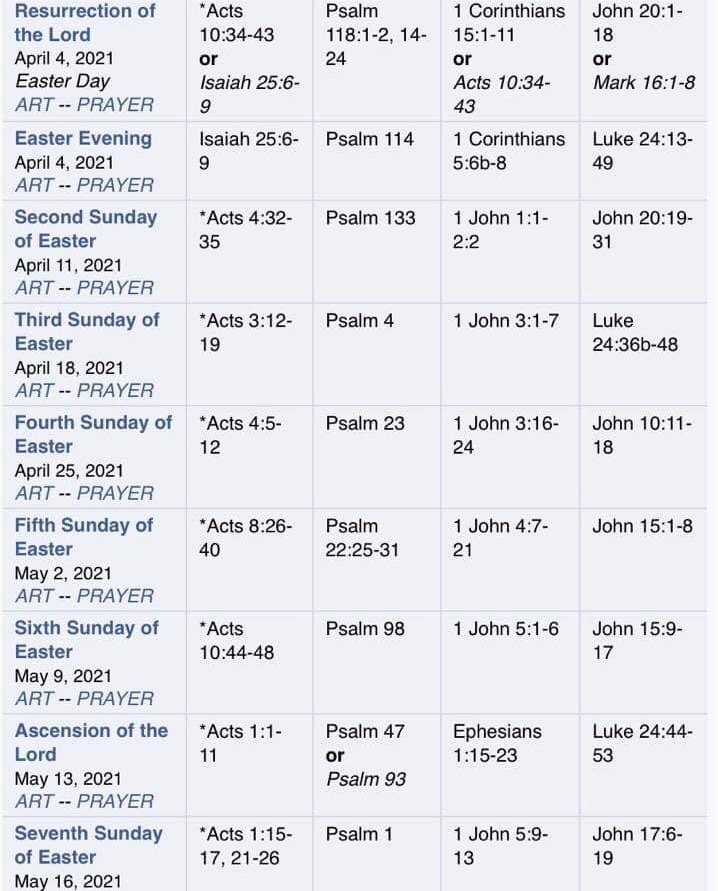

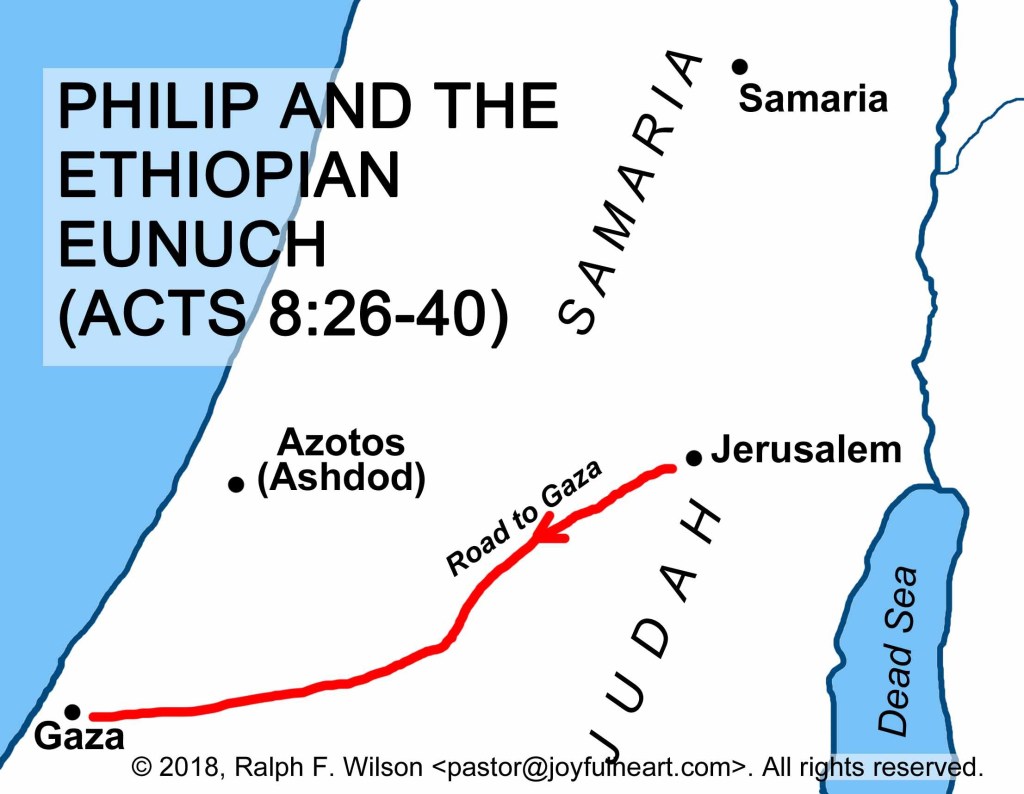

After a series of incidents located in Jerusalem (1:4–8:4), the move into Samaria is recounted in two striking stories. The first (8:5-25) tells of the activities of Philip and the subsequent visit from Peter and John. The second, a conversation between Philip and the Ethiopian (8:26-40), serves to moves the narrative still further away from Judaea, where the events of earlier chapters had been located.

The movement into Samaria begins to play out the progression that Jesus set out in his programmatic words at the head of the volume, telling his followers that they would be empowered as “witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (1:8). Could it be, perhaps, that this encounter with a man from Ethiopia prefigured that eventual move to “the end of the earth”?

On the edge

We certainly are moving to the edges. The scene brings Philip into contact with an Ethiopian: an edgy character, who comes from a location on the edge of the world (in ancient Israelite view), with a gender identity on the edge (a eunuch), in a situation not quite the usual, expected manner (in a chariot travelling away from Jerusalem, not in a home or a settled synagogue or a temple forecourt).

The Israelites regarded Ethiopia as the furthest extent of the earth in the south-westerly direction (Isa 11:11-12). Could this passage, offered as the Acts in Easter reading for this coming Sunday (Easter 5), provide a clear Lukan pointer to “the end of the earth”?

Although the man was a Gentile, he was returning from worship in Jerusalem (8:27); he is probably thus the first of a number of prosecutes who appear in the narrative of Acts (10:2; at 13:50; 16:14; 17:4,17; 18:7). However, he would have been barred from entering the temple precincts because he was a eunuch (Deut 23:1). He was not perfect, and thus not able to present himself directly before the Lord.

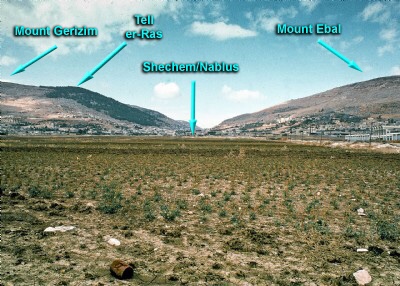

Philip travels south-west towards the coast, on the wilderness road to Gaza, at the urging of “an angel of the Lord” (8:26), a phenomenon already seen in Jerusalem (5:19). His encounter with the Ethiopian is initiated by the spirit (8:29), another phenomenon already abundantly evident in Jerusalem (2:4; 4:8; 4:31; 6:5; 7:55), as also in Samaria (8:17). The encounter is ended by the spirit, when Philip is snatched away immediately after baptising the Ethiopian (8:39). It is a strange and evocative scene.

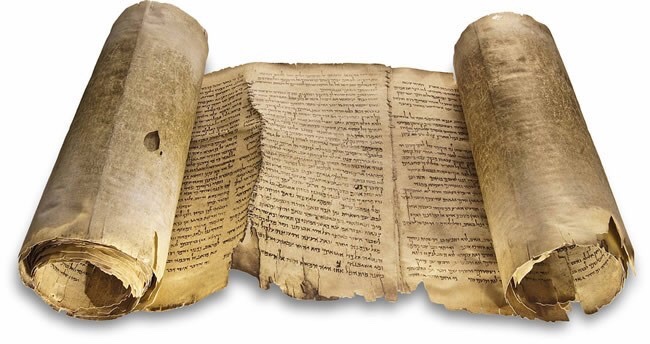

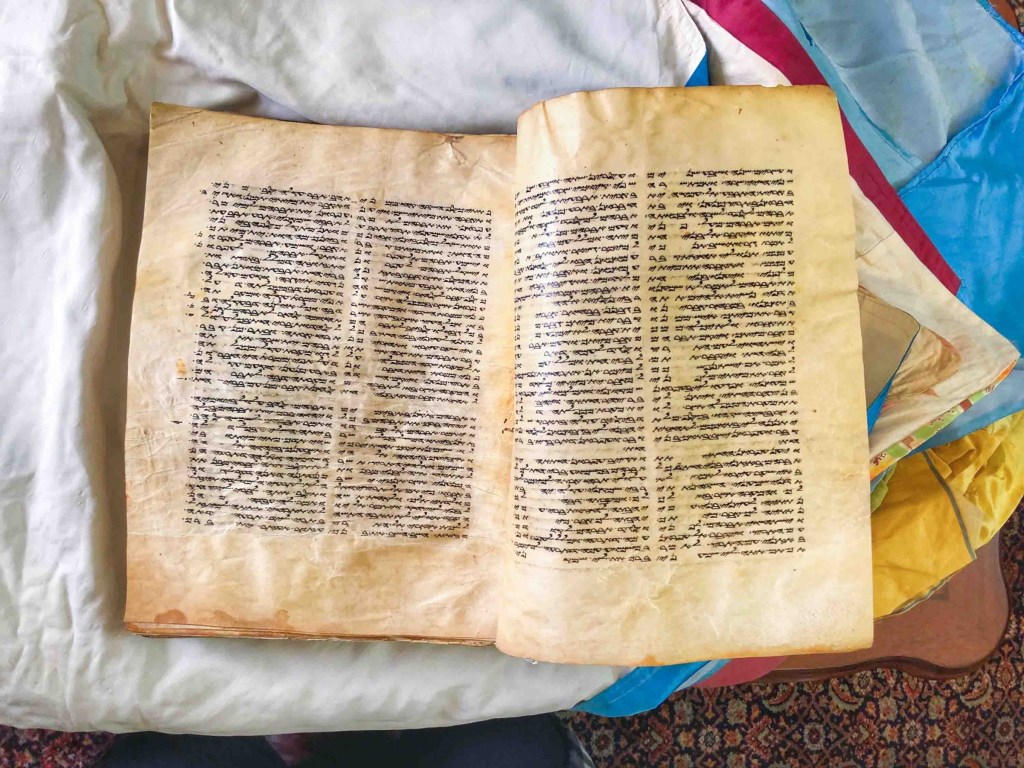

In the Scriptures

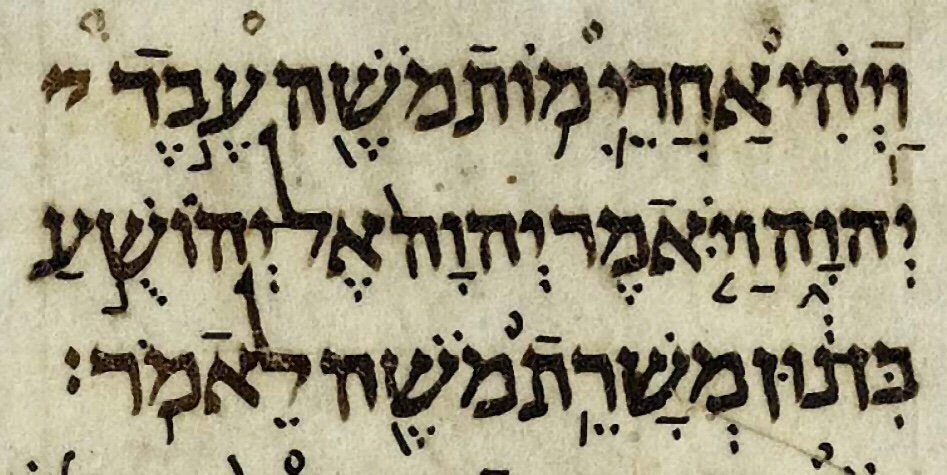

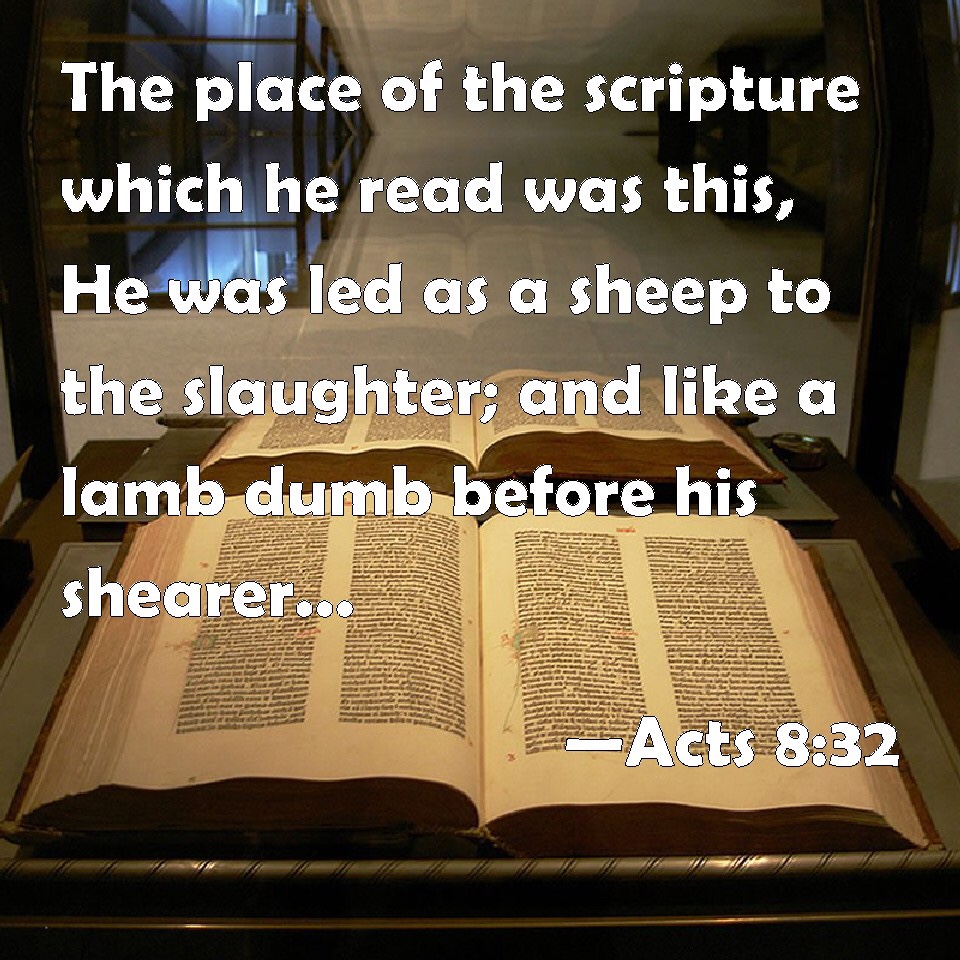

The content of the conversation is given in some detail; of particular interest is the fact that one of the scriptural prophecies which is fulfilled by Jesus is here identified. As the Ethiopian reads of the “lamb led to the slaughter” (Isaiah 53:7-8), Philip explains that this relates to Jesus, whom Philip then preaches to him (8:32-35). Such fulfilment of prophecy has already been introduced in speeches in Jerusalem (2:16-21,25-31,34-35, 3:18, 4:25-26) as another indicator of God’s sovereignty in the events of history.

The particular scriptural passage quoted is part of the fourth “servant song” (Isa 52:13-53:12); various excerpts from this song are interpreted as applying to Jesus by a range of New Testament writers (Matt 8:17; Luke 22:37; John 12:38; Rom 4:25; 5:18-19; 10:16; 15:21; Heb 9:28; 1 Pet 2:21-25).

Into the community

The scene ends with the baptism of the Ethiopian (8:38; see 2:38). Baptism became a means for incorporating people into the community of the followers of Jesus. Baptism of this Ethiopian enabled a person of another nationality to enter into the extending community of messianic believers.

Baptism had been proclaimed as necessary by Peter, on the day of Pentecost (2:38); this appears to link baptism closely with the gift of the Spirit (2;1-4, 17-21). However, there is no reference to the spirit interacting with the Ethiopian in the scene with Philip. The spirit guided Philip in the encounter (8:29, 39)—but appears to have no direct contact with the Ethiopian himself.

Just prior to this incident, the Samaritans who had already “received the word of God” (8:14) were enabled to “receive the holy spirit” through the laying on of hands by the apostles who visited the region (8:15-18). Although the gift of the spirit (8:17) had been separated from baptism (8:12), as also in Ephesus (19:1-7), Luke does not intend this pattern to be read as prescriptive for all situations, as other accounts of baptisms indicate (2:38-41; 8:38; 10:44-48; 19:1-7).

Baptism is accompanied by the laying-on of hands in Ephesus (19:6) and in Samaria (8:15-16), but not with the Ethiopian. The laying-on of hands results in the holy spirit coming upon those in Ephesus (19:6), a link similar to that made in Samaria (8:15-17,19) and Antioch (13:3-4). The gift of the spirit leads to speaking in tongues in Ephesus (19:7), as in Jerusalem (2:4) and Caesarea (10:45-46), but not for the Ethiopian.

In Acts, baptism may come both prior to (2:38-42; 8:14-17) and after (10:44-48; 11:15-17) the gift of the spirit; further, the gift of the spirit is not necessarily linked with baptism (for instance, at 2:1-4 and 4:31). Yet, whilst the time sequence is found in different patterns, the collation of similar elements implies strong continuity with events in Jerusalem, Samaria, Caesarea, and Ephesus. The baptism of the Ethiopian fits, by inference, within that sequence.

Immediately after this baptism, Philip is removed by the spirit of the Lord (8:39). The language of Philip being “snatched away” (8:39) is striking. But unlike those whom Paul describes as being “snatched away” up into heaven (1 Thess 4:17), Philip returns to Caesarea, continuing to preach “good news” (8:40).

His message has already been defined as concerning “the sovereignty of God” (8:12)—a central message in the Lukan works (Luke 7: 29-30; Acts 2:23, 4:28, 5:38, 20,27). The persistent and continuing activity of God in the story that Luke tells, is a strong element throughout the narrative.

This blog is based on a section of my commentary on Acts in the Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, ed. Dunn and Rogerson (Eerdmans, 2003). I have also explored the theme of the plan of God at greater depth in my doctoral research, which was published in 1993 by Cambridge University Press as The plan of God in Luke-Acts (SNTSM 76).