This Sunday the lectionary offers an abundance of gifts: the classic prophetic declaration that God desires us to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God (Micah 6:8); the ringing apostolic affirmation that we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those who are the called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God (1 Cor 1:23-24); and the words which Matthew puts on the lips of Jesus himself, Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven (Matt 5:3).

Those words of Jesus are the first words of blessing in a set of eight blessings (usually known by their Latin name, as Beatitudes), which begin the sermon on the mount (5:3–12)—eight short sayings in which Jesus pronounces blessings on specified groups of people. It is a key section of the book of origins, which provides the Gospel passage this Sunday and on each Sunday throughout the current year.

Often in the Christian church, people marvel at the insight revealed in these sayings of Jesus. And, to be sure, the words offer a deep sense of spirituality, a penetrating insight into the way that God wants human beings to live.

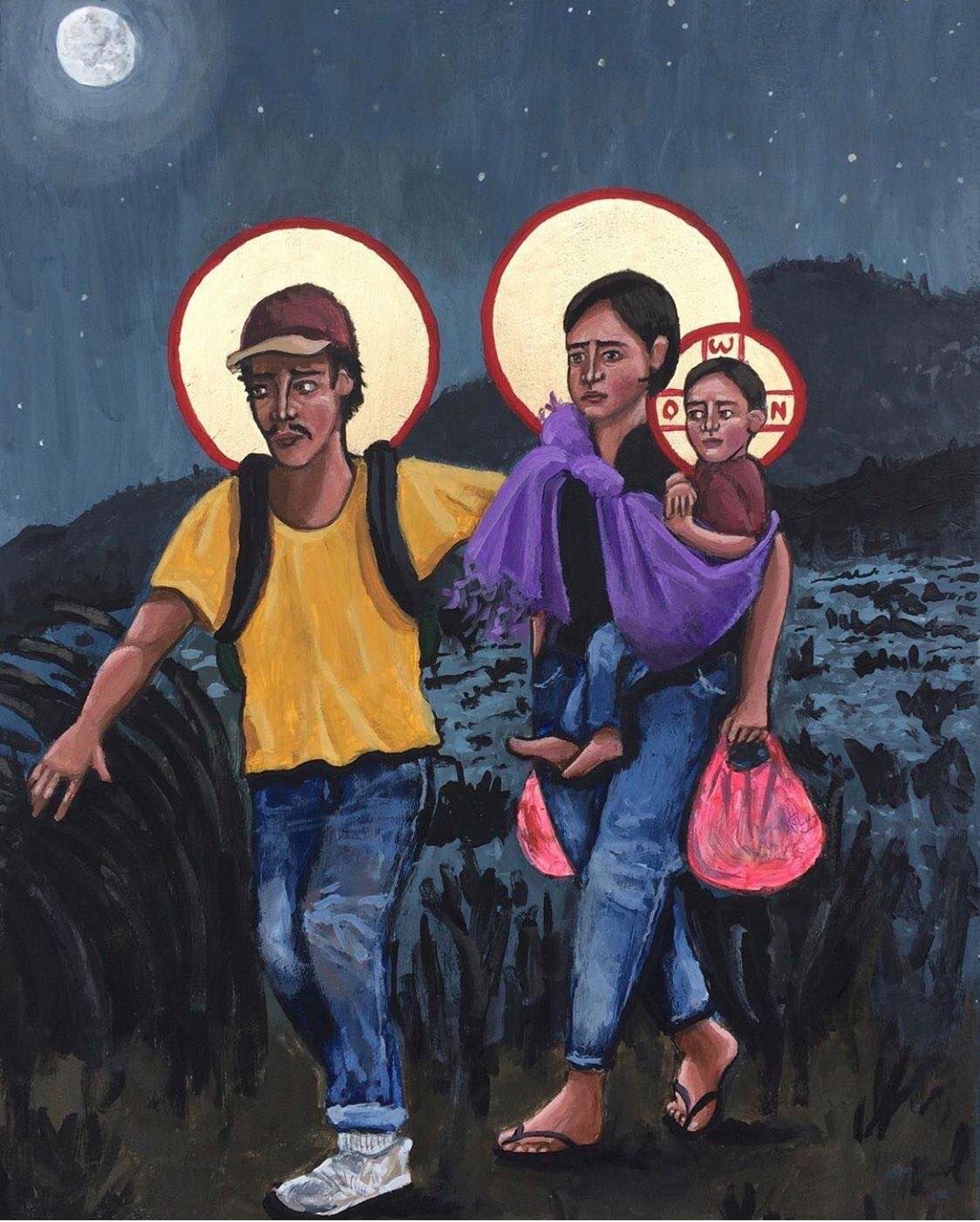

But this collection of sayings is not quite unique and original to Jesus. For Jesus was drawing deeply from within his own Jewish tradition. And the resonances with Hebrew Scriptures are strong and consistent throughout these blessings.

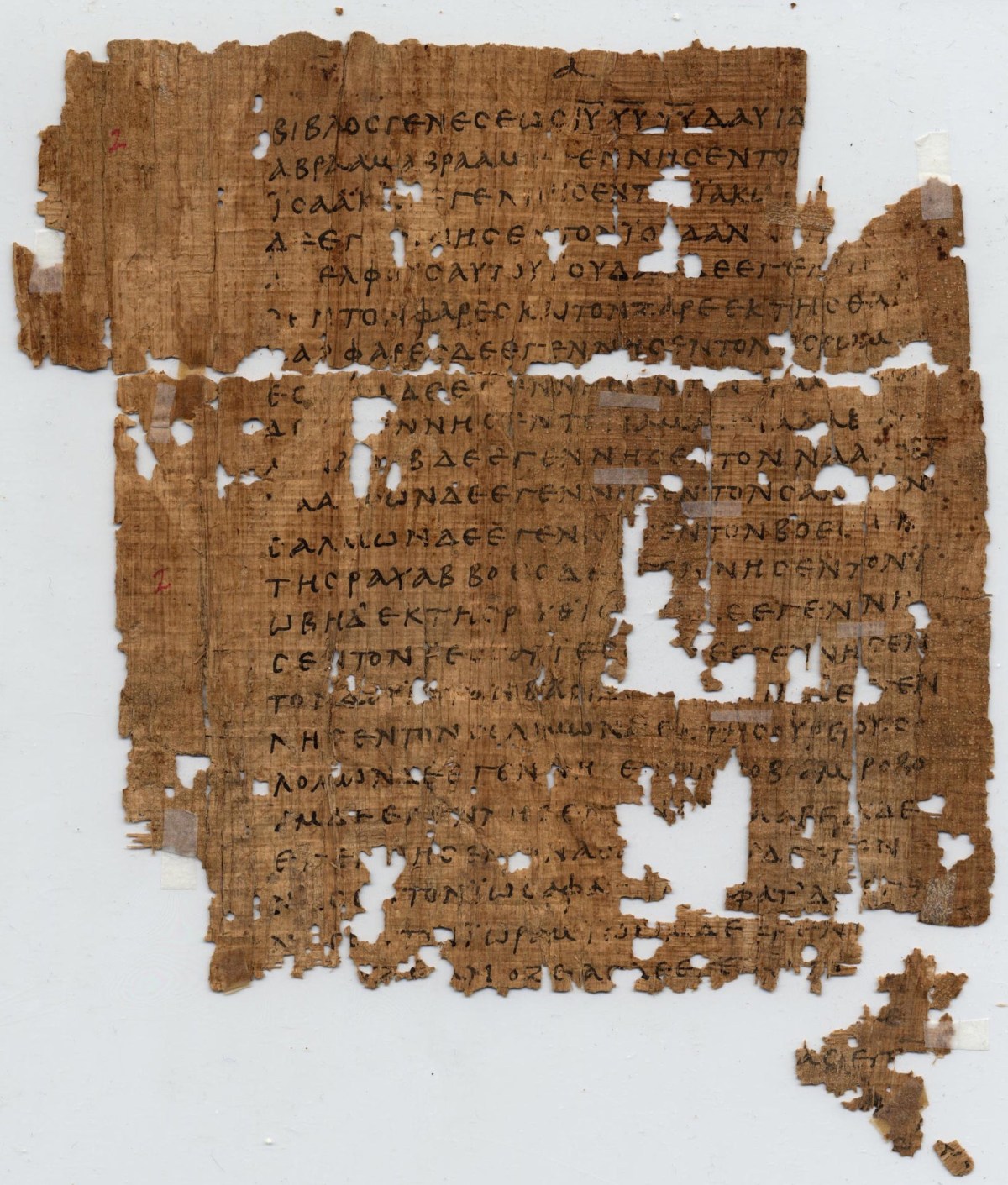

The form is clearly Jewish; there are blessings right throughout Hebrew Scriptures. Blessings are offered in the opening creation narrative (Gen 1:22, 28, 2:3) and throughout the narrative books (Exod 18:10, Deut 28:3-6, Judg 5:24, Ruth 2:19-20, 4:14, 1 Sam 25:32-33, 1 Kings 1:48, 8:15, 8:56, 10:9, 1 Chron 16:36, 29:10, 2 Chron 2:12, 6:4, 9:8, Ezra 7:27, Neh 9:5).

Many psalms offer blessings addressed to God (Pss 28:6, 31:21, 41:13, 66:20, 68:19, 72:19, 89:52, 106:48, 113:2, 118:26, 124:6, 135:21, 144:1) and blessings appear also in some prophetic books (Jer 17:7, Dan 2:20, 3:28, Zech 11:5). Blessings continue on in this form in Jewish traditions, right through to the present day.

The influence of the Hebrew Scriptures can also be clearly seen in the content of these blessings, for they relate traditional Jewish piety regarding the poor, the humble, those who hunger, and those persecuted (as noted below).

A persuasive theory is that Matthew has actually expanded a briefer set of Beatitudes, known to him through early Christian tradition (which may be reflected in Luke 6:20–23), by adding in assorted categories of “the pious” which were known to him from Hebrew Scripture.

Certainly, the effect of placing these sayings, with their traditional Jewish flavour, at the head of the first block of Jesus’ teachings, is to infer that they provide the key to understanding all the subsequent teachings of Jesus in like fashion. Jesus, in Matthew’s opinion, teaches and preaches as one steeped in Hebrew scripture and tradition.

Each one of these beatitudes is based on texts found in the Hebrew Scriptures. In blessing the poor (5:3) and the meek (5:5), Jesus echoes those psalms which speak of those who are poor and meek, who will receive the justice of God and an earth cleansed of evil-doers as their reward (Ps 9:18; 10:1–2, 8–9; 12:5; 14:6; 40:17; 70:5; 72:4, 12; 140:12). Isaiah 61:1 speaks of the good news to the poor; Proverbs 16:19 commends being poor and having a lowly spirit as desirable for those who trust in God.

The blessing offered to the meek, “for they will inherit the earth”, recalls the refrain of one of the psalms (Ps 37:11, 22, 29), whilst the blessing on the merciful evokes the prophetic valuing of mercy (Micah 6:6–8; Hosea 6:5–6).

The blessing of the pure in heart who “will see God” recalls Moses (Exod 3:4; 33:7–11, 12–20; Deut 34:10) as well as words of the psalmist (Ps 17:15; 27:7–9).

Jesus’ blessing of those who hunger and thirst (5:6) similarly evokes earlier biblical blessings on such people (Ps 107:4–9, 33–38; Ezek 34:25–31; Isa 32:1–6; 49:8–12). But in this saying of Jesus, it is specifically those who hunger and thirst for the righteousness, or justice, of God who are blessed. That righteousness, or justice, is a central motif of Hebrew scripture.

Righteousness, or justice, is highlighted in the story of Abraham (Gen 15:1-6, 18:19), is found in many psalms (Pss 5:8, 7:17, 33:5, etc), and recurs regularly in the oracles of various prophets (Amos 5:24, Zeph 2:3, Zech 8:7-8, Mal 4:1-2, Jer 9:24, 33:14-16) as well as many times in Isaiah (Isa 9:7, 11:1-5, 42:6, etc). Jesus draws on this tradition in his blessings, and in other teachings.

The blessings uttered by Jesus upon those who are persecuted (5:10, 11–12) recall the promises of God to such people (Ps 34:15–22), as well as the psalms of the righteous sufferer (Ps 22, 31, 69, 71, etc.). God’s blessing is especially granted in situations of persecution.

The first eight blessings, which all share a tight, succinct form, are framed by the declaration about such people, that theirs is the kingdom of heaven (5:3, 10). The beatitudes thus summarise the criteria for a person to enter the kingdom of heaven—humility, peacemaking, mercy, purity, and a commitment to righteousness or justice in all of life.

******

This blog draws on material in MESSIAH, MOUNTAINS, AND MISSION: an exploration of the Gospel for Year A, by Elizabeth Raine and John Squires (self-published 2012)

See also

https://johntsquires.com/2020/01/23/repentance-for-the-kingdom-matt-4/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/12/11/the-origins-of-jesus-in-the-book-of-origins-matthew-1/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/12/19/descended-from-david-according-to-the-flesh-rom-1/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/11/28/leaving-luke-meeting-matthew/