I am watching the events in Israel with deep sadness and high apprehension. The simmering hotspot of the Middle East has erupted, yet again, in a vicious and worrying way.

I am not a political expert, although I have watched the sequence of events in that region for decades, reading a lot at different times about what has been going on. I don’t really have any connection with Palestinians, but have had quite a lot to do with Jews in Australia over the decades of my ministry, from local contacts with rabbis in neighbouring synagogues through to membership of my church’s national dialogue group with the Jewish People.

I have also been a member of working groups that prepared resources for the national Assembly to consider as they reflected on the relationship that the Uniting Church has with Jewish people, including a paper presented to the 1997 Assembly and then further work which resulted in the Statement on Jews and Judaism which the 2009 Assembly adopted.

That 2009 Statement included an affirmation “that the State of Israel and a Palestinian State each have the right to live side by side in peace and security” (#15), and an encouragement to the members and councils of the UC “to pray and work for a just and lasting peace for both Israelis and Palestinians” (#24). Both of these clauses hold good in the current situation.

Just over a decade ago, the then Assembly President, the Rev. Alistair Macrae, launched a set of resources, Prayer for Peace, which provided practical and prayerful ways of working for peace in the Middel East. He said, “The pursuit of peace is at the core of what it means to be a disciple of Jesus Christ. We echo his words when we share the greeting ‘peace be with you’ with members of our worshipping congregations each week. Jesus expresses the centrality of peacemaking in the Beatitudes; he preaches that peacemakers will be the children of God (Matt 5:9).”

The President continued, “Our commitment to being peacemakers takes us down many paths to peace. It’s our responsibility and imperative to explore all options that could bring about peace in our hearts, our homes, our communities and in our world.”

I think that many of the suggestions in this resource also hold good today, including the Prayer For Peace In Palestine which was provided by a National Working Group set up at that time:

“God of peace, we pray for peace in Palestine, the land where the Prince of Peace walked long ago; Let there be an end to the cycle of violence and vengeance that has prevailed there for so long; Let there be an end to the frequent killing and maiming of people, victims of hate and prejudice; Let there be an end to all political agendas that justify and prolong the conflict. God of peace, hear our prayer.

“Bring justice for all the people of Palestine regardless of race, culture or religion; Sustain the courage and determination of all those who work for peace and keep them strong in the face of threats and persecution; Establish such mutual respect and harmony between Christians and Muslims that they will live and work together for the sake of all. God of peace, hear our prayer.

“Keep our own hearts and minds free from fear and prejudice; Help us to be instruments of your peace where we are. God of peace, hear our prayer.”

That is one thing that we can do, at this time: pray for peace.

There’s another dimension to the current situation that I think bears some consideration. That is the reality of the current political situation, that the lands in the region currently claimed as the modern state of Israel are contested lands, with both Palestinians and Jews laying claim to that area as their ancient ancestral lands.

Whilst there is contention about these claims, there is one matter that I believe merits thoughtful consideration. The claim made by the hard-line right in Israel—reflected in the boundaries of the current state of Israel, including the occupied territories of the West Bank, Gaza, and the Golan Heights—rests on certain biblical texts which, with an ideologically-based orientation, indicate that “God gave this land to the people of Israel”.

In particular, the large extent of land in view under this claim rests on the biblical description of the territory ruled under Solomon, the much-venerated and highly-valorised king of the United Kingdom of Israel around three millennia ago, in a number of texts in the so-called historical narratives of Hebrew Scripture. Whilst those books might look in many ways like historical narratives, we should take care not to assume that contemporary understandings of history can be easily applied to those passages from antiquity.

from Egypt to the Euphrates

In considering these texts, we should begin by noting that the way that Solomon is presented in the Hebrew Scriptures can only be characterised by the term “hyperbolic exaggeration”. It is not an authentic historical depiction of the man; it is a hagiography. Indeed, the actual existence of Solomon in historical reality (in contrast to being a literary character in the Bible) is highly questionable. Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, writing in The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts (Simon and Schuster, 2001), claim that “The glorious epic of the united monarchy was — like the stories of the patriarchs and the sagas of the Exodus and conquest — a brilliant composition that wove together ancient heroic tales and legends into a coherent and persuasive prophecy for the people of Israel in the seventh century BCE.”

See https://www.thenotsoinnocentsabroad.com/blog/did-king-david-and-king-solomon-really-exist

In the story told in the biblical text, King Solomon was said to have “excelled all the kings of the earth in riches and in wisdom. And all the kings of the earth sought the presence of Solomon to hear his wisdom, which God had put into his mind. Every one of [those kings] brought silver and gold, so much, year by year.” (2 Chron 9:22–24). That’s quite a claim!

This wonderfully wise, insightful, discerning man, Solomon—bearing a name derived from the Hebrew for peace, “shalom”—became a powerhouse in the ancient world, we are told. But he did not always live as a “man of peace”. Indeed, the narrative indicates that he used his 4,000 horses and chariots and 12,000 horsemen to good effect; we read that “he ruled over all the kings from the Euphrates to the land of the Philistines and to the border of Egypt.” (2 Chron 9:26; also 1 Ki 4:21). This was the extent of land that had been promised to Abraham (Gen 15:18), and it was more than any other ruler of Israel, before or after him.

So Solomon was remembered as king over the greatest expanse of land claimed by Israel in all of history. Solomon was a warrior. And warrior-kings were powerful, tyrannical in their exercise of power, ruthless in the way that they disposed of rivals for the throne and enemies on the battlefield alike. Think Alexander the Great. Think Charlemagne. Think Genghis Khan. Think William the Conqueror. This is an integral part of the heritage that the story of Solomon bequeathed to Israel: the memory of an aggressive, dominating ruler, lording it over the region. Even though the modern state of Israel doesn’t have a king, this is an image that is being acted out today, in the politics of the region.

Solomon reigned for 40 years—a long, wealthy, successful time—although “forty years” in the biblical narrative should not be understood to be a precise time, but more a statement that this was “a long, extended time”. Solomon exemplifies the model of kingship which survives through into the modern era. We expect kings to rule. We expect them to invade and enforce and dominate, for that is the heritage passed on. (And I won’t comment on Solomon’s marital relationships; I will leave 1 Kings 11:3 to speak for itself!)

This exaggerated, idealised view of things is evident in so many ways in the portrayal of Solomon, who was seen to be filled with “wisdom and knowledge”, and granted “riches, possessions, and honour, such as none of the kings had who were before you, and none after you shall have the like” (2 Chron 1:7–12, especially verses 10 and 12).

It is also worth noting that the large reach of land that Solomon ruled over, even more extensive than the oft-cited phrase “from Dan to Beersheba” (Judg 20:1; 1 Sam 3:20; 2 Sam 3:10; 17:11; 24:2, 15; 1 Ki 4:25; 1 Chron 21:2; 2 Chron 30:5), did not continue past his death. The hagiographical exaggeration of territory under Solomon is not noted in the period after his death. The narrative books that recount the stories of the kingdoms of Israel, in the north, and Judah, in the south, in the centuries after Solomon, indicate that the scope of those kingdoms was more constrained.

In the light of this, I don’t think it is responsible to lay claim to the whole, extended territory of the land, from the biblical passages noted, as the scope for the modern state of Israel which was created in 1948. I therefore have sympathy for Palestinians who have lived on the land for thousands of years prior to 1948, as they understand this to be their ancestral land.

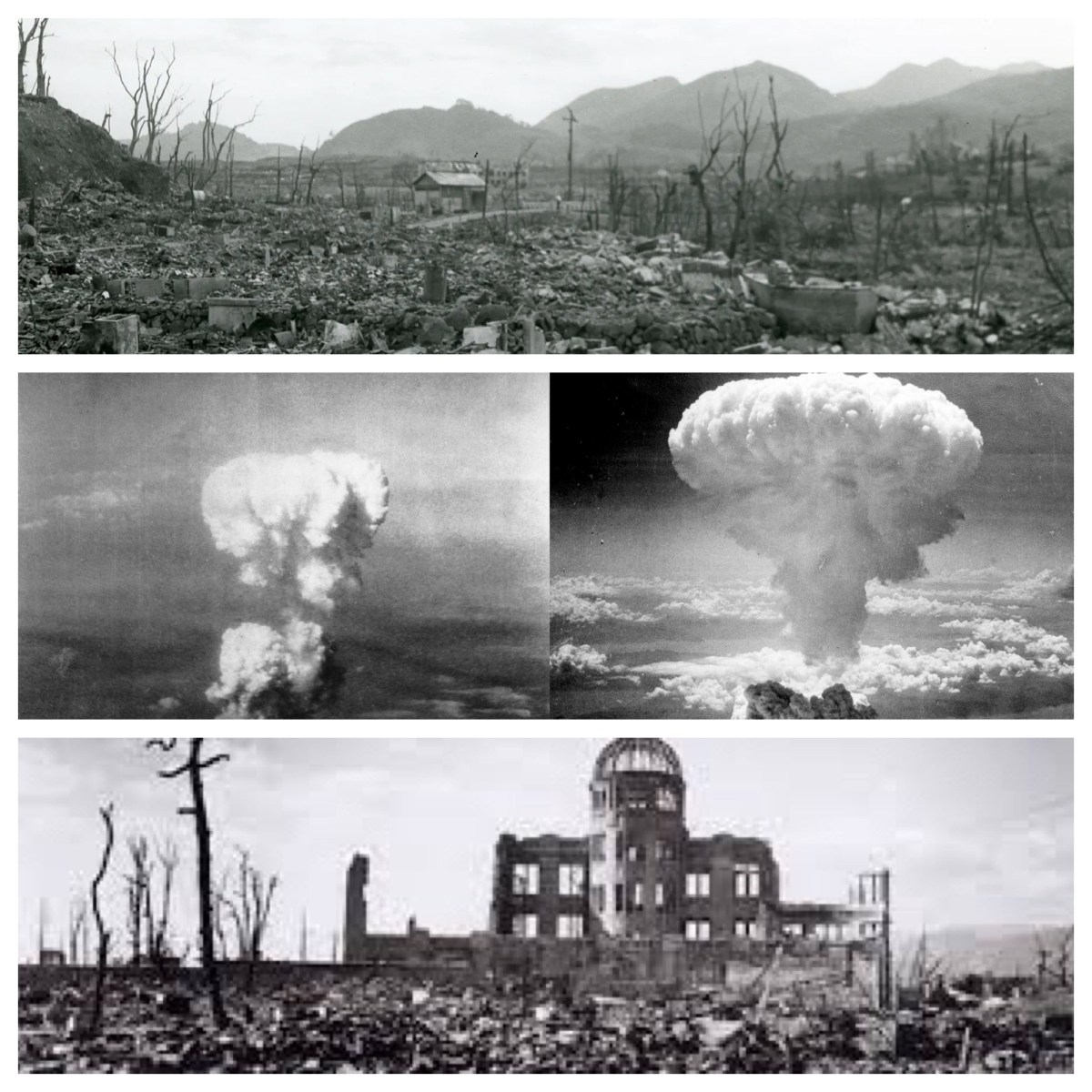

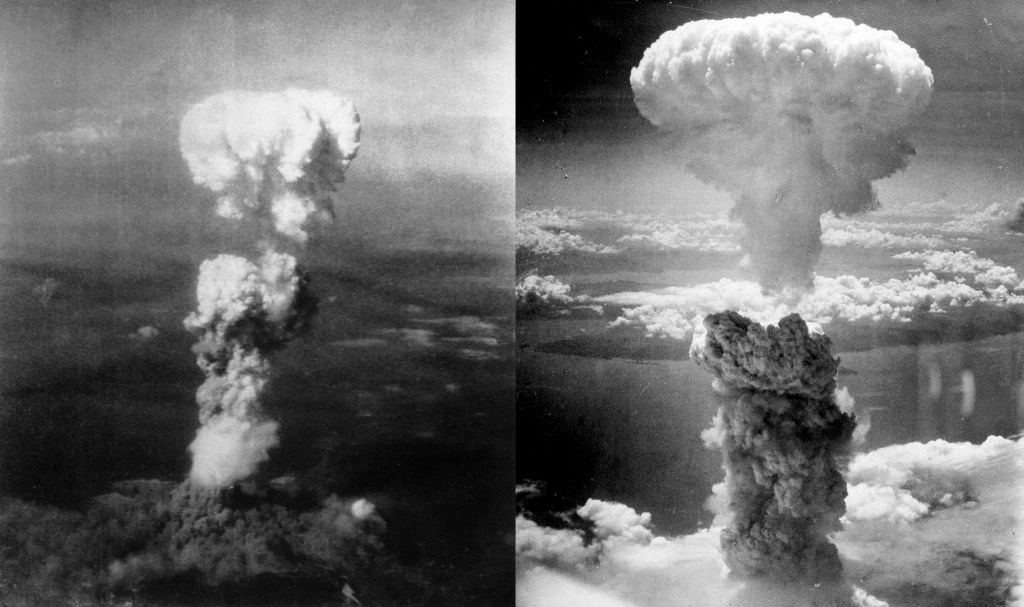

I also have sympathy for Jews, both those living in the land of Israel today, as well as those living in diaspora, for whom the land of Israel has a powerful symbolic significance—especially since the Shoah of 1933—1945 and the terrible genocide perpetrated by the Nazis against Jews in so many countries during that period. Granting them land in the area where their ancestors long ago had lived, a homeland that gives them security in the modern world, is important and necessary.

That said, I don’t agree that Palestinians should take matters into their own hands to seek vengeance against people in Israel in the way that they have done, once again, in recent days. In the same manner, nor do I think that the Israeli forces should respond in the aggressive and violent manner that they have done, once again, in recent days. Too many people are dying and being injured, making any possible progress towards peace with justice even more difficult each day.

We need to seek once more the peace of these peoples. And we need to find that peace on the basis of justice. Neither terrorist attacks nor military crackdowns will achieve this. They will simply exacerbate a dangerous situation.

“Depart from evil, and do good; seek peace, and pursue it.” (Psalm 34:14). “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.” (Matt 5:9). “Justice, and only justice, you shall pursue, so that you may live and occupy the land that the Lord your God is giving you.” (Deut 16:20). “… the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faith. It is these you ought to have practiced …” (Mat 23:23).