This week I am taking leave of my consideration of New Testament passages in the lectionary, to turn to the Hebrew Scripture passage offered by the Revised Common Lectionary: 1 Kings 8.

If you have been following the Old Testament readings offered by the lectionary since Pentecost, you will know we have encountered some fascinating characters. We started way back in May with Hannah, mother of Samuel, offering her prayer of thanks (1 Sam 2).

We saw the adult Samuel, arguing with the people of Israel about whether they should have a king (1 Sam 8). Not everyone was supportive of the idea.

The first king of Israel was Saul; the lectionary offered us the passage where David was chosen as the successor of Saul—the young shepherd who “was ruddy, and had beautiful eyes, and was handsome” (1 Sam 16). Then came the account of David’s encounter with the giant from Gath, the Philistine named Goliath (1 Sam 17), and the telling of David’s love for Jonathan (2 Sam 1). After the death of Saul, the tribes gathered at Hebron, to make a covenant together supporting David as the new king (2 Sam 5).

The following week we had the story of Michal, daughter of Saul, looking out of the window, watching King David leaping and dancing before the ark, dressed only, we are told, in a linen ephod (2 Sam 6).

The ephod is basically a very loose fitting outer garment; given that David was leaping and dancing, we can only surmise that it left little, if anything, to the imagination of onlookers, as it flapped and swirled.

And then, in a dramatic change of mood, we heard Nathan receiving the word of the Lord instructing David to build a house—a temple, no less (2 Sam 7).

The following Sunday provided another insight into the character of David—not only was he a scantily-clad dancer, but an adulterer and murderer as well, as we learn in the well-known story that involves Uriah, his wife Bathsheba, and the king’s officer Joab (2 Sam 11).

This was followed by the gory account of the death of Absalom, the third of David’s 21 children (yes, that’s correct: from his eight wives and ten concubines, David bore at least 21 children!)

Poor long-haired Absalom was murdered after his hair got caught in the branches of an oak tree, and he was left swinging, until ten of the king’s soldiers butchered him. And all of this took place after a battle which was marked by the slaughter of 20,000 Israelites (2 Sam 18).

David, we are told, was grief-stricken. “O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom!”, we are told he lamented. “Would I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!” That is a sardonic reflection, however, on the faux-love of David for his estranged son and his faux-grief on Absalom’s death.

All of these stories reveal to us the character of the leaders in Israel. All of these stories have featured in our lectionary over the last three months—have a look at what has been offered and read those stories, I encourage you. Leaders are human, after all, we find in these stories, and life in those days was tough, rugged, challenging.

The leaders whom we encounter in these stories are devious, unscrupulous, scheming, manipulative, emotional, hard-headed, self-serving, and deeply flawed. All of this. From these ancient texts—as if we didn’t already know this from our own observations of leaders in our own situation!

Which brings us, through these sagas of violence, conflict, betrayal, and drama, to Solomon, son of David, installed as king of Israel after the death of his father (1 Kings 2). God made a promise to Solomon: “I give you a wise and discerning mind; no one like you has been before you and no one like you shall arise after you” (1 Kings 3:12).

*****

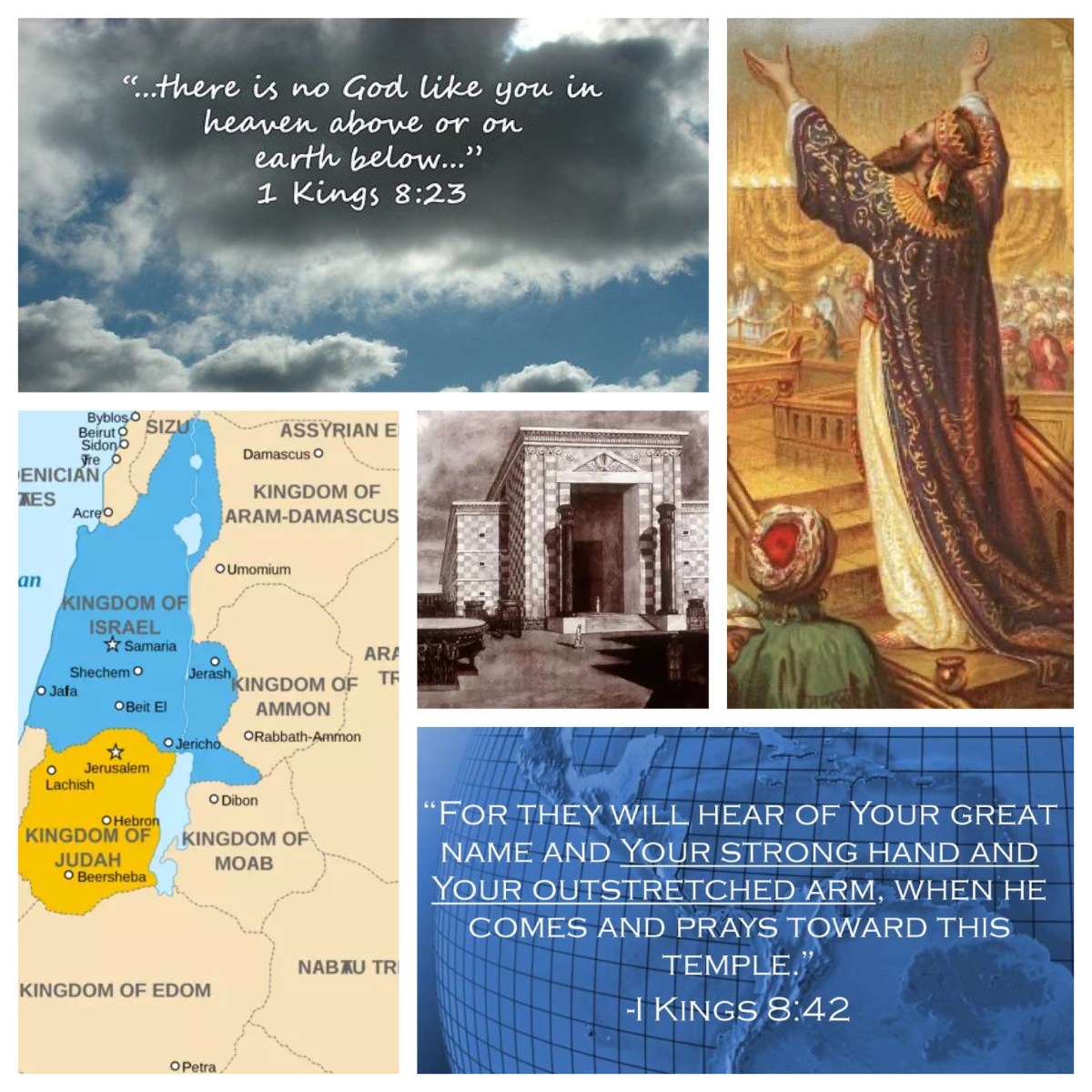

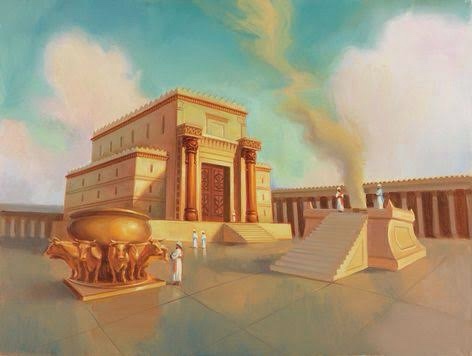

Then we come to the passage set for this coming Sunday, where all the stops are pulled out, as Solomon gathers people for the opening of the Temple (1 Kings 8).

This journey through the narratives of the Hebrew Scriptures reaches it climactic point in this passage, where the greatest king of Israel, Solomon, prays to dedicate the grand religious building, the Temple, on the top of the highest hill in Jerusalem, the capital city of the kingdom at the point of its greatest influence and power. (The readings in following weeks will move into the literature attributed to and inspired by Solomon, the wisdom literature.)

So, we hear the account of this moment of dedication: “Then Solomon assembled the elders of Israel and all the heads of the tribes, the leaders of the ancestral houses of the Israelites, before King Solomon in Jerusalem, to bring up the ark of the covenant of the LORD out of the city of David, which is Zion. Then the priests brought the ark of the covenant of the LORD to its place, in the inner sanctuary of the house, in the most holy place, underneath the wings of the cherub. And when the priests came out of the holy place, a cloud filled the house of the LORD.” (1 Kings 8:1–10).

Man, this is serious stuff: heavy, important, serious. The king. All the elders. The heads of each of the 12 tribes. And the priests, with the ark of the covenant. All assembled at the place where Solomon, king in all his majesty and power, had arranged for a temple to be built. “Then Solomon stood before the altar of the LORD in the presence of all the assembly of Israel, and spread out his hands to heaven” (1 Kings 8:22), and prays a long prayer of blessing for the new edifice.

Now, Solomon, I am sure you are thinking, is remembered as the wise one. “The wisdom of Solomon”, we say. Jesus relates how “the Queen of the south [the Queen of Sheba] came from the ends of the earth to hear the wisdom of Solomon” (Matt 12:42).

In 2 Chronicles 1, God says to Solomon, “because you have asked for wisdom and knowledge for yourself … wisdom and knowledge are granted to you. I will also give you riches, possessions, and honor, such as none of the kings had who were before you, and none after you shall have the like” (2 Chron 1:11–12).

And later, King Solomon is said to have “excelled all the kings of the earth in riches and in wisdom. And all the kings of the earth sought the presence of Solomon to hear his wisdom, which God had put into his mind. Every one of [those kings] brought his present, articles of silver and of gold, garments, myrrh, spices, horses, and mules, so much year by year.” (2 Chron 9:22–24).

This wonderfully wise, insightful, discerning man, Solomon—bearing a name derived from the Hebrew for peace, “shalom”—became a powerhouse in the ancient world. But he did not always live as a man of peace. “Solomon”, the text continues, “had 4,000 stalls for horses and chariots, and 12,000 horsemen, whom he stationed in the chariot cities and with the king in Jerusalem.” (2 Chron 9:25). Solomon had amassed a great army, exercising great power, imposing his rule across the region.

And Solomon, the tenth son of David, the second child of Bathsheba, came to the throne by devious means. It was Adonijah, son of David’s fifth wife Haggith, who sought to succeed his father on his death; Solomon, however, had Adonijah murdered, as well as dispatching the henchmen of Adonijah—Joab the general, who was executed, and Abiathar the priest, who was murdered. This paved the way for Solomon to succeed to the throne. He did not come with clean hands.

But he became a powerful ruler. More is said of Solomon: “he ruled over all the kings from the Euphrates to the land of the Philistines and to the border of Egypt.” (2 Chron 9:26). Solomon was remembered as king over the greatest expanse of land claimed by Israel in all of history. That’s a claim that is still held by the hardest of fundamentalist right-wing Israelis in the modern state of Israel today—claiming that God gave all this land to Israel under Solomon, and that is the extent of the land that should be under the control of the government of modern Israel. Which is not going to happen, given the realities of Middle Eastern politics on our times.

And we see the utilisation of this power by Solomon, the man of peace, in the Chronicler’s comment that “the king made silver as common in Jerusalem as stone, and he made cedar as plentiful as the sycamore of the Shephelah; and horses were imported for Solomon from Egypt and from all lands.” (2 Chron 9:27–28).

So Solomon was a warrior. And warrior-kings were powerful, tyrannical in their exercise of power, ruthless in the way that they disposed of rivals for the throne and enemies on the battlefield alike. Think Alexander the Great. Think Charlemagne. Think Genghis Khan. Think William the Conqueror. Solomon reigned for 40 years—a long, wealthy successful time.

*****

Yet in the passage set for this Sunday, Solomon appears not as a powerful king. Rather, he is a humble person of faith. He stands before all the people, raises his arms, and prays to the God who is to be worshipped in the Temple that he had erected. He is a person of faith, in the presence of his God, expressing his faith, exuding his piety.

Now, the prayer of Solomon goes for thirty solid verses; there are eight different sections in this prayer. The lectionary has mercy on us this Sunday; we are offered just two of those sections, eleven of the thirty verses. We have heard the shortened version! In these two sections of this prayer, Solomon identifies two important features of the newly-erected Temple. The first is that the fundamental reason for erecting this building is to provide a focal point, where people of faith can gather to pray to God (1 Ki 8:23–30).

Perhaps we may be used to hearing about the Temple in Jerusalem in fairly negative terms. Jesus cleared the Temple of the money changers and dove sellers who were exploring the people. He predicted the destruction of the Temple during the cataclysmic last days. For centuries, people from all over Israel were required to bring their sacrifices to the priests in the Temple, to offer up the firstborn of their animals and the firstfruits of their harvest. The Temple cult was a harsh, primitive religious duty, imposing hardships on the people. The priests, the elites who ran the Temple, lived well off the benefits of all of these offerings.

I could offer you a counter argument to each of these criticisms; but today I simply want to note that Solomon, in his prayer of dedication, makes it clear that the fundamental purpose of the Temple was to provide a house of prayer, a place where the people of God could gather, knowing that they were in the presence of God, knowing that the prayers that they offer would be heard by God and would lead to God’s offering of grace, forgiving them for their inadequacies and failures.

The Temple was to be a place of piety for the people. It was to foster the sense of connection with God. It was to deepen the life of faith of the people. It was to strengthen their covenant relationship with the Lord God.

All of which can be said for us, today, about the building that we come to each Sunday, to worship. The church—this church—is a place of piety for us, the people of God. It is to foster the sense of connection with God. It is to deepen the life of faith of each of us, the people of God. It is to strengthen our covenant relationship with the Lord God through the new covenant offered in grace by Jesus. That’s what the church—this church, your church—is to be.

So we read in the first part of Solomon’s Temple prayer. For the people of ancient Israel, standing in the shadow of this wonderful new building, the prayer might encourage a strong sense of self identity, blessed to be part of the people of God. Of course, it could also develop narrow nationalism, a jingoistic praising of the greatness of Israel, extolling their identity as the chosen nation, the holy people, the elect of God.

The Temple invited the people of God to meet the God of the people, to pray, to sing, to offer signs of gratitude and bring pleas and petitions—in short, to keep the covenant, to show that they are keeping the covenant, to be satisfied that they are keeping the covenant, as they worship. It had a strong, positive purpose for the people.

But that is not where the prayer ends. The second key element of Solomon’s prayer that the lectionary offers us today (1 Ki 8:41–43) is striking. It also relates to prayer. But it is not the prayer of the people of God, covenant partners with the Lord God. It is about the prayer of “a foreigner, who is not of your people Israel, [who] comes from a distant land because of your name”. This is a striking and dramatic element to include in this dedication prayer before all the people.

Solomon prays to God, imploring God to “hear in heaven your dwelling place and do according to all for which the foreigner calls to you, in order that all the peoples of the earth may know your name and fear you, as do your people Israel, and that they may know that this house that I have built is called by your name.”

Now that is an incredible prayer for the King of Israel to pray! It reflects an openness to the world beyond the nation, an engagement with the wider geopolitical and social relatives of the world at that time. Solomon was not an isolationist. He was not inward focussed on his nation. He had an outwards orientation. He did not want the Temple to foster a holy huddle, shut off from the world. He had other intentions. He wanted the Temple to be a holy place, open to people from across the region, from far beyond the territory of Israel—a gathering place for all the peoples.

That was the vision that Solomon set forth for his people. That was not always the way that the Temple actually did function, we know. But that was the foundational vision—articulated by Solomon, remembered by the scribes, included in the narrative account of the kings, placed in a strategic position at the opening and dedication of the Temple. It is a vision which speaks, both to the people of Israel, but also to people of faith today, in the 21st century world.

*****

On the temple of Solomon, see https://www.bibleodyssey.org/en/places/main-articles/first-temple