“Restore us, O God; let your face shine, that we may be saved.” So pleads the psalmist, in a psalm that is offered by the lectionary this coming Sunday, Advent 4. The verses chosen (Psalm 80:1–7, 17–19) contain a plea to God, to act in defence of Israel at a time of deep distress. Perhaps this psalm is chosen for this particular Sunday, a week before Christmas, because it refers to “the one at your right hand, the one whom you made strong for yourself” (80:17).

The section of the psalm that is omitted by the lectionary recounts the story of Israel, using the familiar image of a vine (80:8–10) which grew and spread (80:11), but now is ravaged by passers-by (80:12–13), before lamenting the destruction that has taken place amongst the people (80:14–16). The setting seems clearly to reflect the experience of exile in Babylon, after the devastation of the city of Jerusalem by the Babylonian army.

In this psalm, the writer prays for God to act. However, this is not just a single prayer; rather, the writer pleads with God to restore Israel to her former glory. “Restore us” is the persistent plea (80:3, 7, 19), along with calls to “give ear” (80:1), “stir up your might” (80:2), “turn again” (80:14), “come to save us” (80:2), and “give us life” (80:18).

This recurring refrain of petitions is accompanied by the request for God to “let your face shine” (80:3, 7, 19); the prayers accumulate in intensity, reflected in the wording that builds throughout the psalm: “restore us, O God” (80:3); “restore us, O God of hosts” (80:7); “turn again, O God of hosts” (80:14); “restore us, O LORD God of hosts” (80:19).

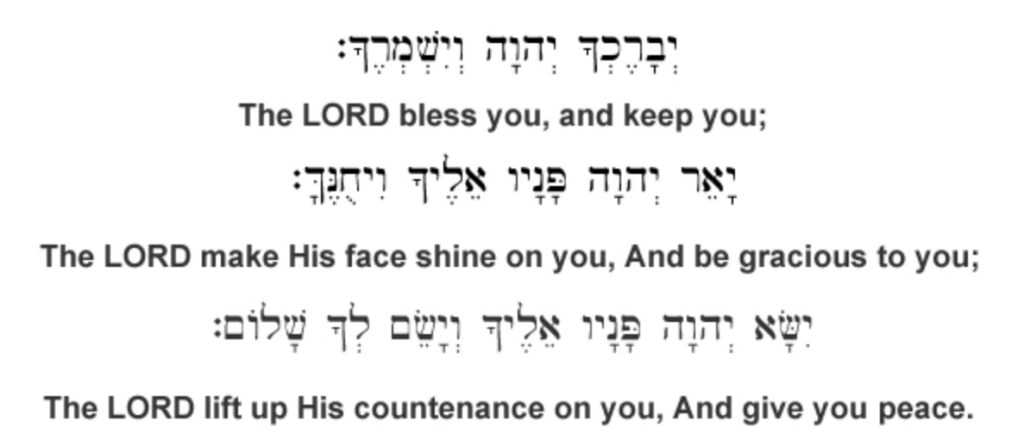

The request for God to let God’s face shine reflects the ancient priestly blessing recorded in Num 6:24–26: “The LORD bless you and keep you; the LORD make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you; the LORD lift up his countenance upon you, and give you peace.”

In this three-line prayer, the second line includes the phrase, “the LORD make his face to shine upon you”. The simple parallelism in this blessing indicates that for God to “make his face shine” (v.25) is equivalent to blessing (v.24) and lifting up his countenance (v.26). The second verb in each phrase is, likewise, in parallel: the psalmist asks God to keep (v.24), be gracious (v.25), and grant peace (v.26). These words offer a prayer seeking God’s gracious presence for the people of Israel.

The face of God was a matter of some significance in the ancestral story of Jacob, who becomes Israel. Estranged for decades from his twin, Esau, when they meet up again, Jacob has just spent the night wrestling with a man (Gen 32:22–32). Jacob’s hip is struck, and he walks with a limp; yet he describes the place where this happened as Peniel, “the face of God”, and characterises the encounter as a time when “I have seen God face to face, and yet my life is preserved” (32:30). To see God face-to-face was a rare and intense experience. Jacob was, indeed, blessed.

When Esau then appears and informs Jacob that he now accepts that the birthright which Jacob stole years ago from Esau should rightly remain with him (33:9), Jacob marvels at the favour which Esau shows him, saying, “truly to see your face is like seeing the face of God—since you have received me with such favour” (33:10). God’s face, evident in Esau, is a face that bestows grace and favour.

So the Psalmist sings, “My soul thirsts for God, for the living God. When shall I come and behold the face of God?” (Ps 42:2). And after the incident involving the idolatry of the golden bull (Exod 32:1–35), Moses yearns to know that he has found favour with God: “if I have found favour in your sight”, he prays, “show me your ways, so that I may know you and find favour in your sight” (33:13). God promises that “my presence will go with you, and I will give you rest” (33:14), but Moses presses his case: “show me your glory, I pray” (33:18).

God holds fast, saying that “I will make all my goodness pass before you, and will proclaim before you the name, ‘The LORD’; and I will be gracious to whom I will be gracious, and will show mercy on whom I will show mercy” (33:19), but then stops short of full self-revelation, declaring, “you cannot see my face; for no one shall see me and live” (33:20). Moses is granted a view of God’s “back”, but is not able to see the face of God (33:23).

(The Hebrew word here translated as “back” refers to the “hindquarters”—a polite way of saying that Moses saw only God’s exposed buttocks, rather than his smiling face. Almost every translation chooses the polite wording, “my back”. The King James Version comes closest to an honest translation with “my back parts”.)

Yet the request for God’s face to shine upon people is pressed in a number of other psalms. “There are many”, says the psalmist, “who say, ‘O that we might see some good! Let the light of your face shine on us, O LORD!’” (Ps 4:6). In Psalm 31, the psalmist sings, “Let your face shine upon your servant; save me in your steadfast love” (Ps 31:16). Again in Psalm 67, the psalmist echoes more,explicitly the Aaronic Blessing, praying, “May God be gracious to us and bless us and make his face to shine upon us—Selah—that your way may be known upon earth, your saving power among all nations” (Ps 67:1–3).

In the seventeenth section of the longest of all psalms, Psalm 119, a prayer asking for God to help the psalmist keep the Law culminates with the request for God’s face to shine: “Turn to me and be gracious to me, as is your custom toward those who love your name. Keep my steps steady according to your promise, and never let iniquity have dominion over me. Redeem me from human oppression, that I may keep your precepts. Make your face shine upon your servant, and teach me your statutes.” (Ps 119:132–135).

Another psalm indicates that human faces can shine: “you [God] cause the grass to grow for the cattle, and plants for people to use, to bring forth food from the earth, and wine to gladden the human heart, oil to make the face shine, and bread to strengthen the human heart” (Ps 104:14–15). The Preacher, Qohelet, links a shining human face with Sophia, Wisdom. In response to the question, “who is like the wise man? and who knows the interpretation of a thing?”, the Preacher proposes: “Wisdom makes one’s face shine, and the hardness of one’s countenance is changed” (Eccles 8:1). A shining face is a sign of being imbued with Wisdom!

This idea is then picked up in apocalyptic writings, such as 2 Esdras, writing about “the sixth order, when it is shown them how their face is to shine like the sun, and how they are to be made like the light of the stars, being incorruptible from then on” (2 Esd 7:97). In a later chapter, as Ezra encounters a weeping woman, he reports, “While I was talking to her, her face suddenly began to shine exceedingly; her countenance flashed like lightning, so that I was too frightened to approach her, and my heart was terrified” (2 Esd 10:25).

The trajectory flows on into the New Testament, as Paul in writes to the believers in Corinth, applying the language of a shining face to Jesus: “it is the God who said, “Let light shine out of darkness,” who has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2 Cor 4:6).

The culmination of this trajectory is reached in the accounts of the Transfiguration of Jesus, on a mountain, when Jesus was transfigured (Mark 9:2), “the appearance of his face changed” (Luke 9:29), and “his face shone like the sun” (Matt 17:2). And so, the brightly shining face of Jesus, God’s chosen one, points to the enduring steadfast love and covenant faithfulness of God, which is what is remembered and celebrated with such clarity each Christmas.

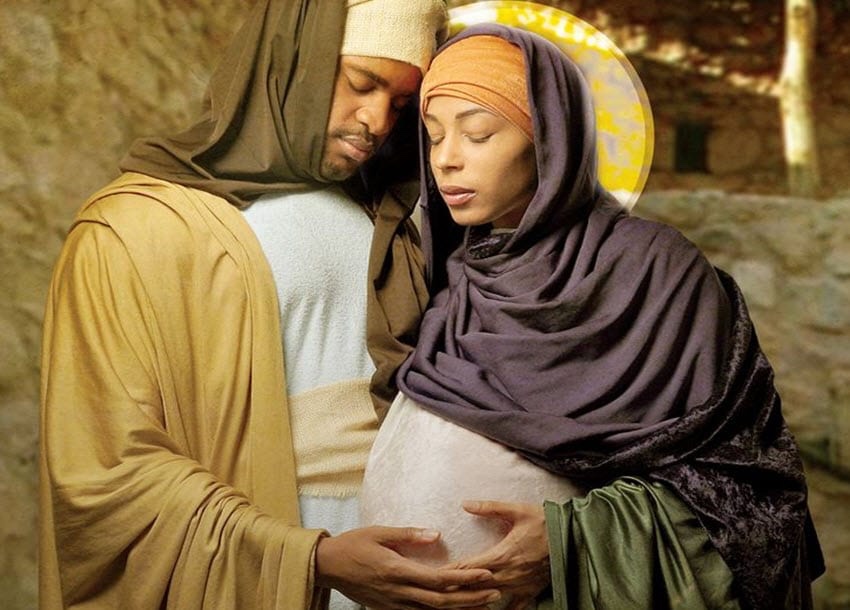

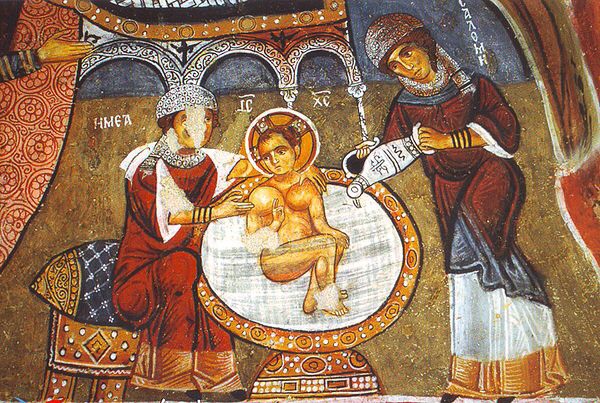

And so it is that these verses from Psalm 80 stand on the fourth Sunday in Advent as a pointer to the coming Christmas celebrations. (And the divine glow, of course, is there to see in so many of the classic Christmas images that adorn Christmas cards and shop windows!)