Every year, for as long as I can remember, around this time of the year, there are media stories that report the honours that are being bestowed upon citizens in our society.

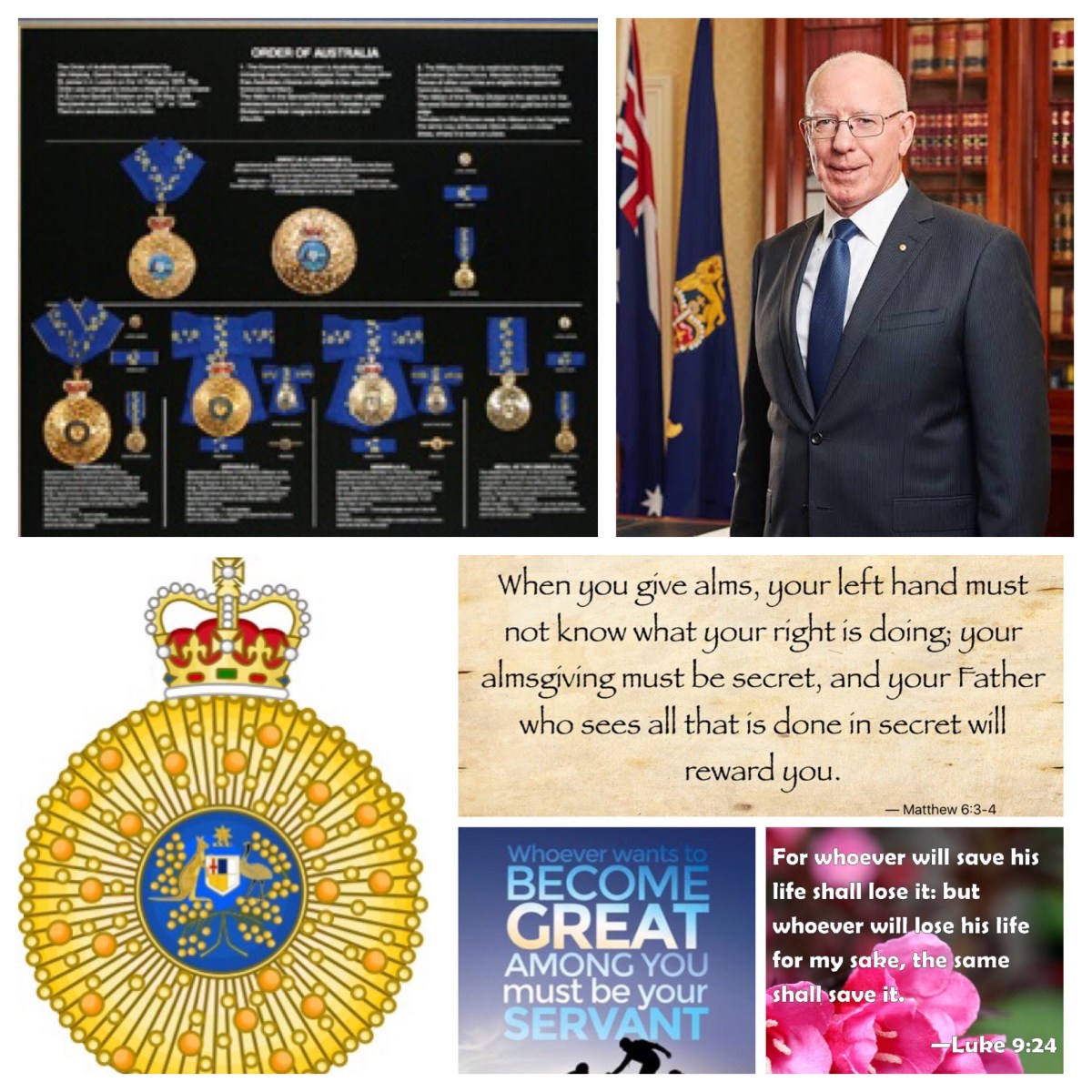

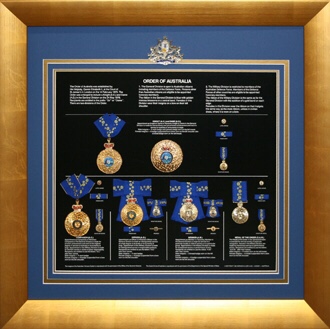

Every Australia Day in January (as well as every Queen’s Birthday in June), a long list of names is published, honouring lots of people. The awards are categorised under various levels in the Order of Australia: Companions (AC), Officers (AO), Members (AM), as well as a list of people awarded a Medal (OAM). There are both Civil and Military sections in each of these levels.

The reasons identified for the various honours given are identified by various activities undertaken by the recipients. This can include “service to the community” in philanthropic and other worthwhile ventures, often in voluntary capacities with charities, religious groups, community organisations, and the like. These awards say something like “we appreciate that you gave your time, energy, expertise” to this good cause, usually over an extended period of many years, even decades.

I’ve got no complaint about such recognitions being made. Indeed, this seems to fit very well with the stated aim of the awards system, to honour “Australians who have demonstrated outstanding service or exceptional achievement” (see https://www.gg.gov.au/australian-honours-and-awards/order-australia)

There is also “service to the community” through the various professional sectors of society—basically, awards which say “you did a good job in the work that you were paid to do over these many years”. That’s a different kind of recognition. Surely, if a person is paid to do their job, and they do it well, even very well, then their employer should recognise and celebrate this—and perhaps even hold an event to make this acknowledgement more public than just within the in-house of employment?

It is instructive to read the reasons for the upper levels of awards given. Here’s a sampling from the AC and AO awards issued in June 2020. First, there is “For eminent service to the people and Parliament of Australia, particularly as Prime Minister, and through significant contributions to trade, border control, and to the Indigenous community” (yes, that was Tony Abbott); “For distinguished service to the people and Parliament of New South Wales, particularly as Premier, and to the community” (Mike Baird, in NSW); “For distinguished service to the Parliament of Australia, to the people of New South Wales, and to women in politics” (Bronwyn Bishop, NSW Senator); “For distinguished service to the Parliament of Australia, to the people of Queensland, and to fisheries research and development” (Ron Boswell, Qld Senator). Enough said.

After all these political personages, there follows awards for “distinguished service to business in the energy, gas and oil production and infrastructure sectors … to aerospace and mechanical engineering, to education and research … to business, particularly through a range of travel industries, to professional tourism organisations … to public administration, and to international legal practice, through senior counsel and advisory roles … to higher education, particularly in the field of economics and public policy, and to professional societies.”

So that’s one way to analyse the awards. The higher awards go to politicians and people at the peak of their respective professional fields. All for doing their jobs well. Occasionally the phrase “and for community service” sneaks in, but not often. So it’s really about awarding the privileged and powerful who have “made it”.

They have “made it” by the hard slog of winning lots of elections, or by the hard slog of doing their demanding job really well. We could well debate whether we need this whole complex system to pat on the back those who’ve already received accolades, the trappings of office, the height of their professional work, for this hard slog.

There’s another way to looks at all of this. That’s an analysis that our own Governor General, David Hurley (pictured below), has offered this year.

As the person responsible for overseeing this whole process, he has noted some very striking biases. Such as:

The higher awards – the Companion of the Order of Australia and the Officer of the Order of Australia – tend to go to the rich, male and powerful. About 130 directors of boards of ASX 300 companies are members of the Order of Australia, and the suburbs in which AC and AO members are most likely to live are Toorak in Melbourne and Mosman in Sydney, followed by Melbourne’s South Yarra and Kew, and Sydney’s exclusive Vaucluse.

No one in the “Multicultural” or “Disabled” fields of endeavour have been made members of the AC, but the “Parliament and Politics” category has 42 ACs, while “Business and Commerce” leaders have 48 of them.

And indigenous Australians are completely under-represented in the honours system. In fact, there has not even been an indigenous member of the Council for the Order of Australia for almost a decade, now.

That’s an extraordinary admission by the very person charged with overseeing the system—a clear, public recognition that (as he wrote recently to the various peak bodies who need to bring recommendations), “quite candidly, ‘I don’t think you’re doing well enough.’ ”

It’s a system for rich, white, privileged blokes — rich, white, privileged blokes, who reward other rich, white, privileged blokes — and who sometimes let others squeak in, just a little, but not at the upper level, no thank you, just at the lower levels of recognition.

It’s a system that is completely inappropriate for the current context. It’s a system that needs to end. And there is already one extremely high-profile award in this year’s Australia Day honours that has highlighted, once again, the embedded inequities, biases, and discrimination that is at the heart of a system that rewards a person for things that are so far removed from recognising “Australians who have demonstrated outstanding service or exceptional achievement”.

So here’s the deal: what if all those “little people” who are nominated for an award, actually say, “thank you, but no thanks”. What if all the folks who genuinely merit such recognition — women, Aborigines, faithful community group leaders, devoted church and charity people, and even philanthropists, and the like — what if they turn it down, and leave only those rich, white, privileged blokes as the recipients?

And wouldn’t it be great if this mass rejection movement was led by all those folks (good, honourable, decent devoted) who are people of faith? After all, the central ethos of following Jesus calls for a focus on servanthood, placing others before self, and not doing things for show.

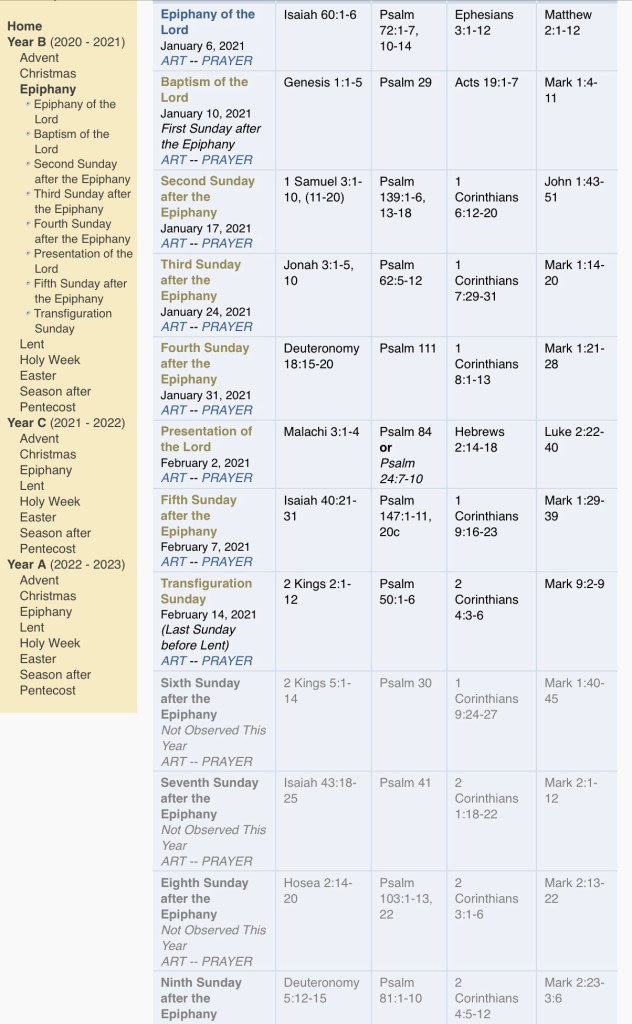

So wouldn’t it be a wonderful testimony to our faith, if the move not to accept an honours nomination would be led by those who live by the guide, “whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be slave of all” (Mark 10:43-44)?

Who adhere to the instruction, “whenever you give alms, do not sound a trumpet before you, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, so that they may be praised by others … when you give alms, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your alms may be done in secret” (Matt 6:2-4)?

Who pattern their whole lives on the word that “those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will save it” (Luke 9:24)?

Such a wholesale mass repudiation of the honours system would expose that system for what it is. And would hopefully drive us closer to closing down this biased, anachronistic, self-congratulatory system once and for all.

*****

Update on 27 Jan 2021: see https://www.theage.com.au/national/faith-rattled-in-australia-day-honours-20210127-p56x9m.html?fbclid=IwAR30XdhVn9MeWGuj3eSxwZC1LcaZB2Uv7ooKFhjLc0e73XGVi1Mm_V3l2rs