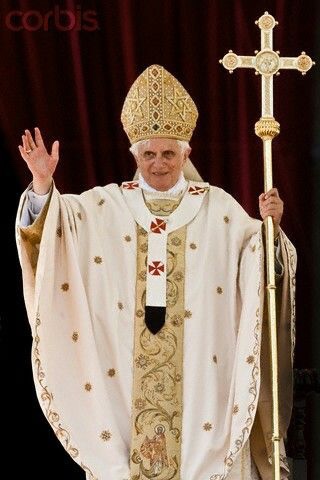

The following Obituary for the recently-deceased Pope Benedict XVI was written by Noel Debien, a theologically-astute, practically-involved, faithful practising Roman Catholic Christian, who works as a Religion and Ethics Specialist for the ABC.

As a Protestant, I don’t share the same understanding of Roman Catholicism or hold to the same perspective on the Pope that Noel demonstrates in what he has written. It seems to me that the late Pope Emeritus was a complex character, in a difficult leadership role, in a larger, diverse, unwieldy institution that (like all churches, and all organisations) was facing multiple challenges, to which it responded in various ways, both helpful and unhelpful, both constructive and reactive.

But what Noel writes is worth our reading and our consideration. I do appreciate the clear insights and thoughtful analysis that he offers in this piece, and am sharing this with his permission. I think that this piece would merit its own nihil obstat as a good explanatory piece to those of us outside Roman Catholicism 😁

OBITUARY: Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger

Born: 16/4/27 Marktl am Inn, Diocese of Passau, Germany

Benedict XVI (19/04/2005–28/02/2013)

He was the first pope to step down in 600 years.

He had chosen his papal name to honour both Pope Benedict XV who led the church through World War I, and St Benedict of Nursia, European monastic leader. He said the name Benedict reminds us “to hold firm Christ’s central position in our lives”. He was deeply critical of the European union when, in its 2008 50th anniversary it failed to include Europe’s Christian heritage in its declaration.

The same pope Benedict XVI canonised our first Australian saint, Mary MacKillop in 2010. During his 2008 World Youth Day visit to Australia he reached millions, establishing him firmly in Australian awareness. He also consecrated the new permanent altar of St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney. It was also during this visit that he made more world news with his first public apology to victims of child sex abuse by Catholic priests and religious. Over 4,444 survivors in Australia from Catholic religious leaders alone. Many more from other religious institutions.

He said his 8-year long pontificate was all about ensuring continuity and avoiding disruption. This was indeed a “continuity” with his predecessor John-Paul II. He was a traditionalist, yet his resignation and retirement marked him as a genuinely modern pope. A man who was generally averse to “novelty” ended up establishing that the retirement of modern popes is normal. He chose to serve as pope only while his health allowed.

As a smoker, he’d had an embolism in the eye in 1984, recovered from a stroke in 1991 – and was eventually completely blind in his left eye. While he was accused of “secularising” the papacy by stepping down “as if someone in public office”, he firmly rejected this allegation. He remarked that “Even a father’s role stops… he does not stop being a father, but he is relieved of concrete responsibility”. After he retired, he decided to be known as “Pope Emeritus”.

On clerical sexual abuse, he was relatively decisive. His interpretation of the abuse crisis was also “outside the usual model” of church response, as something that came from the outside secular culture. In a “culture war” perspective, he included the views of the broader world, not just internal church views.

More bishops were required to resign under Benedict than any previous pope. One of his first actions was to accelerate the investigation into Fr Maciel Degolado. Degolado, founder and head of the Legionaries of Christ was a drug-addicted sexual predator. Pope John Paul II had refused to believe horrendous allegations about Degolado, and even as this previous pope lay dying, the future Benedict XVI was already moving on Degolado. Still, critics point out that despite Benedict’s determination, Degolado was never arrested and charged.

As a 35 year-old professor of theology, Joseph Ratzinger participated in the 2nd Vatican Council. He was actively there, and lived right through it. He helped German Cardinal Josef Frings prepare for it. He accompanied Frings to the council as a “peritus” (expert). Along with famous names like Yves Congar, Hans Urs Von Balthasar, Jean Daniélou and Henri de Lubac, Ratzinger was deeply engaged in that momentous church reform. But his criticism of Vatican II started already when he took distance (like Rahner and de Lubac) from the theology of GAUDIUM ET SPES. He became Archbishop of Munich-Freising in 1977 at age 50, and a Cardinal in the same year.

Born in 1927, Benedict was the longest-lived person ever to have been pope. As pope, he was an absolute monarch, yet he had also known starvation during World war II. His family were anti-Nazi. His own 14 year old cousin (with Downs syndrome) had been murdered by the Nazis in 1941 in their “eugenics” program. He spent time as a reluctant German soldier (he deserted!), and then as a prisoner of war in a US camp at Ulm. He resumed his studies for priesthood as soon as World War II ended. This was in the midst of a devastated Germany.

Over his long life, he observed the repression of Christianity in China, the Cold War, the Cuban Missile crisis, man on the moon, the collapse of Soviet Communism and the American sub-prime mortgage crisis . He also presided over the increasingly shocking clerical sexual abuse crisis that brought large parts of his church to its knees.

He did try to deal with interfaith relations, and had some success, but the relative disaster of the speech he made in Regensburg on Islam (September 2006) was not particularly helpful for his overall record. His words sparked international controversy (to be fair, he accurately quoted the besieged Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos) “Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached”.

from the central balcony of St Peter’s Basilica, at the Vatican,

after his election as Pope in April 2005

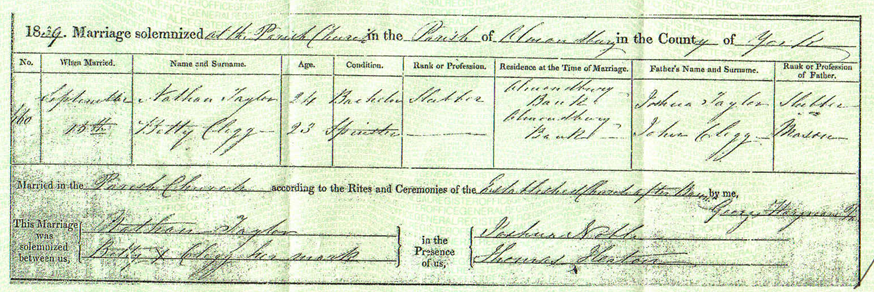

German Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger had been elected pope on April 19th, 2005 at the age of 78. He said this was to his great surprise. “The falling of the guillotine” he called it. But it was his later decision to step down from the papacy at age 85 that helped define the type of active leadership he offered. He had seen his predecessor’s shocking mental and physical decline right to the end, and determined he himself would never die slowly and dramatically in office while leaving others to govern. As the conservative he was, he emphasised precedent from previous resignations of popes.

His theological contribution was immense – especially throughout Vatican Council II. He was a genuine intellectual. At age 39, he became the chair for dogmatic theology at the University of Tübingen in 1966. He wrote and spoke German, French and Latin fluently- so much so that he preferred Latin to Italian- a language he was less comfortable in academically. While describing himself as “shy” and “less emotional”, he was deeply influenced by the intellectual rigour, spiritual teaching and emotional struggle of Augustine of Hippo, the 4th Century North African Bishop and Doctor of the Church. He was a genuine “Augustinian”, who told of his wish to move past classical Thomism, the foundational Catholic theological contribution of St Thomas Aquinas. Thomism had been criticised as “frozen” and “manual-bound”.

Among many other things, St Augustine of Hippo defined “original sin” as Christian doctrine. Baptism was required to cleanse this world-sin though God’s gift of grace. Pope Benedict was deeply conscious of this original sin-of-the-world, and deeply cautious that human passions ought to be ordered and managed. His answer was doctrinal purity and adherence to Christian teaching. His experience of Nazi Germany and its post-war destruction left him in no doubt of the consequences of the “ways of the world”. By strategic appointments, he re-structured the worldwide membership of Catholic bishops to reflect his own views, and this can be seen (for example) among the conservative majority among the current members of the American Episcopal conference.

The “Vati-leaks” scandal that began in 2012 did nothing to allay Pope Benedict’s mistrust of “the world”. His own personal butler, Paolo Gabriele, later admitted (and was convicted) of stealing documents from within the papal household and leaking them. Those documents revealed Vatican intrigue, corruption and in-fighting. Pope Benedict was deeply distressed by this betrayal from one so trusted. He remarked the events “brought sadness in my heart”. It is impossible to know how seriously this personal betrayal affected him, but it is true that he resigned just a year later.

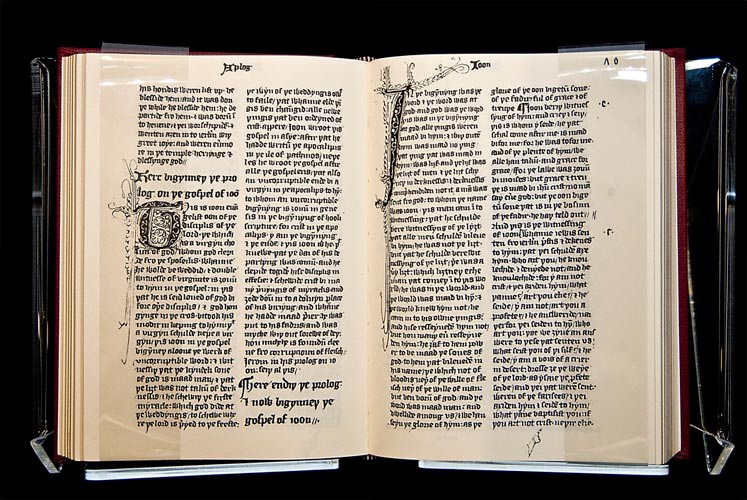

He drove forward many corrections of undesired Vatican Council II outcomes, including (with the help of Cardinal George Pell) a retranslation of the Roman Missal (the church’s key prayer book). Particularly in the English translation, its language was made much more literal to the Latin original – and correspondingly less English in idiom. German Catholics had rejected similar reforms, but they were nevertheless carried out for other language groups including English.

The English retranslations were controversial, and reflected his conservative approach. In January 2009, he had lifted the previous excommunication for renegade “Latin Mass” (“Tridentine”) bishops, one of them a Holocaust denier. It was not a particularly helpful moment for the wider church.

He also re-introduced the old Latin Tridentine rite of mass, the one he celebrated as a young priest. It had been banned by Pope Paul VI in an attempt to modernise worship. He liberalized the use of the Latin Mass in the pre-Vatican II rite alongside the existing one in the vernacular, and in this way he boosted the neo-traditionalist movement against Vatican II especially in the English-speaking world.

Benedict characterised his papacy by stressing “continuity”. He determined that the church in his time should be continuous with the church before the Second Vatican Council, and not ruptured from it. The Liturgy was one of his great loves, and in particular the Mass. Among others, his election as pope delighted traditional Catholic liturgists and musicians around the world. Progressives, and many Catholic bishops not ideologically labelled, were less enthusiastic. He once remarked that the reason he knew Pope John Paul II so well was not through his books, but by observing him celebrate the Eucharist. John Paul II was widely regarded as a mystic, and Josef Ratzinger was attuned to this.

Usually a bit tedious to read, Papal Encyclicals changed. These Papal letters to the world became masterful under Benedict. “CARITAS IN VERITATE” (on global development and progress towards the common good) was a particular success. His were accessible, clear and moving. Many expressed surprise that such an intellectual could hone language so simply and speak so clearly. Million and millions actually read his encyclicals – in itself a papal triumph of public relations. For a renowned University lecturer and writer of academic tomes, he also knew how to write for the people.

He played keyboard and sang, and he deeply enjoyed music. Although he was modest about his own voice (“pitch” he commented once). He had a deep knowledge and abiding interest in sacred music. Under his pontificate his own Sistine Chapel Choir was improved greatly. He was proud that his priest-brother Georg directed the world-famous “Cathedral Sparrows” choir in Regensburg (Germany)– and went to worship with them whenever he was able. Church musicians around the world took delight in his informed encouragement. However, the shadow of abuse later fell over even his beloved Regensburg Choir school.

As a Cardinal, he had been nicknamed the “Enforcer”. This was during his time heading the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith” (once known as the “Inquisition”). He was a man of rules. The career of many a Catholic theologian ended under his supervision. He was key to the deeply controversial teaching document “Dominus Jesus” in the year 2000. Critics described it as a ‘Public Relations Disaster’ for Ecumenism because it made clear that his Vatican did not consider Protestant churches to be authentic churches, yet supporters of “DOMINUS JESUS” praised it for its Catholic “clarity”. Overall, his was not a particularly ecumenical career, especially in terms of Protestant churches.

In 2009, he alarmed many Anglicans when he created an “Anglican Ordinariate”, designed to receive disaffected Anglicans into the Catholic church while keeping many of their own traditions. It had limited success, receiving many clergy who objected to the ordination of women. Nevertheless, his state visit to the United Kingdom one year later, the first such UK state visit of a Roman Pontiff, was hugely successful. During that visit he beatified the former Anglican Divine (and convert), Blessed John Henry Newman.

As a Cardinal he was also central in the drafting of the Catholic Catechism of 1992 – the worldwide standard source for Catholic teaching. Concerning his enforcer role, he saw it as “service”, and was satisfied someone had to admonish and to warn the church. He was not afraid of unpopularity, and there was a contrarian spirit in him typical of an academic more than a pastor. But his enforcement was not always decisive in outcome, such as with United States nuns in 2012. Pope Francis ended the investigation into the USA Leadership Conference of Women Religious relatively discreetly in 2015.

As a Cardinal, Joseph Ratzinger was known as the “enforcer”. As Pope and bridge-builder, Benedict XVI was required to be the “unifier”. His was a pontificate of intended continuity, but yet may prove to have been strained by competing factions, both within the church, and by the more general culture wars of the West.

(Noel James Debien, 2 January 2023)